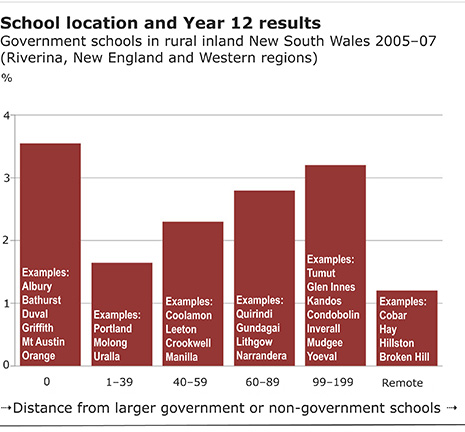

RECENT NEW SOUTH WALES Board of Studies statistics reveal some very interesting things about schools and school performance in rural and regional parts of that state – findings that help illuminate the potential impact of national policy trends. The chart below, which appeared in my earlier article for Inside Story, Gone Bush, shows how the average Higher School Certificate scores of rural schools in three NSW regions increase the further they are located away from larger centres and larger competing schools. The scores for schools much closer to larger towns and competing schools are less impressive, as are the profile of schools in very remote locations. But highest of all are the schools in the largest towns. (In both charts in this article the vertical axis shows the number of HSC marks over 90 as a percentage of exams sat.)

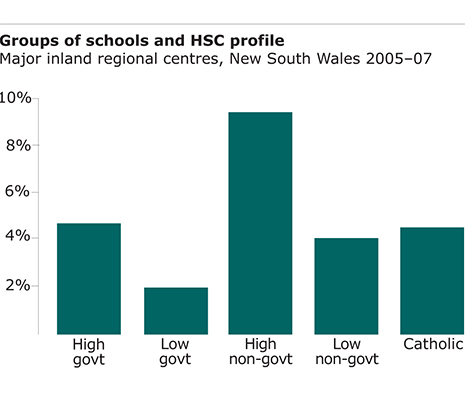

Do these statistics suggest that schools in large centres are all winners? Not at all – another drama is playing out in the larger towns, a drama familiar to city-dwellers across Australia. Each regional centre has up to four private schools with a high academic profile and one or two equivalent public schools. Struggling alongside these are typically a couple of lower academic profile public schools together with those Catholic schools which still attempt to play out their historical mission to serve the poor.

Do these statistics suggest that schools in large centres are all winners? Not at all – another drama is playing out in the larger towns, a drama familiar to city-dwellers across Australia. Each regional centre has up to four private schools with a high academic profile and one or two equivalent public schools. Struggling alongside these are typically a couple of lower academic profile public schools together with those Catholic schools which still attempt to play out their historical mission to serve the poor.

In the same way that the large centres have cannibalised the countryside, within the large centres schools compete to harvest preferred students. Among government schools this competition is constrained by regulation, particularly in the form of what are called “drawing areas” in New South Wales. As a result, the schools with that can be choosiest about who they enrol are the private schools, which absorb talented students whose families can afford and are prepared to pay school fees.

When you combine the HSC profile of these different groups of schools the hierarchies they form become very obvious, as indicated on the chart below. Some might argue that this division between types of schools simply shows that private schools deliver better results. Yet research in Australia and overseas consistently shows that the ownership of a school – public or private – has little if any influence on the results achieved by students. Certainly the student test scores vary considerably between schools, but most research properly takes in account such factors as socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender, disability, English proficiency, school location and resources.

In one sense there is little about the developing hierarchies of schools in these big towns that is unique. It is happening all over Australia – it is just easier to see in the bush. Some of this is inevitable: even large country towns have income and other social divides between suburbs or localities. But the growth of private schooling creates yet another layer: when fee-charging schools operate alongside free schools (which must be inclusive), the enrolment profiles of the schools start to look quite different. The existence of these fees, combined with a number of other choice mechanisms and school practices, ensures that the enrolment in the private schools is skewed towards higher income and aspirant families.

