Politics, as defined by Roget’s Thesaurus: “Manipulation, intrigue, wire-pulling, evasion, rabble-rousing, graft.”

– Sir Humphrey Appleby

THE FIRST episode of Yes Minister was broadcast by the BBC on 25 February 1980. In the thirty years since then – there were three seasons of Yes Minister and two of Yes, Prime Minister – the deeply cynical creation of Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn has taken its place in television history alongside Steptoe and Son, Till Death Us Do Part and Fawlty Towers as one of the very best situation comedies of all time.

What all four programs have in common is that they have no jokes, no gags and no punchlines. They are little dramas, driven by plot and character. When jokes are told they are part of the character’s conversation, not a feeble punchline that excites canned laughter on the soundtrack. Each episode, in its own way, is a little tragedy and we laugh at the pain.

When Paul Eddington was in Australia in 1987 to perform in HMS Pinafore he came into the 3LO studio for an interview. We talked about The Good Life and Yes Minister and about the essential ingredients of a great sitcom. He said that he was not at all impressed with the first script of Yes Minister. He thought it unfunny precisely because there were no obvious jokes, gags and punchlines. He was not optimistic about its chances of success.

In their Yes Minister Miscellany, Jay and Lynn say that Eddington and Hawthorne didn’t agree to take the roles until they had seen the fourth script, because they were worried that they might be tying themselves to a “rubbish” series on the basis of one carefully crafted script. Hmm… that’s not exactly what Eddington told me.

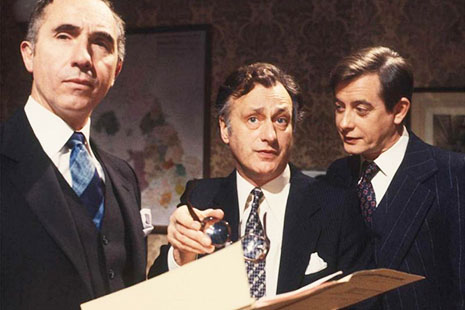

But it could easily have been a dud, were it not for the perfect casting of Eddington as the Rt Hon James Hacker, Nigel Hawthorne as Sir Humphrey Appleby and Derek Fowlds as Bernard Woolley. It is one of history’s great injustices that Eddington never won a BAFTA for his performance as Jim Hacker, minister for administrative affairs and, later, prime minister. Although nominated four times he lost to Hawthorne every time. Perhaps the role of Sir Humphrey is flashier than that of Jim Hacker, but it is Eddington’s remarkable ability to act without saying a word, simply by body language and facial expression, that marks this series as different from all others.

Eddington’s ability to portray disappointment, bewilderment, wounded vanity, duplicity, terror (at the possibility that he might have done something courageous) and sublime bliss (as on those rare occasions when he betters Humphrey – think of when he kisses the post-broadcast tape in which Humphrey is indiscreet about unemployment) by facial expression alone was a constant joy for the audience.

Sir Humphrey: If you want to be really sure that the minister doesn’t accept it you must say the decision is courageous.

Bernard: And that’s worse than controversial?

Sir Humphrey: Controversial only means this will lose you votes, courageous means this will lose you the election.

THE ENDURING greatness of a sitcom is measured by its contribution to the vernacular. Fawlty Towers gave us “Don’t mention the war.” Steptoe gave us “Oh, you dirty old man.” And Till Death Us Do Part left us with “You silly old Moo.” The linguistic legacy of Yes Minister is “Very courageous, minister.” The phrase strikes terror into Jim’s heart every time Humphrey says it and excites the facial acting that made us laugh.

The meta-joke, as it were, of Jay and Lynn’s creation is that it plugs straight into the near-universal contempt for politicians and public servants. Not surprisingly the writers report that “politicians told us that our representation of politicians was somewhat unconvincing and really rather silly but that we had got the civil servants absolutely right. The civil servants, on the other hand, thought our picture of politicians was spot on, though of course our civil servants bore less relationship to reality. The truth was that we portrayed politicians as civil servants saw them and civil servants as politicians saw them. If we had shown them as they saw themselves it would have been the most boring program ever shown on British television.”

But the Yes programs are also about how the electors see their representative as the mendacious, cowardly, self-serving, unprincipled politician, with an eye on the next election. When Humphrey tells us that the politician’s dilemma is that “He must obviously follow his conscience, but he must also know where he’s going. So he can’t follow his conscience, because it may not be going the same way that he is” we laugh because it rings the bell of truth. Or at least the bell of cynicism.

