Brisbane’s deputy lord mayor was at the Commonwealth Games in Christchurch in January 1974, lobbying for the Queensland capital to host the 1982 Games, when the Brisbane River broke its banks.

On the night of the opening ceremony, 24 January, Cyclone Wanda crossed the coast at Double Island Point north of Noosa. It didn’t have the devastating winds of cyclones like Ada and Althea that smashed the Whitsundays in 1970 and Townsville in 1971, and it weakened rapidly, but the monsoonal trough it forced south to Brisbane stayed there for days. Small oscillations in its movement and intensity generated many stretches of drenching rain.

Across Brisbane, 600 millimetres fell on the first three days of competition in Christchurch — twenty-four inches, or two feet, in the language of the time. This was three times the city’s average rainfall for January, its wettest month. On 28 January the trough weakened and retreated north. A drier, cooler air mass from the south finally brought some blue sky to the capital of the Sunshine State.

The river peaked in the early hours of 29 January at a height not seen since 1893. Residents woke to find about 13,000 buildings damaged. Children due back at school that morning got an extra week added to their Christmas holidays.

Across the Tasman in Christchurch, Australia had won a bag of gold medals while the river rose. Raelene Boyle retained the 100 metres sprint title she won in Edinburgh, fourteen-year-old Newcastle schoolgirl Sonya Gray won the women’s 100 metres freestyle and Mexico Olympic champion Mike Wenden the men’s. As the waters receded, Boyle and Gray added the 200 metres to their 100-metre golds and Don Wagstaff completed a double in the diving pool.

The deputy lord mayor reported Brisbane’s promotional T-shirts “were without doubt the most sought-after item at the Games.” Its souvenir match boxes and coasters “were widely distributed and caused much interest.” Sandwiched amid coverage of the floods, the full-page advertisement for Brisbane’s bid in the Christchurch’s main paper, the Press, caused “some concern,” but it was not fatal because “most people realised that occurrences such as these were not the normal thing.”

Whether or not the 1974 flood was abnormal depended on the time scale. The “River City” had not seen a flood as high in the twentieth century. During the nineteenth century it had seen four as high, including three much higher, and a total of eight floods classed as “major” according to the Bureau of Meteorology’s current classification system (3.5 metres at the City Gauge). Only two other “major” floods occurred in the twentieth century, the last in February 1931. This century is different again. The February 2022 flood was Brisbane’s second major flood after the even higher one in January 2011, and a further “minor” one occurred in January 2013.

The inaugural meeting of Brisbane’s Commonwealth Games Committee was held two months before the Christchurch Games. Chaired by lord mayor and sports fan Clem Jones, the meeting was told an application had already been lodged for Brisbane to host the 1982 Games. Business representatives thought the city council’s report on possible venues was technically excellent but lacked ambition. By 1982, they thought, the city “would deserve a sporting complex of world-wide standard.”

Council representatives baulked at the zeal. They “could not commit the City to structures which could become ‘white elephants,’ or to a financial burden which it might be virtually impossible to meet.” After the floods, the committee’s next meeting was deferred, but not for long. Lord Mayor Jones and his deputy flew over the city in the 4KQ helicopter and were “amazed at the number of places which could be regarded as possible sites for the Games.” A sites sub-committee was whisked around nine possible venues in a council bus just three months after the flood’s peak.

The choice narrowed to the Northside versus the Southside. Deputy Mayor Walsh, representing the Chermside ward on the Northside, wanted Marchant Park redeveloped. Mayor Jones, representing the Southside’s Camp Hill ward, liked a site in the new suburb of Nathan, adjacent to the Mt Gravatt Cemetery and Griffith University, which would accept its first students the following year.

In late July, six months after the flood, a decision was reached: the Southside. It would be closer for visitors staying at the Gold Coast and more convenient for residents of the rapidly expanding southern suburbs.

The campaign for Brisbane to host the 1982 Games succeeded, although the likely “phenomenal” cost was much criticised. At the Montreal Olympics in 1976, where the Commonwealth Games Federation met to decide the venue for the ’82 Games, Brisbane found itself the only bidder. Montreal’s diabolical financial outcome scared others away.

New lord mayor Frank Sleeman assured Brisbane ratepayers they would pay only for the “bare essentials.” A new stadium would be built in the new suburb, but it would have a permanent grandstand seating just 10,000. “Temporary” seating would accommodate another 48,000. Work began immediately and the venue was first used in late 1975. Two years later, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, it was named the “Queen Elizabeth II Jubilee Sports Centre,” or “QEII.”