In one sense there is little about the developing hierarchies of schools in these big towns that is unique. It is happening all over Australia – it is just easier to see in the bush. Some of this is inevitable: even large country towns have income and other social divides between suburbs or localities. But the growth of private schooling creates yet another layer: when fee-charging schools operate alongside free schools (which must be inclusive), the enrolment profiles of the schools start to look quite different. The existence of these fees, combined with a number of other choice mechanisms and school practices, ensures that the enrolment in the private schools is skewed towards higher income and aspirant families.

When combined with the layer of religion this is dividing up large country towns in ways which are new and, to many people, very disturbing. Across Australia 40 per cent of enrolments in public secondary schools are low income families; the equivalent figure for private secondary schools is not much more than 20 per cent. While public schools enrol 67 per cent of all children across Australia they have almost 80 per cent of at-risk students. Schooling in the big towns increasingly reflects such patterns, as well as racial divides. Aboriginal students make up twenty-five per cent of the enrolment of the state secondary college in Dubbo; the equivalent figure for the biggest private school in the city is much less than five per cent. It is now possible to identify the marginalised schools in so many of our large towns. The blame doesn’t necessarily belong with individual schools or even school authorities. It is just yet another awful by-product of the way we have set up public and private schools in this country.

In the scramble to retain a reasonable spread of enrolments even some of the public schools in the larger towns have turned on each other. In towns such as Griffith, Wagga and Albury preferred enrolments gravitate to some schools at the expense of others, regardless of enrolment catchments. In the process some schools have grown and others shrunk to the point of catering for the relatively disadvantaged.

Examples abound. In Albury, Wagga, Queanbeyan, Orange and Tamworth the biggest government high schools are up to twice as big as the smallest, sometimes more. Like many schools in Sydney, Karabar High in Queanbeyan offers a gifted and talented program. It’s a double-edged sword: what some people see as provision of a wonderful opportunity others see as a thinly veiled attempt to poach top students, with others almost certainly following. The NSW government, having generally compounded the problem with 28 full or partly selective schools, is soon to drop selective classes into Armidale and Grafton as well. While all the public high schools in those two cities will get selective classes, they will inevitably draw in more students from the schools in towns nearby – as well, it should be said, from the private schools. None of this is about healthy competition; none of it makes schools any better.

The schools which lose the vital resource of aspiring and engaged students and families, who lose their high-achieving role models, end up serving an increasingly marginalised group of strugglers and the disengaged. Across Australia this has made the problem of lifting up the bottom – so essential to productivity and community-building – much harder to achieve. Increasingly there is no one at school for the strugglers to look to in order to see how it is done.

The experience of rural schools and centres challenges, in very visible ways, prevailing free-market beliefs about the value of choice and competition in schooling. Assumptions about the value of competition between schools even emerged in the Rudd dovernment’s first budget and the deputy prime Minister seems firmly committed to publishing more comparisons between schools. The reality is that choice and competition is appropriate to the world of business, but its success in creating quality schools for all is at best very mixed.

Competition has never lifted all schools for the benefit of all. It has a place in the classroom, not least because teachers can help most kids become winners of some kind, and competition between schools might even improve some aspects of their operation. But in this competition, some schools are starting well behind the starting blocks. The ones which lose out don’t have to be the worst or even bad – they just can’t compete as easily on a playing field which is tilted against them and their kids. This sort of competition just lifts their most achieving kids out of their classrooms and places them in what parents see as more advantaged schools and circumstances. This is not about blaming parents – it is just what happens.

Competition has one impact on learning. It has quickly taught schools and principals a golden rule of business: the quality of the product – and the reputation of the producer – is enhanced if there is greater control over the inputs. In the case of schools the most important inputs walk in through the school gates each day, carrying bags, benefits and baggage. The schools which best position themselves to pick the best, get the best – and are better able to claim a spot at the top of the ladder.

These patterns might continue to change into the future. The costs of commuting to school as well as work are mounting. In New South Wales the subsidisation of student travel to school has reached the half billion dollar mark and will eventually prove unsustainable. Growth patterns in rural areas can always shift as the economic base of towns continues to evolve. Patterns of schooling can also change, especially as online learning takes hold. Perhaps one day we might decide that we can and should offer comparable opportunities to students wherever they are located and whatever their circumstances of birth. Perhaps we’ll eventually notice that the evidence is increasingly showing that successful education systems are those which value equity, along with related ingredients such as quality teachers for every student. •