Wolfgang Sievers

By Helen Ennis | National Library of Australia | $49.95

Beyond Reasonable Drought

By the MAP Group | Five Mile Press | $39.95

IN THE early sixties I had a professional photographer friend, whose work I admired, who insisted that I look at the photos of Wolfgang Sievers if I wanted to see something truly special. And I did and it was.

Sievers’s monumental images, created for a range of industrial and architectural clients, are technically breathtaking. The wide tonal range, the almost inconceivable depth of field, the fineness of the grain, the control of perspective and the dramatic compositions were all marks of a craftsman who knew and had mastered the physics and chemistry of photography.

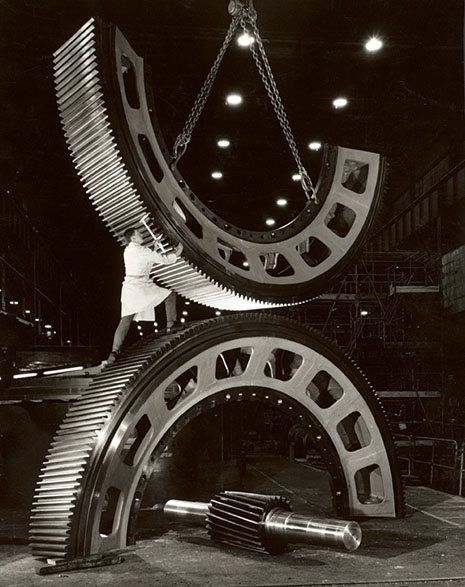

A Sievers photograph was the very antithesis of Henri Cartier Bresson’s “decisive moment” – the ephemeral image caught in a fraction of a second and forever preserved. Sievers’s photos are constructed. They are static tableaux, first imagined and then planned and arranged, dramatically lit and executed. His famous photos taken in the Vickers Ruwolt plant at Richmond, in Melbourne, were staged at night when the workers had gone home and the huge gears could be hauled into positions that were totally inappropriate from an engineering point of view but pictorially magnificent.

He cleaned up the machinery, the product and the solitary worker or engineer. He carried a razor to give them a quick shave and occasionally swapped his clean shirt for their dirty one. He was creating images of industry and worker uncannily like those coming from Stalin’s Soviet Union, except in his case they celebrated the brutal hubris of capitalism at its most optimistic and triumphant rather than the glories of the Soviet Socialist Republic.

Sievers was a product of the New Photography school, which had its origins in Russia and Germany before 1939. Until 1938 he studied at the Contempora School of Applied Arts in Berlin, where the guiding principle was the concept of art united with industry in the service of society. There was no place for the wispy romanticism of Pictorialism in this school; here everything was sharply in focus, meticulously composed and tonally (monochromatically) perfect.

Blown to Australia by the ill wind of Nazism, Sievers had no trouble finding commissions in his new country. His work was admired and his services were sought by confident postwar industries. These days his photographs are like a splendid memorial to industrial glories past. We no longer make gears (the Vickers Ruwolt site has long since been built over with flats) or matches or Kiwi boot polish.

The National Library of Australia, which holds the Sievers’ collection, has published this monograph by photographic historian Helen Ennis. It is a fitting tribute to an important artist. The works reproduced are a cross-section of his output, showing his strengths and weaknesses.

His weaknesses are on display in the portraits and informal shots – he was more in sympathy with machines and buildings than with people, and more at ease with the static than the mobile. His best works have no humans in them at all. They are cold, hard and brutal. Those that do show people, such as his colour photos for hotels in Melbourne and Queensland, are amusingly dated and quaint.

Sievers’s politics were left-leaning – he alienated some clients when he opposed the Vietnam adventure in the sixties – and towards the end of his life he came to reflect on the contradiction between the work of which he was most proud and the ethics of his corporate clients. He worked for some of the biggest mining companies, and he was not unaware of the issues involved.

“I am quite aware of the moral problems confronting a responsible photographer in industry,” he wrote. “Should he be working for multinational companies at all if he believes – as I do – that Australia should have retained 51 per cent ownership of its resources? Should he use his skills to hide the terrible pollution and despoliation of our country – as I have? In creating beautiful images I have glamorised industries which have often been heedless of their sacred trust to use resources wisely and take care in the interest of future generations. In my defence, so far, I have found no valid answer to these problems.”

In his defence we must say – looking at his majestic photo Gears for the Mining Industry: Vickers Ruwolt, Burnley, Victoria 1967, for example – who would have predicted where it would all end up? We were all optimists in 1967. Green was just a colour.

Today, Wolfgang Sievers’ photographs seem old fashioned. His plate camera was large and heavy and mounted on a tripod. There was not much scope for taking the spontaneous, lively picture. Where he was constrained by the cameras and chemistry of his time, the contemporary photographer can work with a digital camera, or at least a 35mm film camera, that functions like an extension of the eye. The digital single lens reflex with its lightning fast auto focus and metering is so responsive that in the moment an event is seen and registered in the brain the photograph is already taken – even, given the speed of the burst mode, taken several times. We expect to see life and movement. And, most characteristic of modern documentary photography, emotion.

THE DOMINANT emotion seen in and evoked by the photographs in Beyond Reasonable Drought is fear. This book is the work of thirty-eight photographers collaborating under the group name MAP – Many Australian Photographers. They set out to document the drought that had the country in its grip in the first decade of this century. As Andrew Chapman, the president of MAP, writes: “Dryness now inhabits our national psyche, and there is a fear that things may worsen…”

There is no doubt that misery makes great art. Hordes of kangaroos bounding through the dust; dead sheep, killed by heat and hunger; farmers walking across the dry river and lake beds – there is a heart-breaking beauty to the fear that this might not be just a climatic blip, but rather a permanent state of affairs.

Ponch Hawkes contributes a series of photographs of subjects contemplating “the one thing that they would save” when water becomes so scarce that horticultural triage is an imperative. Ian Kenins contributes a moving picture of Doreen Oliver, who makes oilskin coats in Geelong for farmers who no longer need them. Julie Milowick photographed a woman at Fryerstown in Victoria who saves water by bathing in a plastic tub and doing the laundry with her feet at the same time. It hasn’t been all gloom: water tank makers and installers are thriving, and they also get their pictures in the book.

Beyond Reasonable Drought was published in 2009 when we feared that it might never rain again. There are dramatic photos of the Black Saturday fires and the aftermath. There is despair in the faces of farmers who can neither sow nor reap.

Well, it did rain. Too much! When I first saw this book we were still looking for a promising cloud and fearing that Al Gore might be right, that this was not cyclic drought but permanent climate change. Now, revisiting the photographs, they read as a vivid, superbly captured historic document, a bit like the famous American Farm Security Administration photographs of the 1930s.

Beyond Reasonable Drought is also a showcase for the new photographic technology. Not all the photos were taken with digital SLR cameras, but many were and it shows. The pictures have spontaneity and movement. These cameras, as quick as an eye, catch the fleeting expression or the momentary event. Colour, once so difficult and expensive to use, process and reproduce, is now easy and cheap.

Every photo in Beyond Reasonable Drought is a story to be “read” – quite different from the work of Wolfgang Sievers, who has done all the reading for us. And if we presume to read Sievers’s pictures we are likely to be deceived because they are artful arrangements intended to astonish, rather than reveal the truth. Marshall McLuhan characterised the photograph as “the brothel without walls” – a frozen moment of voyeurism. That’s true of the MAP photos but not of Sievers’s compositions. But you wouldn’t want to miss either. •