Warwick Thornton: Mother Courage

Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne | Until 23 June 2013

A WHITE Toyota HiAce van encrusted with orange dust is parked askew in a darkened gallery beneath Federation Square in Melbourne. An older Aboriginal woman, decisively planting daubs of paint on a canvas, is visible in the front cab, a round-faced teenage boy nonchalantly eating Cheezels beside her. The woman is the contemporary equivalent of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage; she’s driven out of central Australia and is now painting for her life as she travels from biennale to biennale, exhibiting and selling her wares – a little like this installation, which premiered at dOCUMENTA (13) at Kassel, Germany, in 2012, before opening at ACMI, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, in early February.

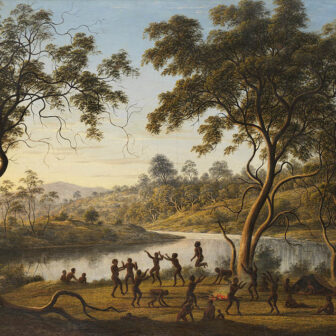

The vehicle’s back door has been flung open to reveal footage of the pair shot front-on, the flipside of the reel in the cab. Together, the films play on a continuous loop, as if to suggest both the repetitiveness of their lives and the durability of the older woman as she struggles to support herself, her grandson and who knows how many others. Trappings of itinerant remote community life are scattered about the van: a string bag, oil paints, a crocheted rug for a seat cover, country and western CDs and cassettes. Canvases are draped over its sides, as if for sale. A pair of large panels in styles using ceremonial body-paint markings made familiar by Atnwengerrp painter M. Pwerle features on one side. On the other is a series of naïf-style pictures revealing scenes from community life: some idyllic, some not so, including one of a community with signs warning “no grog, no pornography, no wepons [sic]... no jobs” – an ironic twist on signs mandated by the NT Intervention – and one with what look like black tombstones labelled with different types of grog looming out of an orange and purple landscape. All the while, the Green Bush program from an Aboriginal community radio station plays on an old ghetto blaster in the background, providing the film’s narrative arc: You’re listening to the Green Bush radio [show]. If you’ve got a message you’d like to send out to friends and family in prison…

The program’s prison audience offers a portent of a possible future for the boy, if he follows the all-too familiar rite-of-passage for many Aboriginal male youths into custody. The radio grabs are from Thornton’s earlier short film, Green Bush (2005), based on his experiences as the DJ on an Aboriginal community radio station, communicating through song selections between those on the inside and the outside. They recall the opening scenes from his feature, Samson and Delilah (2009), in which the young male protagonist wakes up and sniffs petrol listening to the same program. This reference might seem too negative an omen for the young man, but shoved behind the van’s windscreen are two newspaper articles that suggest alternative paths for him: a good news story about the local land council’s ranger programs alongside a tabloid one about the incarceration of youths at risk.

The survivalist grandmother who holds her family together and the potentially at-risk young man are familiar types from Aboriginal community life. In a recent radio interview on Awaye!, Thornton expressed concerns about the potential disintegration of community life with the passing of the current generation of grannies, especially given their dual role as repositories of culture and nurturers of a generation whose parents are often absent because of addiction or incarceration. This tension is present in the emblems of ongoing attachment to country and culture, alongside those of basic survival, that deck the installation: a red palm print, an Aboriginal flag sticker, the canvases on the van’s sides, the ininti-seed necklaces hanging from the rear vision mirrors, and Mother Courage herself, using a traditional creative practice to survive. Nevertheless, there’s a grimness about her assertion of cultural identity that recalls Delilah’s fate when she returns to live on country as the teenage partner of a sniffer in a wheelchair.

Some of Thornton’s work has been criticised for its focus on contemporary social dysfunction. Samson and Delilah, for example, portrayed two teenagers’ experiences of rejection and isolation in a remote community and in Alice Springs through a series of events that are perhaps unlikely within the timeframe in which they occur. This compression of incidents from Aboriginal everyday life also features in Green Bush, and Thornton has explained in interviews that all the material in his films is drawn from his own experience. While his films are ostensibly realistic, their dense and highly emblematic use of everyday objects and incidents prefaces an understandable transition from film-making to art installation. Thornton debuted his first installation, Stranded, at the Adelaide film festival in 2011, and elsewhere he has commented on the appeal of the relative immediacy of an art installation project compared to the often expensive and lengthy process of film-making.

It is as if through his recent creative works Thornton seeks to expand his former role in Aboriginal community radio by exposing national and international audiences to central Australian Aboriginal life events they are otherwise unlikely to encounter. At the same time, these experiences – the haircutting episode and the return to country on the outstation in Samson and Delilah, for example – are often presented without much explanation. Much extra-textual material (in a brochure, on a plaque) accompanies the ACMI installation, providing back-story details not apparent in the work. There, we learn that Mother Courage left her community after its art centre closed down for lack of funding, and because of pressures accompanying the Intervention and increases in the price of fuel, power and water.

The end of the installation’s film coincides with Green Bush’s final announcement: And that’s it for the Green Bush tonight. There’s also another night and another night. Because when you think about it, you mob, you’ve been a captive audience for a long time. But who exactly is the captive audience? Mother Courage is potentially as enigmatic for the gallery visitor as the sight of Aboriginal ladies dot-painting canvases on public lawns is for tourists in Alice Springs. The pair in the van exude a strong sense of self-containment as they sit focused intently on the canvas. Very little is said, apart from the woman’s instructions to her grandson, and when the two of them occasionally look up, it’s not to make eye contact with the viewer or the cinematographer but as if to observe some activity outside the frame.

Mother Courage evokes both the immediacy and proximity, and the distance and impenetrability, of remote Aboriginal experience for the non-Aboriginal urban viewer. It also contrasts the basic circumstances of many Aboriginal creative producers with the largesse of the international art world, on whose gallery walls some of their artworks hang.