Why does the Australian media publish opinion polls week-in, week-out, all year, every year, no matter how far away the next election? And why are they studied, discussed and obsessed over?

The first scientific polls appeared in the United States in the 1930s, and were brought to Australia early the following decade by Roy Morgan. They were invented to help people anticipate imminent election outcomes. Eight decades later, with so many pollsters polling so frequently, poll data has become almost an end in itself.

The sandstone Australian outfits, Morgan, Newspoll and Nielsen (which last month conducted its last survey for Fairfax), were joined a decade ago by Galaxy. More recently, Essential arrived with weekly online surveys (using random samples from pre-arranged panels), and then automated surveys from companies like ReachTEL began dotting the landscape. The last category – also known as “robopolls” – are dirt-cheap to run once the setup expenses have been covered. What they lack in response rates they make up for by carpet-bombing households.

Within the political class, Newspoll is the most watched and most influential. Published every second Tuesday in the Australian, the poll results are interpreted for readers by the paper’s political writers. It’s that interpretation – captured in headlines and opening paragraphs – that’s repeated, largely unquestioned, on ABC radio news bulletins and in other media across the country. No one holds a gun to their heads to force them to follow the Australian line, but something about the news-creation process means that they do. It’s probably just the path of least resistance.

Opinion polls tell the political class how a government or opposition is “travelling.” Particular events are interpreted through the figures, and then often reinterpreted once new polls come up with different results. Depending on what the next poll says, a political decision will be judged a stroke of genius or a dismal blunder.

To varying degrees, pollsters use their published political surveys as marketing tools. They usually earn the majority of their income from other work; delivering authoritative political news in news bulletins and on front pages around the country brings them free advertising of a very high grade. That’s why many of them discount their work for media outlets, or even conduct the polls for no fee.

And then there are the parties’ private pollsters. Their work tends to be qualitative rather than quantitative. Versions of their “findings” are doled out, from time to time, to friendly journalists. Selective at best and fictional at worst, they are released into the public domain for particular political purposes and tend to be reported faithfully. Journos need to keep the communication lines open, after all. It makes for a very fine arrangement – for one side at least.

Party pollsters are financed partly by taxpayers through public election funding. More controversially, they sometimes perform paid government work when their side is in power. These outfits – currently Crosby-Textor for the Coalition and UMR for Labor – also conduct market research for other clients. No less than the public pollsters, they use political work as marketing exercises.

The party pollsters cultivate their images as political gurus, highlighting and taking credit for the good results and airbrushing out the unfortunate ones or shifting the blame onto others (usually the party leader). The Canberra press gallery tends to comply here, too. Like any producer, it’s in political pollsters’ interests to play up the indispensability of their goods. The fourth estate plays along because poll results are embedded in the “horse race” style of analysis that makes up so much political reporting.

The routine preface to the media reporting of survey results – “If an election had been held on the weekend…” – is terribly misleading. No poll can tell us what result an election last weekend, preceded by a campaign, would have thrown up. A pollster contacts a person and asks him or her to imagine there is an election today – and how would you vote? It’s a preposterously hypothetical and artificial exercise: a silly question eliciting silly answers.

Surveys that ask people how they would vote if a particular event (such as a leadership change) occurred are particularly misleading, simply piling hypothetical onto hypothetical. Yet apparently Labor Party machinemen spruiked just such “findings” around caucus in preparation for the 2010 leadership change.

As the actual election approaches, voting intentions surveys start to become more meaningful. After the election is called the pollsters’ wording changes to “How will you vote on Saturday the...?” Suddenly the polls (and the polled) are focusing on a real event.

Pollsters take their final surveys, in the days before election day, very seriously (Newspoll, for example, gathers about double the usual sample) because these are the only testable ones. And because these surveys are done so close to polling day, they are usually close to the actual result. But this “accuracy” is touted all year round, all term round, as a reason to take all a company’s polls seriously.