There was one big problem with siting the main stadium on the top of a hill. One of the signature events at major games, the marathon, traditionally starts and finishes in the stadium. After the local distance-running community rejected a plan for the runners to complete three laps along the nearby South East Freeway, ending with a sharp climb back up to the stadium, organisers agreed to start and finish the race away from the stadium. (It was men’s only; the first women’s marathon was run at the 1986 Games in Edinburgh.)

A flatter, “city” course was mapped, like those becoming popular in places like New York, Chicago and London. For Brisbane, this meant using the river. The new route started and finished on the south bank, opposite the CBD. It headed out through the city and “The Valley,” across Breakfast Creek to the river at Kingsford Smith Drive, then doubled back to the river bank around the University of Queensland. TV cameras would capture the city at its most picturesque, spectators would get accessible viewing spots, runners would appreciate the cool breeze and flat ground in a city that doesn’t have much of it.

Held the day before the closing ceremony, the marathon did not disappoint. Big crowds lined the route. Australian favourite Robert De Castella found himself well behind two Tanzanians who were close to world record pace at the halfway mark. He set off to chase alone, catching Gidamis Shahanga just before they passed a heaving Regatta Hotel, then ran side-by-side with Juma Ikaanga for a kilometre along Coronation Drive (named in 1937 when George VI was crowned). Morning peak hour traffic on the Sydney Harbour Bridge slowed as commuters tuned car radios to the struggle. Finally, “Deek” made a decisive break and won by twelve seconds.