The clever thing that Jay and Lynn did, aided and abetted by two superb actors, was to create characters who are representative of types we despise and then to make us love them as individuals. And in the end we love the politician more than the civil service mandarin. Jim, with all the frailties that political flesh is heir to, is more lovable than the haughty, snobbish, arrogant, unelected wallah who really runs the country. We rejoice when Jim has an occasional triumph, as unexpected in its way as the Coyote ever outwitting the Roadrunner.

Many years ago an American journalist visiting these shores noticed our tendency to political irreverence. In an article for the National Times, published in August 1982, Constance Casey wrote: “Australia is a place where almost everyone I’ve met is extremely funny. At first it was completely enjoyable… Then I began to notice the poisonous effect of continuous self-mockery. I feel as if I’ve arrived at a very isolated, very large boarding school where everyone hates the headmaster and the students feel that they have been sent away by unloving parents.

“The jokes at the masters’ (or politicians’) expense are funny but there’s a sense that once the deflating joke has been cracked, that’s all you need to do.” If Marx were alive today he might very well tell us that political sitcoms are the opiate of the people. For all the brilliance of Jay and Lynn, not to mention Clarke and Dawe and Rob Sitch and the writers of the excellent Canberra sitcom, The Hollowmen, government secrecy makes a mockery of any concept of democracy based on the vote of an informed electorate, but we do nothing about the mockery except mock it.

There is no point in the Cabinet questioning the Treasury. On the rare occasions when the Treasury understands the question the Cabinet does not understand the answers.

– Sir Humphrey Appleby

THE CLEVER novelty at the heart of the Yes series is the notion that the politicians don’t run the country anyway. The real captains of the ship of state are the shadowy, unelected public servants who beaver away in the bureaucracy while governments of this or that political stripe come and go.

This was more true when the first scripts were written, when Britain still had a disinterested civil service that was peopled with tenured bureaucrats, BT (Before Thatcher, whose election coincided with the broadcast of the first program). These days the Humphrey Applebys are more likely to be as temporary as the party they serve. But there are always lower level, but influential, public servants keeping a conservative hand on the reins of power. Think Godwin Grech. So the clever cabinet minister keeps on side with them all because there is nothing as destructive in government as a disgruntled, leaking public servant or, as we know, one still secretly serving the previous government.

If you think the creators of Yes Minister were stretching things back in the early 1980s, consider a conversation between John Langmore, later to be the federal member for Fraser, and the Rt Hon Paul Keating, who had become treasurer in 1983. As Mr Langmore told me, “I was working as Keating’s economic adviser during the election campaign (1983) and after we won took part in the discussions on the day after the election with John Stone, the secretary of the Treasury, and in the discussion with Prime Minister Hawke that afternoon and the following day about what the incoming government should do about the exchange rate. We did not accept the Treasury advice about the devaluation by the way; they advised five per cent, the Reserve Bank ten per cent and we all agreed on ten.

“Having been his economic adviser I had hoped to become his chief of staff but he said to me about three days after the election that ‘I learnt when I was a minister in the last weeks of the Whitlam government that the way you survive in these jobs is to do what your department tells you to do and that is what I am going to do now. I know that you would like to be my chief of staff but the Treasury don’t want you and so they are going to nominate one of their own. The intellectual strength is over there (pointing to the Treasury building) and there is no way that you can match them. You can stay on as my economic adviser if you like.’ So that is what happened. (The point was not, of course, that a staff person could replace a whole department, but that a chief of staff could offer a somewhat different perspective to the department which could have enriched the discussion about priorities, policies and decisions.) I resigned after three months or so because Paul was doing exactly what the Treasury told him to do and giving me relatively little chance to take part in the discussions. He went on doing so for three or more years.”

That is how a political party with a long engagement with Keynesian economics came to enthusiastically embrace the new dogma of neo-liberal economic rationalism.

