Michael Gordon writes:

In 2005, after three years of trying, I was granted permission to visit the Nauru detention facility to report firsthand on the conditions for the Age and the Sydney Morning Herald. Fifty-four asylum seekers were still living there, including two families with children. Half were granted refugee or humanitarian visas in the weeks after my visit. All but two of those who remained were offered asylum in Australia late that year, but only after a team of mental health experts was sent to the island. The experts reported that a number of the asylum seekers had “a history of suicide attempts and incidents of self-harm,” and warned that the facility’s psychiatrist was finding it difficult to manage “psychotic features and suicidal thoughts.” I described my visit to Nauru in Freeing Ali: The Human Face of the Pacific Solution, published in 2005; this is an edited extract…

The camp sat behind a high wire fence, with a boom gate and sentry box at the entrance. There was no razor wire. On one side was a line of buildings, including a modest library and a computer room; on the other side was the accommodation. In between was an open area where a volleyball court could be set up. No one was in sight; the asylum seekers were either in their rooms or away from the complex (recently the detainees had been given permission to leave the camp unaccompanied). Shamel Mahmoodi, who ran the facility on behalf of the International Organization for Migration, made it plain that he was happy for me to return and interview those who wanted to speak to me, but I should confine my visit to one day. With my return flight on Tuesday and the camp closed for the weekend, Monday would be the day.

At the Chinese shopping precinct near Nauru College I ran into one of the detainees, Ali Mullaie. He had seen me arrive the day before and suspected I might be the journalist who had sent him an email foreshadowing a visit. He was wearing a white tee-shirt and his left arm was in plaster, the result of a bicycle accident. He was warm and friendly, and explained that he was hoping the principal of the college would drop by so that he could make sure the computers were ready for when school resumed. Voluntarily, Mullaie had been looking after the school’s computers and teaching students remedial reading and desktop publishing for some time.

We walked to the school and, as we waited, he told me the main threads of his story. He described how he had been forced to flee his home in the district of Jaghoori in Afghanistan in 2001, leaving behind his parents and six younger siblings. After his father was arrested twice by the Taliban, the family’s home had been searched for weapons and his life had been threatened because he was an “infidel.” It was then that his family decided he should flee. “They just wanted to get me out of there,” he said. The arrangements with a people smuggler were made by his sister’s husband and he had no idea that his intended destination was Australia until he reached Indonesia. There was no time to take family pictures or for proper goodbyes. Mullaie told me that he now struggled to visualise his younger siblings.

In November 2001 the old Indonesia coastal trader on which he was travelling from Indonesia to Australia was intercepted by the Australian Customs vessel Arnhem Bay as it made its way toward Ashmore Reef. Mullaie was at the front of the crowded vessel when a party from a second Navy vessel climbed on board. It was then that black smoke began billowing out from the front of the boat, triggering a panic on the deck. Next came an explosion and the instruction from the Navy sailors for all passengers to jump into the sea. As one of the asylum seekers who were initially refused passage, Mullaie had not been given a life jacket, so he spent almost two hours clinging to a plank in the water.

Mullaie also spoke of the pain of having his application for refugee status repeatedly rejected, and of bidding farewell to friends whose applications had been accepted. “For twenty-four hours, or two days, or three days [after the others left], my heart has been burning, feeling it’s the end of my life,” he said. “But unfortunately, it is not one time, two times, three times. Many times it has happened, especially the last time.”

The last time was the hardest because Mullaie was absolutely convinced he would be accepted. So, too, it seemed, was just about everybody else inside the camp. It was 15 May 2004 when forty-four Afghans received their decisions. Forty were accepted and Mullaie was one of four rejected. “I really could feel like all my body been numb,” he recalled. One of the IOM staff sensed his distress and offered to help him leave the area. “I said, ‘No, I can walk.’ But I tried to walk and it was very hard.”

Shamel Mahmoodi, himself an Afghan refugee, later recalled how he was told of the decision by radio and came immediately to offer support. “It’s not the end of the world,” he told Mullaie. “You’re still young, with your whole future ahead of you. Maybe this is God’s will.” Mullaie asked to be taken to the internet cafe and conveyed the news to the Australian migration agent Marion Le, who had visited the camp weeks earlier to help asylum seekers prepare their applications. “You may recognise me,” his email began. “I told you my story why I am not being able to return back to my country. You hugged me and cried with me when you heard my story. It is with regret to inform you that today… I received a negative decision.”

