Managing the Undesirables

By Michel Agier | Polity | $37.95

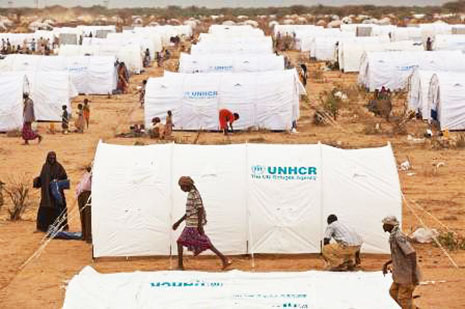

FOR regular viewers of international news bulletins, the mention of refugees is likely to conjure up two sets of images. One shows the vast expanse of the Dadaab refugee camps in northern Kenya, with rows of white tents stretching away to the horizon. At present, the camps have a combined population of more than 440,000, with about 1200 more refugees – mostly Somalis fleeing famine and conflict – arriving every day. A couple of weeks ago, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees was urgently seeking another 45,000 tents to accommodate the influx.

The other set of images shows “boat people” arriving on the Italian island of Lampedusa and on Christmas Island. Both are outposts of the privileged part of our world: Lampedusa is geographically much closer to Africa than to Europe, and Christmas Island is more than five times closer to Jakarta than to the nearest Australian capital city, Perth. Since the beginning of 2011, just over 2000 “boat people” have arrived in Australia. Over the same period the number reaching Italy – and in most cases that means Lampedusa – has exceeded 50,000.

In Australia, politicians, journalists and many of those who vent their spleen on talkback radio have characterised the arrival of that tiny number of asylum seekers – less than 0.01 per cent of the Australian population – as a crisis. Italian commentators are perhaps more justified in describing the arrival of tens of thousands of refugees from North Africa – mostly people fleeing Libya – as an emergency, but even those numbers should be seen in perspective. Since the beginning of the uprising against the Gaddafi regime about a million people have fled, but it is Libya’s neighbours, rather than European countries, that have dealt with most of those refugees. Between them, Tunisia and Egypt have accommodated more than 900,000 people crossing their borders. While this year’s boat arrivals in Italy amount to less than 0.1 per cent of that country’s population, the number of refugees entering Tunisia from Libya was in excess of 5 per cent of the Tunisian population.

Governments in Europe and Australia have taken drastic measures to respond to crises reputedly brought about by the arrival of asylum seekers and other irregular migrants. The government of Julia Gillard has struck a deal with its Malaysian counterpart to save Australia from responding to protection claims. Barring an adverse decision by Australia’s High Court, the deal would allow the government to deport 800 asylum seekers arriving in Australia – including children and unaccompanied minors – to Malaysia, which is not a signatory to the UN Refugee Convention and has a dubious human rights record, particularly in relation to the treatment of irregular migrants.

In Europe, France and Denmark reintroduced border controls and effectively suspended the Schengen Accord, which guarantees passport-free travel among twenty-five European countries with a combined population of more than 400 million. In an attempt to offload refugees from northern Africa, the Italian government issued travel documents to boat arrivals that allow them to move on to other European countries.

When the term “crisis” is applied to the arrival of boat people in Italy or Australia, it refers to the impact of the unauthorised movement of people on those who might be compelled to accommodate them. What is currently happening in the famine-ravaged countries of the Horn of Africa, is also variously termed a “crisis,” an “emergency” or a “humanitarian disaster.” But there, the crisis is clearly being endured by those whose very lives are threatened by famine and conflict.

In Australia, the sense of crisis about boat arrivals can’t easily be justified by televised footage of small groups of asylum seekers disembarking from rickety boats under the watchful eyes of the Australian Federal Police. Instead, it’s the mere mention of unauthorised people entering Australia from countries to the north that reawakens fears of an invasion. The Australian imagination does not rely on actual images to run wild. In Europe, the sense of crisis is generated by media images of overcrowded boats carrying African refugees and hundreds of refugees milling at the wharf in Lampedusa after their disembarkation. Those images provide a highly selective snapshot of the situation in Italy and suggest that the authorities are barely coping with the influx of refugees – that, in fact, chaos reigns.

By contrast, the rows upon rows of white tents in Dadaab convey a sense of order. From the viewpoint of the privileged minority in the West, the crisis is being managed. The rows of tents seem to show that the international organisations providing white tarpaulins for such large numbers of people are also capable of delivering water, food and medicine to the inhabitants of those tents – assistance that makes it unnecessary for them to keep moving. But aerial photographs of neat rows of tents can be deceptive; they say little about the situation on the ground.

It is arguable whether the crisis management currently provided by NGOs and the United Nations for those enduring famine in the countries of the Horn of Africa is successful. Reports about people still dying of starvation and about scores of them moving across eastern Africa in search of survival suggest that the crisis has not yet been contained. But those directly affected by it are. It’s partly thanks to the tents provided by humanitarian organisations in Dadaab and elsewhere in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and South America that the “refugee crisis” we experience in Europe and Australia is imagined rather than real. The vast majority of refugees have little choice but to aim for camps in their own or in neighbouring countries, rather than for Europe, North America or Australia.

THE United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR, is currently responsible for more than ten million refugees worldwide, and in excess of fifteen million “internally displaced persons,” or IDPs. To be more precise the UNHCR is responsible for a total of 16,024,620 refugees, “persons in refugee-like situations” and IDPs. That’s 16,022,435 more than the number of asylum seekers who arrived in Australia this year by boat.

There are three main reasons why it is difficult to establish exactly how many of these displaced people live in camps: the United Nations doesn’t publish comprehensive statistics about camp populations; the numbers of displaced people in camps fluctuate; and not all camps are administered by UN agencies and included in their surveys.

