In the thaw the knitted garden grew. We buried our jumpers in the ground with a strand protruding above the surface. During the night the lice crawled up the strands so that in the cold morning there were white clumps on the ground like cauliflowers. Stamping on them deloused the jumpers.

HAUNTING images of life in a labour camp fill Herta Müller’s most recent novel, Everything I Possess I Carry with Me. Müller’s inventive use of language makes her work tricky to translate but an English version of the opening chapter is available and a full translation will be published next year. It is a compelling work woven from secrets and suppressed history.

The novel was published in Germany two months before Müller was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in October last year. It is a milestone: where Müller’s earlier works were strongly autobiographical books of prose, poetry and collages using words and pictures, Everything I Possess I Carry with Me works on a broader canvas, covering the full life span of its male protagonist.

Müller was born in a German enclave in rural Romania in 1953. As a child she heard “stolen conversations” about the recent past without understanding anything but the fear they expressed. Eventually she learnt that her mother, along with many others, had been deported to the Soviet Union in 1945 after the Red Army reached Romania and the country’s pro-German fascist leadership was overthrown. Secret Order 7161 of the USSR State Defence Committee demanded that all able-bodied German males aged seventeen to forty-five and all females aged eighteen to thirty would be rounded up to help rebuild the Soviet Union.

The German Romanian deportees were sent to labour camps in the coal-mining regions of the Ukraine. Most were there for five years in dire conditions, and many died. (Müller’s grandmother disclosed that Herta had been named after her mother’s best friend who died of starvation in the camp.) The entire deportation episode was a taboo subject in Romania under the Stalinist Ceausescu regime, spoken about only in whispers.

Müller’s novel brings this suppressed history to life in a bold and unique manner. There are echoes of mass deportations to Auschwitz and Siberia – the deportees are packed into cattle trucks, tyrannised by the camp guards, shaved and reduced to skin and bone – but Müller keeps these echoes to a minimum. The German Romanians were not deported to wholesale death and Müller points to the complicity of the community in supporting Hitler.

She uses a single first-person narrator, Leo Auberg, to describe the deportation and the labour camp with the intensity and singularity of a soliloquy. The seventeen-year-old Auberg was already living a half-hidden life as a homosexual when he was transported into the wholly hidden world of the camp, “outside of time and of ourselves.”

Auberg’s narrative describes the transformation of people into objects. He talks about being subjugated to his shovel: his role is simply to make it operate; he is controlled by the cement and the coal he shovels. “I am an ordinary Russian object,” he thinks as he returns to the barracks at night.

Above all he is the object of hunger. Hunger hovers over him in the form of the “hunger angel,” which torments him but is also a guardian spirit whose presence at least means that he hasn’t filled his stomach by eating sand or cement as some other prisoners do. The hunger angel takes over his existence and quickens his breath. “The hunger angel puts my cheeks on his chin. He makes my breath heave. The in and out of breath is a delirium.”

The German title Atemschaukel – literally, “breath swing” – refers to that strained breathing. Leo contracts this condition in the camp and it never lets him go. He tells his story sixty years after being released from the camp and leaving Romania for Austria, but he still finds that his breath shudders when memories carry him back to the camp. The past is like a poison that is permanently within him. He remains isolated through to the end of the novel and refers in the last sentence to “a sort of distance in me.”

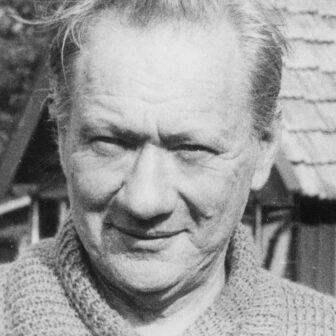

Auberg is based on the German Romanian poet Oskar Pastior, who was one of the deportees. During his time in the camp Pastior put himself at great peril by making notes about life there in a book he assembled out of scraps of cement bags. Pastior and Müller began talking about his experiences in 2001, and in 2004 they visited the remains of the labour complex together. When Pastior died suddenly in 2006 he left Müller with books full of notes, detailed descriptions of camp life and telling images.

In an interview with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung last month Müller talked about how Pastior’s memories welled up in their discussions. “Remembering was a need, an urgency in him,” she said. “The almost monstrous precision of the images of the camp dwelled for years in his head. Finally he could concede that the camp hung on in his head. He really wanted this misery to be described at last.”

BUT THERE was something that Pastior hid from Müller. After being released from the camp he took up studies in Bucharest, where he was denounced for writing seven anti-Soviet poems about the camp and for being homosexual. In 1961, to avoid arrest, he succumbed to the Romanian secret police, the notorious Securitate, and was an informer until his defection in 1968. This fact became known only in September 2010 when Pastior’s secret police file, under the cover name of “Otto Stein,” was identified by a historian.

It’s not surprising that this revelation, eighteen months after the publication of the novel, shocked Müller. The tyranny of repression in Romania and the surveillance carried out by the Securitate are major themes in her work, and she had suffered years of harassment before she and her husband Richard Wagner were permitted to leave for West Berlin in 1987. The news of his collaboration, she told Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, was a “box around the ears.” But after the initial shock, she added, she had realised that if Pastior were still alive she would hug him and encourage him to talk and write about his life as Otto Stein.

The exposure of Pastior’s secret past resonates eerily with Müller’s aim, in Everything I Possess I Carry with Me, of bringing secrets and the suppressed past to the surface. It is a reminder of how the full history of the Soviet labour camps is still being uncovered.

The work of the 1970 Nobel Prize winner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn told the world about the injustices and the appalling conditions in the gulags. We know about the extent of the gulag system and the millions of people subjected to it from histories such as Anne Applebaum’s Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps. Müller focuses on the hidden history of the German Romanians in the labour camps and on the experience of an individual whose experiences there shaped his life. The five years Auberg spent in the camp dominate the rest of his life. Years after his return from the camp he says that his dreams continue to deport him back there. He relives his deportation repeatedly, each repeat scarring him more deeply. He recounts how one night his dreams deported him seven times to the camp and the seventh time is the worst because the camp is abandoned and there is no purpose to his being there. “No one wants me here and I am definitely not permitted to leave.”

Müller’s novel is a compelling narrative that penetrates the anonymity of mass deportation. She brings an unknown past into the open and preserves it. Everything I Possess I Carry with Me is not to be forgotten. •