We talked for perhaps an hour at Nauru College. When it became clear that the principal would not be coming, we decided to walk back towards the camp. A bus made the thirty-kilometre trip around the island at regular intervals, picking up those at the shops, the internet cafe and the harbour, and Mullaie was confident that I, too, could get a lift. As we walked, children would call out to Mullaie from nearby houses. Some came up to say hello. One was named Dunstall, after the great Hawthorn full forward, reflecting Nauru’s strong attachment to Australian Rules football. Mullaie pointed out the landmarks, including the modest house where Nauru’s president, Ludwig Scotty, lived with his large extended family. Eventually, the bus came and the driver was happy enough to give me a ride.

It was almost seven o’clock when we arrived at the camp and many of those who were not on the bus were walking up the hill to meet the daily deadline for their return to camp. We agreed to see each other again on the Monday, when I would spend the day at the camp.

Over the weekend I managed to hire a car from one of the staff at the hotel and explore much of the island, including the rusting cantilever that was once used to load the phosphate onto Nauru-flagged ships. A sign conveyed a warning that was just as apt for the Nauruan economy, and maybe the country too: “Danger. This structure will fall down any time.” I ate alone in the dining room of the Oden Aiwo, where the menu seemed to become more limited each night and there was only ever one other guest.

One morning at one of the shops I came across one of Nauru’s parliamentarians buying soft-serve ice creams for himself, his wife and their two children. It was the only luxury they could afford, he said. I also interviewed Baron Waqa, the education minister, who had one daughter working in the camp and another being taught by Ali Mullaie at Nauru College. It would hurt Nauru’s economy if the camp shut down, he said, but he was sure they could manage. “We’d really like to see those people handled well and processed quickly. Some of those people have been here more than three years,” he said. “It would be good to see that they get something in the end, maybe not Australia, probably another country or something. I just hope that somebody can come to their rescue. Some people up there are really suffering.”

The next day would be the most important of the trip, and one of the more significant in more than three years of writing about the Pacific Solution for the Age. I would be the first media person given unfettered access to the camp and its population of asylum seekers. The most difficult moments would come when young men would tell me their stories of unmitigated sadness and even horror and ask what I thought. All I could offer was empathy and a link to a wider audience. One of the more awkward moments came when Mohammed Zahir Dulat Shahi asked, ever so politely: “Mr Michael, I am wondering why you come now?” It was hard to explain how, for almost the entire time he had been endeavouring to leave Nauru, I had been seeking permission to visit.

SHAMEL MAHMOODI had arranged for a room to be set aside for me to interview residents at the camp, but initially I chose to meet them in their rooms. Ali Mullaie assigned himself the task of making my job as easy as possible. He introduced me to those I had not met, interpreted some of the interviews and made me cups of tea.

Our first stop was the Hussaini family, one of two families who had been rejected twelve months earlier when twenty families were accepted. Ali Hussaini is a big man with a generous smile. He and his wife, Batool, had kept themselves busy with embroidery during their time on the island, but he was desperately worried about how his two small children, Zahra and Saqlain, were coping with conditions there. In his first interview, the case officer accepted that the family were citizens of Afghanistan and that Hussaini’s fear of the Taliban was consistent and plausible. But given that the Taliban had fallen, the claim for refugee status was rejected. The official maintained that, while it was true that many parts of Afghanistan were insecure, the lawlessness applied generally rather than against any ethnic minority, such as the Hazaras.

When the Afghan caseload was reviewed in mid 2004 in the light of new information on the level of danger, the Hussaini family was rejected again, but this time on the basis that the case officer was not satisfied they were from Afghanistan. “I give my interview in English,” Ali Hussaini explained to me. “I’m talking and he [the case officer] says I am from Pakistan because I am talking like an Australian. If I am Pakistani, you are a Pakistani.”