Should we be angry, rather than amused? As a satirical attack on the institution of politics the Yes programs are more savage than we would expect or tolerate on any other institution. We would not be so sanguine about a similar cynical demolition of the clergy in which they are portrayed, without exception, as hypocritical child molesters. Both the clergy and the devout would, quite rightly, object. We wouldn’t be happy with a swingeing attack on the teaching profession or even the medical profession. We may secretly fear that doctors are pompous, greedy and vain, not so far removed from their witch counterparts in usefulness, but we all think that our own doctor is the exception. We may mistrust police, but we wouldn’t be relaxed about a sitcom based on the proposition that they are all, without exception, violent and corrupt; it wouldn’t have the recognisable connection with reality that is the basis of all good satire. But Jay and Lynn don’t concede exceptions and we are happy enough with the result. (Although one former MHR does report a doctor effect – his own constituents wrote him kind letters, treating him as the exception to the rule.)

The writers emphasise the universality of their stereotype by making Jim Hacker an MP without any identifiable party. Their initial research was talking to insiders in the governments of Wilson, Heath and Callaghan, but just as the first episode was ready to air Mrs Thatcher moved into Number 10. This meant that care had to be taken to avoid any personal pronoun attached to Jim’s PM. And to de-party him completely he turns up in the first episode, for the reading of the poll results in his constituency, sporting a white rosette on his lapel rather than the socialist red or the Tory blue.

I asked Humphrey if I too would end up as a moral vacuum. His reply surprised me. “I hope so,” he told me. “If you work hard enough.”

– The Rt Hon James Hacker

THE POLITICIAN sans ideology is familiar to us in all liberal democracies. As Gore Vidal more or less says: We live in one party states. The governing party is the Capitalist party. It has two branches – Democrat/Republican, Labour/Tory, Labor/Liberal etc. Or as Marx put it, the modern state is merely “a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.” If you suspect he is overstating the case then try to spot the difference between Thatcher and Blair or Howard and Rudd.

An American sociologist once explained to me his compatriots’ attitude to politics in this way. We venerate the office, he said, while frequently being disappointed with the incumbent. Americans are often disappointed, but they travel in hope that one day an Abe Lincoln, whose personal integrity will match the majesty of the office, will reappear. It probably won’t happen, so the cynic may, indeed, be the realist.

But veneration of the office does not inhibit mockery of the incumbent. That’s My Bush, the sitcom in which Timothy Bottoms brilliantly portrayed an idiot George W., flashed briefly across our screens in 2001 and was sadly brought to an end by the events of September 11 in that year. Americans do satire and irony just as well as the British, it’s just that we don’t get to see it on commercial TV.

Perhaps we should just enjoy Yes Minister and Yes, Prime Minister and not over-analyse the program and its effects. The Netherlands, Canada, Turkey, Sweden, Portugal and India all made their own versions of the programs. In Holland Sir Humphrey was played by a woman and Bernard by a Moroccan called Mahommed. It would seem that the phenomenon of the despised politician and public servant is universal, although it would be interesting to know what subtle variations occur from culture to culture.

For ourselves, we can observe that there are not too many countries in the world in which politicians would permit the state broadcasting service to mock them mercilessly. For that small boon, much thanks.

Jim Hacker: “We’ve got to give him something. I promised.”

Sir Humphrey: “Well, what’s he interested in? Does he watch television?”

Jim Hacker: “He hasn’t even got a set.”

Sir Humphrey: “Fine. Make him a governor of the BBC.”

Now that is really biting the hand that feeds you. •

Postscript: The recent film, In the Loop, a bitter take on contemporary Whitehall, brings the inside story up to date. Writer/director Armando Iannucci has been inspired by the diaries of the egregious Alastair Campbell, Tony Blair’s director of communications. In The Blair Years Campbell represents himself as the true governor of Britain while Blair dithered around in Number 10. His avatar in the film is Malcolm Tucker, communications chief in the office of minister for international development, Simon Foster. Tucker is loud, arrogant, foul-mouthed and vulgar and regards himself as superior to the pathetic elected MP for whom he is supposed to be working, exactly as Campbell cheerfully describes himself in his self-serving diaries.

When Campbell was asked what he thought of the Tucker character (he didn’t dispute that it was supposed to represent him) he said: “I was too bored to be offended.”

Forget Sir Humphrey, the discreet permanent secretary – the real power now is in the hands of the oafs-of-spin who mediate the MPs to the media. It is they who determine what MPs will say and when and to whom they will say it. Sir Humphrey seems a harmless impediment to democractic government by comparison.

Terry Lane is a Melbourne-based writer and broadcaster.

Photo: Nigel Hawthorne (as Sir Humphrey Appleby), Paul Eddington (as Jim Hacker) and Derek Fowlds (as Bernard Woolley) in Yes Minister.