Commentators claim to be able to foretell all manner of events from voting intentions, preferred prime minister and approval ratings, but they can’t really. So what we’re really left with is “research” that doesn’t tell us much that is useful, at least for its original intended purpose, but which is closely watched by the political class.

The gurus’ qualitative work is really no better, although other of their activities, such as assisting parties or governments to sell messages, can be more useful. But it’s all much more hit-and-miss than the practitioners would care to admit.

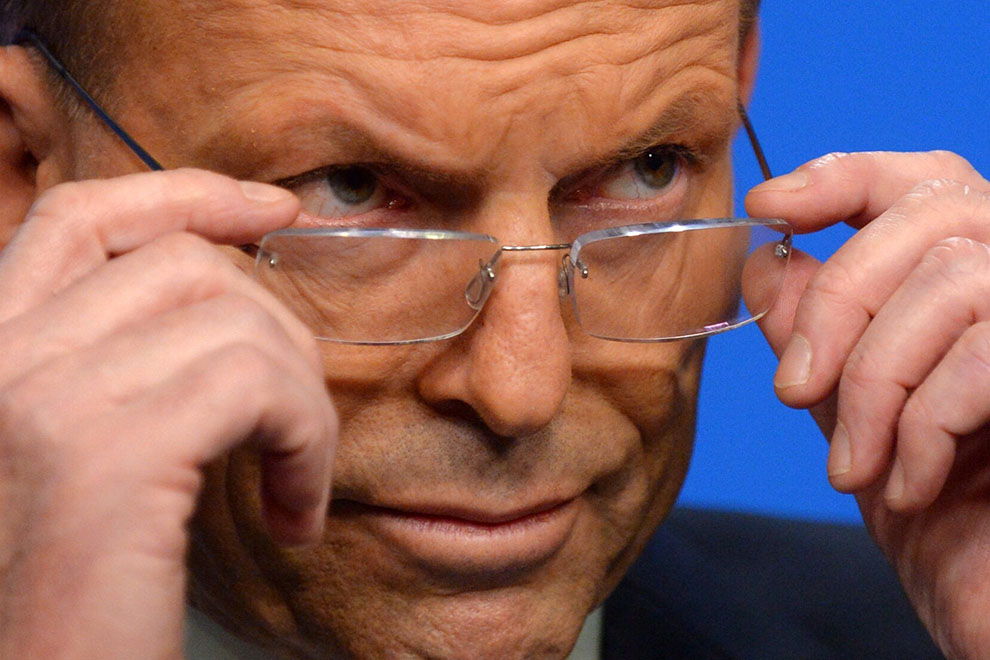

Even after an over-hyped Malaysia Airlines–induced “boost” in satisfaction ratings, the most recent Newspoll had Tony Abbott on just 36 per cent satisfaction and the government trailing in voting intentions after preferences 46 to 54. At the equivalent time in his prime ministership, Kevin Rudd enjoyed 65 per cent satisfaction and the government led 54 to 46. John Howard was on 52 per cent satisfaction and the Coalition was in front 53 to 47.

But Rudd didn’t even make it to the next election. Howard did, and scraped back, and then comfortably won two more.

The Abbott government might be performing “badly” in the opinion polls but today’s numbers mean almost nothing. At the same time they mean a lot, because political players can’t ignore the way they influence what the media sees as the “narrative.”

In the twenty-first century, political leaders seem increasingly disposable. Abbott would be aware that if the polls continue as they are, speculation will arise about his prime ministership. His actions will increasingly be interpreted through the polls. On the Labor side, new rules have provided institutional ballast to the leadership, but they can be easily reversed.

One day the forty-fourth parliament will end, and we’ll be starting a new one, most likely with a re-elected Coalition government. The mid-2014 polls will be long forgotten, and probably, with hindsight, judged laughably unreliable.

We kind of know this right now, but we can’t help ourselves. We keep reporting the polls. •