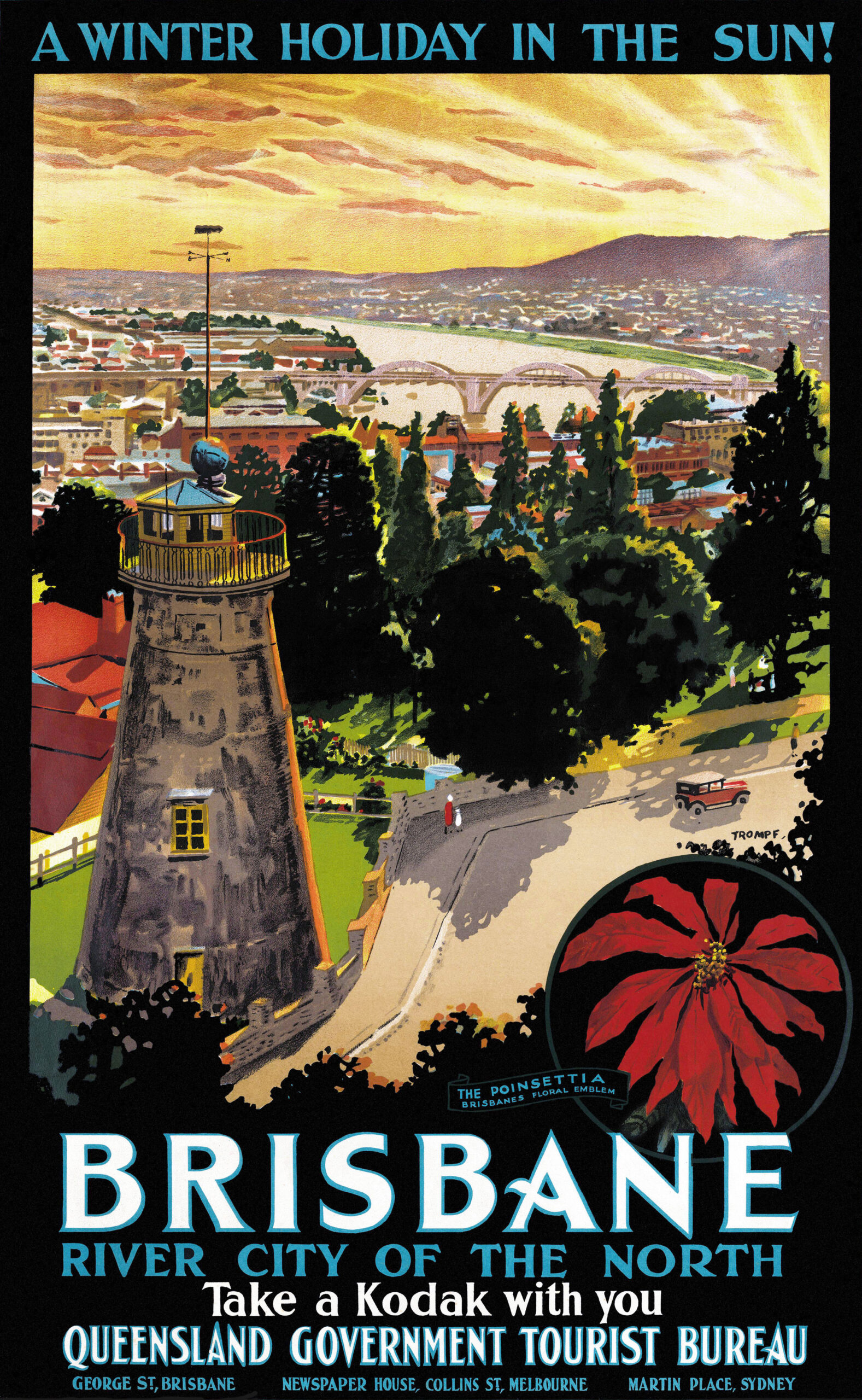

Building the main stadium for the Commonwealth Games on a hill in the southern suburbs had helped, paradoxically, and indirectly, to re-energise an old conceit. Decades earlier, tourism promotions dubbed Brisbane the “River City.” Soon, the first of several major arts and cultural organisations began setting up on the South Bank. Expo 88 would draw millions of people from the suburbs, the state, the nation and the world to the banks of the big river.

Despite the best intentions, QEII struggled to avoid the fate those Brisbane City Councillors feared: becoming a white elephant. Track and field events take centre stage in Olympic and Commonwealth Games but local athletics events, even the biggest interschool carnivals, attract much smaller crowds at other times.

For a while, in the 1990s and early 2000s, QEII was back in business. On joining the national rugby league competition in the late 1980s, the Brisbane Broncos played at the sport’s traditional home in the city, Lang Park. A few years later, after the temporary seating at QEII was made a little more permanent, they moved there and started drawing Commonwealth Games–like crowds to the renamed “ANZ Stadium.”

Annual State of Origin matches against New South Wales, though, stayed at Lang Park. The regular monster crowds at ANZ declined. Eventually the state government and others decided to revive the old cauldron. The two “Origin” matches played at ANZ in 2001 and 2002 while Lang Park was rebuilt were the last.

In 2003, the Maroons and Broncos returned to the new “Suncorp Stadium.” They have been there ever since, sharing the venue with the Queensland Reds (rugby union) and Brisbane Roar (soccer). Last year, it was at Suncorp that the Matildas played their World Cup quarter-final against France, which ended in that epic, victorious penalty shoot-out.

QEII went back to being a track and field venue, the Queensland Sports and Athletics Centre, “QSAC.” It was used as an evacuation centre during the 2011 floods. After Brisbane won the right to hold the 2032 Olympics, there was a chance it might be revived again as a temporary venue for cricket and AFL while the traditional home of those sports in Queensland, the Gabba, was being remade as the main Olympic stadium at a cost of $2.7 billion.

That was until Monday, when QSAC got an even bigger future. Queensland’s government considered the recommendations of a committee set up to propose further options after the earlier rejection of the Gabba rebuild. The committee recommended that a wholly new stadium be built at Victoria Park, at a cost of over $3 billion, and eventually replace the Gabba as the home of cricket and AFL in Brisbane. Both recommendations were rejected. (Victoria Park was one of the sites rejected by Clem Jones’s 1974 committee.)

The Gabba is going to stay the Gabba, with a modest upgrade. Victoria Park is going to stay Victoria Park.

The winner is… QSAC! The stadium on the hill will rise again to host the track and field events at an Olympic Games fifty years after it staged them for the Commonwealth Games. At a cost of $1.6 billion, permanent seating will be increased to 14,000, and total capacity will touch 40,000 for the period of the Olympics, some way below the 1982 full houses.

The other winner is Suncorp Stadium, with its larger capacity of more than 50,000, which will get the opening and closing ceremonies.

The marathoners? They will surely follow the river again, winding out, back, out and back, sticking to the old, deceptively gentle watercourse that has always drawn people to this place. •

Information about Commonwealth Games planning is taken from Brisbane City Council committee minutes and files, and about the 1974 floods from the Department of Science/Bureau of Meteorology’s “Brisbane Floods January 1974” (AGPS, 1974). Other information drawn from Melissa Lucashenko’s Edenglassie (2023), Margaret Cook’s A River with a City Problem (2019) and Jackie Ryan’s We’ll Show the World: Expo 88 (2018), all published by UQP.