The explanation for his accent was simple. “I learned English here,” he said. “I worked in kitchen near about two years and they give me certificate. I always asked from the cooks, what you call this? I also learned from Zakir Hussain Jaffari. He already gone to New Zealand. He always told me: you should try to talk like Australians. Now my daughter also talk like you. When we came here she was three-and-a-half years. Now she is [seven and] talking like you. She is also Pakistani? I give my interview in English and I hope my DIMIA officer who is taking interview is very pleased about me that he is learning here, that he isn’t wasting his time. I think he is very pleased for me, but look. I am rejected.”

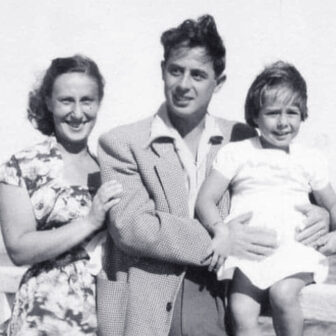

Above: The Rehmati family.

Photo: Michael Gordon

Next, I visited the extended Rehmati family, which included four children. Hussan Ali, a nephew, served as interpreter and spokesman for the group. “We heard that there is this one country, Australia,” he began, “who is accepting people who are refugees and they give shelter to them, so we decided to go Australia and after very dangerous and very difficult and long journey we reached Australia and now we trapped in Nauru, so we just request to help us and take us out from here and give us shelter in your country that we can live a peaceful life, because it is very hard for us and we cannot go back to Afghanistan. We accept that we came here illegal way, but request to John Howard government… please accept us and give us shelter. It was not our fault that we came here illegal way.”

He explained how one of the children, nine-year-old Abbas Ali, was ill for ten days after their last rejection. “When his father took him to the doctor, he said, ‘Your son is very lonely. There is no treatment.’” The older daughter, Ilham, aged fourteen, was the only teenage girl in a camp overwhelmingly comprised of young men. She had to go everywhere with her parents and said she was very depressed and lonely. “It’s very hard for me. I cannot go outside. I cannot go to the dining room. I cannot go shopping or swimming. I [only] go with my family.”

When the interview was over, I took a picture of the family outside their room. The expressions on the faces of the children were hauntingly sad.

From the Afghan families, I went to visit some of the young Iraqi men, including two Marion Le had told me about, Abuozar al-Salem and Monawir al-Jaber. Salem exuded an inner strength but said he could not understand why he was not believed or able to stay with his brother in Australia. In stark contrast, Jaber, skinny and withdrawn, appeared to be hanging on by a thread. He was sixteen when he left Iraq and told me how he had discovered while in offshore detention that his mother had been murdered. The news was conveyed by his brother, who had been accepted as a refugee and was living in Sydney. “The detention camp is a small jail and the island is a big jail. All of the island, same jail. I want to get freedom,” he said.

While another detainee, Houda al-Massaudi, was in Melbourne with her husband for treatment, the only other Iraqi woman in the camp was Wahida al-Timimi, who was there with her husband Razak. She greeted me with an impassioned monologue. “I come in 2001. Now 2005,” she said. “I very, very tired. No can sleep, no can think, no can eat. Three years and six months in here. Why? Our suffering here is too much.” She said she spent her days in their small room and relied on sleeping tablets at night. She had been flown to Australia for one operation and said she needed another. Her husband had a blood pressure monitor and was taking several medications. Showing three packets of pills, he said: “I take this for sleeping at night. This for blood pressure. This for heart.” Recently he said he discovered his wife unconscious with her eyes open and thought she was dead. He slapped her to revive her and they spent two hours in the camp medical centre. Wahida said she was also suffering psychological problems. “Sometimes my mind doesn’t work. I cannot do anything.”

It was then that Shamel Mahmoodi, the man in charge of the camp, placed the only limitation on my visit. He said he would prefer that I worked from the area he had set aside for me and not interview the asylum seekers in their rooms. For the next few hours I sat at a desk and the interviews followed a familiar pattern. An asylum seeker would come in and introduce himself. I would listen to his story, ask questions and take his picture. Many of the stories were familiar, because many of these people had been rejected a year earlier on the basis that they were from Pakistan, not Afghanistan. They insisted they now had proof to support their original claims and hoped they would be considered. Many said they became targets for persecution because of their refusal to submit to the tyranny of the warlords and fundamentalists. As Mohammed Zahir Dulat Shahi put it: “I am human, like you and others. I wanted to do something good. I had a problem with those who make hell in my country for me.” Another common denominator was the resort to medication and the sense of hopelessness and desperation.

