The dogs are barking. Ominously.

Politics generates jokes. It is one milieu in which sardonic observations, gratuitous character readings and the occasional illuminating witticism proliferate.

But it is always instructive to look at who is making jokes about whom. If a government is on top of its game, the best an opposition can do is make some fun among themselves (and anyone else who will listen). Occasionally funny, but mostly not, it is, as a rule, the desperate bleat of the impotent.

When a government has an opposition on the run or running in circles (or even contemplating a leadership change), government members are prone to tell either superman-type jokes about their own invincible leader or make pathetic weakling jokes about their opponents. You can lose an election, take a beating in the polls, get pulverised in parliament – but the jokes can be the cruellest barbs of all. And that is what hurts most in politics: not being taken seriously.

Much of the joking in politics, it seems, is on the government side. Opposition is very much like the line from the Monty Python sketch about the Nazi leadership hiding out in the English countryside and plotting a comeback: there’s not much fun in Stalingrad. But when they make jokes about their own on either side of politics, it is worth a listen as it can be very revealing about the mood of the party.

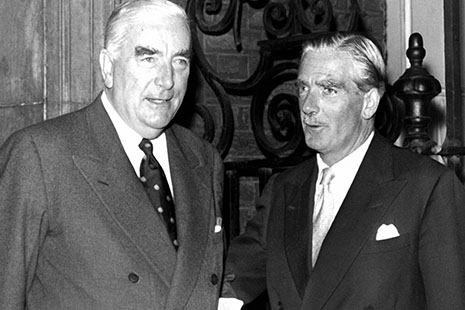

The nearest I have ever come to finding a Liberal joke about the venerable Bob Menzies was a polite schoolboy snigger expressed by the anointed one, Harold Holt, shortly before he assumed Ming’s mantle in 1965. It was not a comment expressed over a drink among colleagues, but rather was in a letter to an old friend and referred wryly to how Menzies showed off the archaic accoutrements – funny hat and all – of his sinecure as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, to which the Queen appointed him as successor to Sir Winston Churchill.

Very few, if any, Labor people mocked Gough Whitlam. Stories abounded, to be sure, about his superiority complex, but these were always told with a sort of awe; they acknowledged Whitlam’s stature rather then demeaning it.

On the other hand, during the troubled reign of Billy McMahon, prime minister 1971–72, the best McMahon jokes came from the Liberals. After the Liberals lost office in 1972 and Bill Snedden became leader of a deeply divided and restless party, the Liberal jokes about him had a nasty edge: McMahon, in Liberal humour, was merely bumbling and incompetent whereas the jokes about Snedden suggested a fool out of his depth and made fun of his humble origins and his early career as a newsboy. (That his own side failed to take him seriously must surely have emboldened the cartoonist Larry Pickering to depict him as Mediocre Man.)

When Snedden was succeeded by Malcolm Fraser in 1975 the jokes stopped. What internal jokes did emerge about Fraser – and there were few – were a bit like those about Whitlam: he’s a big bastard, but at least he’s one of us.

Throughout the troubled 1980s, as Andrew Peacock and John Howard chased each other through the revolving door of the Liberal Party leadership, you did not have to be too far away from the party room to hear decidedly unflattering stories about Howard’s plodding earnestness and Peacock’s stratospheric vanity. At least it indicated the allegiance, at that particular moment, of the teller.

In more recent times, as Howard consolidated his ascendancy, Liberal jokes dried up and the humour shifted to Labor: Kim Beazley’s size and verbosity; Simon Crean’s unpopularity with almost everyone; Mark Latham’s unique Lathamness. Kevin Rudd jokes, sadly, have been few and far between.

Which brings us, almost, to the present. Brendan Nelson had not been in office two weeks before I heard a Liberal MP – and one who admitted having voted for him – telling a joke about Parliament House staff advising Nelson not to unpack his things just yet as office moves were becoming very costly. Another prominent Liberal (who voted against Nelson) borrowed an old American joke that harked back to the hapless Spiro Agnew: Mickey Mouse had taken to wearing a Brendan Nelson watch.

And now to Malcolm Turnbull – about whom, I have to say, little new has been joked in decades. The same stories that went around the legal fraternity in the 1980s, the business world in the 1990s and later the monarchy-versus-republic stoush – recycled faithfully every time - have now been resurrected by his own Liberals. One Liberal MP was loudly proclaiming in a Canberra restaurant that Malcolm Turnbull’s ego had not only its own postcode but also its own electoral enrolment. (What is most damning here, and quite unforgivable, is that the MP was relating this as though it were new. Does the Liberal Party have no corporate memory?)

Turnbull, still languishing in the Rudd-coloured polls, is far more vulnerable than generally realised. It always needs to be remembered that the Liberal Party has a decidedly instrumental view of leadership, quite uncoloured by sentiment or loyalty: it is about who can, in the short term, deliver government. Nelson was making no impact on the polls; Turnbull is similarly floundering. Labor (and Rudd’s popularity) is undiminished in the latest Newspoll and Turnbull’s own satisfaction ranking as the alternative prime minister has dipped from a brief high of 53 per cent in early November to a new low of 44. (Rudd’s satisfaction in the same periods was 65 and 53).

That Turnbull has failed to inspire his own troops with the mixture of fear and awe that Menzies and Fraser managed (and even Howard as he got into prime ministerial stride) is a real danger sign, and there is no guarantee that he will lead the Liberals into the next election. His populist bent and predilection for chest thumping are increasingly being seen as bluster – by the public, and most importantly, by his own party.

Not only has he failed to cut it with the public, he is facing mounting resistance in his own ranks as much for what he does as how he does it. A self-made person (as Turnbull is) is the Liberal ideal, but the qualities that self-make a man or woman are not the qualities that endear that man or woman to colleagues who believe in being consulted.

But it is not only Turnbull’s personal qualities that are failing him, it is his lack of understanding of politics and the modicum of strategic thinking that is required to gain traction in that fierce arena. He shut the door in the government’s face over support for the fiscal stimulus package in the face of opposition from his own ranks, and then criticised the government for failing to talk to him. Hello? It might have been a macho act for the benefit of his uneasy supporters, but he has painted himself into a corner and might just have made the Liberal Party irrelevant in the current crisis. And is Peter Costello smirking or not? If he is, why? More importantly, why is he still there?

It is really a topsy turvy world when a Labor prime minister moves to save capitalism and a Liberal opposition leader says no (presumably on the ground that such a rescue would violate the principles of a free market). Leaving aside the argument about whether you should give more food to an obese man suddenly deprived of excessive food – and this is surely the right analogy for publicly funded bailouts of a system that has manifestly failed – what we have here is certainly the very essence of farce: the juxtaposition of the incongruous.

That surely is a starting script for a whole raft of jokes – but the only ones we are hearing in Canberra are at Malcolm Turnbull’s expense. He wears his crown most uneasily. •