A Way Through: The Life of Rick Farley

By Nicholas Brown and Susan Boden | New South Publishing | $39.95

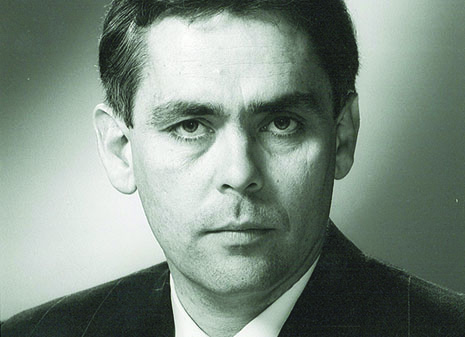

BY ANY reckoning, Rick Farley was a remarkable Australian – a peacemaker in a time of conflict, a conciliator in a time of division – but the term most used to describe him in his lifetime – enigmatic – is just as apposite six years after his death. And a thoroughly researched biography that discusses many of the key events in his life and political career merely adds to the enigma.

I was first aware of Rick Farley and his activism on behalf of the Cattlemen’s Union in the 1970s, and it was on a trip to Brisbane that a bumper sticker, providence unknown, caught my eye: “Chuck you, Farley.” It made me smile: the man was obviously treading on toes, and that became a kind of hallmark in his subsequent career: a man who never went with the flow.

Best known for his decade as head of the National Farmers’ Federation, Farley drove the peak farming body into unfamiliar territory, forging an unprecedented alliance with the Australian Conservation Foundation and its activist head, Philip Toyne, in 1989, and winning from the federal government a commitment to establish Landcare Australia. In 1993, he was at the forefront in negotiating native title legislation in the wake of the landmark 1992 Mabo decision by the High Court, which had sparked fear, consternation and uncertainty in his constituency.

His expertise and skills were in demand and his portfolio bulged with public service: chair of the NSW Resources and Conservation Assessment Council, chair of the Lake Victoria Advisory Committee, an Ambassador for Reconciliation, co-chair of the NSW State Reconciliation Committee, member of the National Native Title Tribunal, member of the executive committee of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, and a member of the Australian Landcare Council, the Australia China Council and the Commission for the Future.

Determination was a key element in Farley’s character, but the quality most often commented on was a finely honed political instinct that told him when to go hard and when to back off, who to talk to and who to avoid, and what was possible and what might hold for another day.

The question of just who Rick Farley was is a difficult one. There were many Rick Farleys, even to those who knew him well. The old 1970s hippie was still in evidence when he ran the Cattlemen’s Union out of very un-hippie Rockhampton, cutting an incongruous figure with his long hair and already passé flairs before he was quietly advised about his “attire.” He took to moleskins and R.M. Williams boots, but even then he would alternate, in his later Farmers’ Federation days, with a pinstripe suit, just as his negotiating style could switch from a bag of marijuana plopped onto a table to the production of a bottle of whisky accompanied by the ritual crushing of the bottle cap.

The other question – the why – is even more problematic. A driven man in whatever role he found himself, a plausible explanation of Farley’s restless pursuit of seemingly unattainable goals seems frustratingly beyond reach. Why did this man, whose need for middle-class creature comforts was as strong as anyone’s, push himself to spend so much time travelling to and from physically uncomfortable places and throw his considerable energies into causes on behalf of Australia most disadvantaged people, its Indigenous inhabitants? His close friend, Mick Dodson, was as puzzled as anyone, remarking when the idea of a biography was put to him after Farley’s death: “I’d like to understand why he devoted so much of his life to my people.” Farley never did explain.

An even greater challenge is in trying to locate Farley in a political frame: the ex-actor and ex-journalist who worked as a Labor staffer, ran an organisation for an industry with deep old Country Party links and another closely associated with the emerging New Right, playing a curious role in the ill-fated and ultimately destructive push by Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen to run for Canberra, and pushed an industry traditionally hostile to Indigenous causes closer to accommodation before running for political office for the centrist Australian Democrats.

The conundrum here, as the book shows, lies in how these apparently contradictory positions were somehow consistent with who and what Rick Farley was: a part of much, but belonging nowhere; a perpetual outsider who was, for a time, an influential insider; but someone whose convictions, for what they were, never wavered.

But it would be a mistake to see Farley as a dreamer or even an idealist; he was, at bottom, a hard-nosed pragmatist. Underpinning his political activism and his modus operandi was a firmly held view that the future of the Australian environment depended on a partnership and cooperation between Indigenous Australians and those settler Australians whose very livelihoods depended on conservation of the rural ecology and the Green movement.

In an Australia Day address in 2003, Farley expressed the view that his country was “a bit lost: still not managing change equitably,” and unless natural resources were used in a sustainable way, Australia was simply mining the future. Perhaps it was as close as he came to articulating a political credo when he said: “Unless the relationships between our citizens are respectful and inclusive, we are a divided and diminished society. To me, these are the defining features of Australian culture and identity.”

It was perhaps not unusual that Farley would, in what were to be his final years, find solace in a personal sense with another perpetual outsider who also made it to the inside – the NSW Labor MP, Linda Burney, child of an absent black father and a white mother.

A deeply complex man, an intensely private man who forever felt the pain and emptiness brought on by his father’s absence, there is an echo in Farley of the haunting and haunted solitude of the Australian continent, somehow always just beyond the reach of words. This biography, while not penetrating the enigma, is a fitting tribute to a great Australian whose deeds and spirit live on after him. •