Aslam Kazimi was twenty when he attempted to reach Australia on the same ill-fated boat as Ali Mullaie. As a teenager, he said he faced the choice of joining one of the fundamentalist organisations in Afghanistan and killing others, or fleeing. He chose the latter. “If I wasn’t here, I would be a warlord,” he said. His father had been murdered and he was not sure of the fate of other members of his family, including a young wife. Like so many others, he was taking tablets to help him sleep and despaired about his future. “I forgot everything. There is nothing left for me.”

He wrote of the desperation of those in the camp in a letter to the regional representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Neill Wright, who was due to visit the camp the following day: “As you can see here and this miserable situations by the eyes of your heart we have been living here for years and it is really unbearable for every individual of us in which I and my friends faced anxiety, frustration and another physical or mental illness. Every night I deny going to my bed due to the horrendous nightmares and everyday I feel confused and have too much headache in which I’m thinking that my head is going to burst.”

Ali Rezaee was the youngest of the single Afghan men in the camp. He was seventeen when his life in offshore detention began and confessed that often, when he became consumed by despair, he would go to a corner of the camp and cry at the sky. “I’m thinking, where are my family? Where are they now? What are they feeling now? They might think that I am dead. They think that they have lost me.”

A few months before my visit, Rezaee had expressed his feeling of helplessness in an email to Halinka Rubin, a Polish-born Holocaust survivor living in Melbourne who was a tireless supporter of those on Nauru and in mainland detention. “I was a leaf fallen down from a tree, I have no home, no shelter,” the email began. It included these lines:

I am a boy who is powerless and lonely burning inside the fence,

I am a boy who is solitary has been grabbing with discrimination in the circle of human being.

I am a boy whose brain is full of sorrow. I am a boy whose body is full of wound feeling of pain, doesn’t have rest for awhile.

I am a boy, who just sees dark and dark, and a minute is passing like one hour, a month is passing like a year. And have no sleep without tablet, no medicine available for reducing the pain, except rolling tear on my cheek.

I am a boy who in the mid of night, most of the time lonely sitting in the corner side the fence, looking at blue sky, at stars, weeping tears, during that time none is moving around.

ARIF RUHANI, who I spoke to next, was also rejected on the basis that he was from Pakistan. He said his cousin and others in Australia had written letters confirming he was from Afghanistan, but he had heard nothing from the department about whether his case was being reviewed. Ruhani explained that his darkest hours were often after others had been accepted and that he had been sustained by the support of Australian friends. While Ali Mullaie kept himself busy helping the Nauruans, Ruhani focused on the others in the camp. “Whenever my friends need me, I show them how to use the computer. Those who cannot write letters for their friends, I write letters for them.”

Assadullah Qazikhil’s was a different story from those of the others who claimed to be Afghans. He was a military officer in the pre-Taliban regime, but insisted he was not a criminal and had never used a gun against his own people or any others. “I am asking the Australian government to investigate my case,” he told me. “If I am not telling the truth, if I was liar, they can put me in a charter plane or anything and they can throw me in Afghanistan without any problem. But first I would like them to investigate whether I am right or wrong.”

When I asked why he did not take up the Howard government’s offer to return to Afghanistan, his response was compelling. “Imagine, a father of six children and the husband of a beautiful wife? Of course, you would go back if it was safe,” he said, later returning to show me a picture of his wife and children.

Then there was Arif Hussaini, who seemed one of the most troubled of those in the camp. “The thing he wants to tell you is that there was a misunderstanding in his case,” explained Ali Mullaie, who interpreted his words. “He was mistaken for another person with a similar name. The interviewing officer told him names of sister, brothers, father and mother and the name of the place he was living and it was all wrong.” Hussaini told the case officer he had the wrong person, but his case was rejected. He did not know whether the mistake had been recognised and said he could prove his identity and Afghan nationality. “He is thinking there is nothing for him in this world,” said Mullaie. “There’s no help for him. Only he is getting the tablet for sleeping. Every night he is going to the nurse and taking the tablet for sleeping.”