A couple of years ago, the UNHCR estimated that about 30 per cent of refugees under its tutelage live in camps. This figure doesn’t include Palestinian refugees, who are the responsibility of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. Just under five million refugees are registered with that agency; of those about 1.5 million live in fifty-nine camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank and Gaza. On the basis of those figures, around 4.5 million refugees live in camps overseen by the two UN refugee agencies. Factoring in also internally displaced persons, and people living in makeshift camps outside the reach of UN agencies, it is probably safe to assume that at least ten million displaced people worldwide live in camps.

Although the UNHCR advocates three “durable solutions” for refugees – repatriation, integration in the country of refuge, and resettlement – none of these options is available to the majority of refugees. They are stuck in permanent limbo, usually without the right to freedom of movement, and often without the right to work. Refugee advocates have referred to the quasi-permanent accommodation of refugees as “warehousing”; according to the US Committee for Refugees, one of the most credible and best resourced refugee advocacy organisations, at the end of 2008 more than eight million refugees had been in camps or settlements for more than ten years.

Some of these camps have existed for decades. Most of the camps for Palestinian refugees, for instance, date back to the late 1940s or early 1950s. The refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, were set up in the mid-1970s for Sahrawis fleeing from Moroccan forces; they now house approximately 90,000 refugees. A large proportion of the Sahrawis and Palestinians living in refugee camps were actually born there. Most Tibetan refugees living in more than thirty settlements in North India and Nepal, which were established following the Tibetan exodus in 1959, were also born in exile. And there are many other protracted refugee situations around the world: for example, many of the Tamil refugees in the south of India arrived between 1983 and 1987; some of the Karen refugees in Thailand arrived in the first half of the 1980s; and some of the Angolans in Zambia have been there since they fled at the outbreak of the Angolan civil war in 1975.

In Managing the Undesirables, first published in French in 2008 as Gérer les Indésirables, the French anthropologist Michel Agier observes that “camps are indeed the fourth solution of the UNHCR for resolving the refugee ‘problem’ – a massive and lasting solution, and clearly the preferred one in Africa and Asia, to the detriment of the three other official solutions.” Agier refers to those forced to live in refugee camps for lengthy periods as “undesirables.” They cannot return home, are unwelcome in their countries of refuge, and – a few exceptions aside – are not wanted by countries of resettlement such as Australia.

Agier is director of the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement in Paris. For those accustomed to Anglophone scholarship, the broad-ranging and radical critique of the humanitarian response to forced migration that is advanced by Agier – as well as by his French colleague Didier Fassin, whose most recent book, La Raison Humanitaire, will be published in an English translation later this year – may come as a surprise. Their critique is informed by ethnographic research as well as by the work of philosophers such as, in Agier’s case, Eleni Varikas, Giorgio Agamben and Federica Sossi.

Managing the Undesirables is based on several years of fieldwork in refugee camps in Africa and the West Bank. Agier advances two broad theses, one of them to do with the dynamics of humanitarianism and the other to do with the response of those who are subject to such dynamics.

The first thesis is well argued and convincing, though not particularly original. Agier observes that “humanitarian intervention borders on policing,” since “every policy of assistance is simultaneously an instrument of control over its beneficiaries.” Humanitarian intervention identifies and classifies target populations, and it aims to contain them. The beneficiaries of humanitarian aid are expected to meet fixed criteria that distinguish refugees from “persons in refugee-like situations” and from non-refugees. A more crucial distinction is that between the victim – the person who is deserving of the humanitarian assistance – and the illegal, who is not: “Refugees are adopted by national or international NGOs and UN agencies in the name of human rights, and these take responsibility for them as pure victims, as if they owed their survival simply to the fact of no longer being present in the world, i.e. being de-socialised and in a state of pure biological life – a life that the representatives of the international community decide to extend rather than let it extinguish.” But the distinctions, between different types of refugees and between victims and illegals, often seem arbitrary because the political contexts that produce them have nothing to do with the people who are being categorised.

Agier’s second thesis is more original and far more interesting. Although it is less developed, it makes his book worth reading for anybody interested in the quandaries posed by irregular migration and displacement. Based on his work in the camps (which was facilitated by Médecins Sans Frontières), Agier questions the assumption that those regarded as “victims” lack the ability to shape the social and political context of life in the camp. He suggests that as “spaces of confinement” the camps “are transformed and become, after a certain length of time, sites of a possible public space,” that “dis-placement” can generate “em-placement.” Camps can become towns. Agier writes: “On the ground of humanitarianism, whose action does not attempt to produce a society or found communities but at most to open spaces that are propitious to emergency intervention, a social order of hybrid formation is created; it founds the new locality (in the sense of local identity) of individuals placed collectively in exile here. It is in this new framework, this new social ordering, that inter-ethnic relationships arise, along with cultural apprenticeship, and possibly political conceptions and projects that are specific to such an order.”

Agier identifies and analyses a fundamental tension – between the camps as realms of confinement, controlling people stripped of the rights of citizens, and the camps as spaces of political innovation that favour the creation of new social orders. The latter becomes possible because of the former. That is not to suggest that the productive and creative energies of warehoused refugees somehow redeem humanitarianism. But this tension may serve as a reminder that the response of the privileged minority to refugees tends to be inadequate. That response is primarily emotional: as pure victims, refugees elicit pity; as illegals, they provoke fear and loathing. These emotions, rather than a reflective engagement with the displaced as fellow citizens of the world, underwrite not just the humanitarian effort, but also the response to the very few who successfully evaded their containment and arrive uninvited on Europe’s, Australia’s or North America’s shores. •