Mullaie was interpreter for two of the other inmates. Qurban Ali Changizi, twenty-five, was another who insisted he had been wrongly deemed to be from Pakistan. “The Afghan embassy can prove he is from Afghanistan. All of his family is there: father, mother, sisters, brothers,” said Mullaie. “He left Afghanistan because his life endangered. He needs help. He is young and he is tired of waiting here. It is too long in this detention centre. How is it that thousands of refugees from Afghanistan are living in Australia and twenty-nine people from Afghanistan are left here and rejected? It’s not fair.”

Ali Jan Jafari was another who seemed lost and withdrawn. “I was twenty-one, but now I’m twenty-four,” he said through Mullaie. “He wants to tell the people of Australia that day by day he is losing his mind.” Jafari’s parents were dead and his only brother had also left Afghanistan, but he had no idea where he was. “He has psychological problem and taking tablets and it is not helping him.” Recently Jafari had stepped in front of a car during day leave from the camp and was pulled clear by one of his friends. “His mind is not working,” said Mullaie.

In all, my eighteen interviews covered thirty of the camp’s fifty-two inmates, including two young Iraqis who were awaiting decisions some seven months after having been reassessed. When, finally, there was no one waiting at my door, I went with Mullaie to his small room, made even cosier because he had inherited a desk and bookshelf from those who had won freedom in Australia and New Zealand. Yes, he said, he would still like to go to Australia. “I’d like to say thank you face-to-face to the people who are helping us, to show them that the person writing to you is not different [from the real person].” Unlike many, perhaps most, of the residents, he chose not to take sleeping tablets. When he could not sleep, he wrote poems in Dari and then translated them into English. After his rejection, he wrote:

I shouted and no one heard my cries,

The universe laughs at my cries,

This load has broken my back,

Every joint in the body is cracking.

In his darker moments, Mullaie feared he had been penalised for trying so hard to improve himself in his years on Nauru. In one email to Marion Le, he noted how an interviewing officer looked surprised at his neat handwriting and appearance (he went to the interview in his school teacher’s uniform). “In Afghanistan I did not have the opportunity to educate myself because of bad circumstances, so when I came to Nauru Camp, I got the opportunity,” he wrote to Marion Le. “I felt happy and lucky that I could use my time and the facilities in the Camp and could make myself a smart person in this almost three years. It is a real pity that with all my efforts to gain knowledge and be rejected.”

Certificates he kept in his room confirmed his completion of IOM courses in electronics and teacher training. Letters from Nauru College testified to his “kind assistance,” his expertise as a computer teacher and his willingness to “offer his services for the benefit of the children.” But it was little comfort.

The light was fading when I left his room. Some of the asylum seekers were playing volleyball. Several returned to the camp ahead of the curfew and wanted to tell their stories. It was too late. As I prepared to leave I was approached by one young Iraqi man with reddened eyes and a desperate expression. He was taking three sleeping tablets each day, he explained, but still could not sleep or find any relief from his sense of hopelessness. All I could offer was my hand and my sympathy.

When I left the camp, I felt the need to talk to someone about what I’d seen and heard. It had been an emotional experience. Instead, it was back to the Oden Aiwo for satay beef, minus the satay sauce, and a can of Victoria Bitter in an empty dining room.

THE NEXT morning was my last on the island. Before visiting Nauru College to observe Ali Mullaie in the classroom, I called by Nauru’s biggest retail and import operation, Capelle & Partner, and briefly talked to its general manager, Sean Oppenheimer. He supported the efforts of the new government to get Nauru’s affairs in order and, like many Nauruans, his perspective on the camp was purely economic. More than eighty locals were employed and their wages were among the highest on the island and supported many extended families. He was hoping for a return to the same sort of numbers – around 1200 asylum seekers – that were there at the peak. “It was good for business. It was good for everybody.”

At the school, the power was off, presenting a considerable challenge for those learning computer studies. Although Mullaie was designated as a support teacher, the young woman in charge of the class had deferred to his knowledge and communication skills and he was taking the class. With no electricity, he used the battery-powered computer sent to him by an Australian family to explain desktop publishing to the students. His aim was that, by year 7, his students would be able to design a website. So engrossed were his students that, despite the sweltering heat and lack of air in the classroom, no one moved when the bell signalled playtime. It was another ten minutes before he realised the time and called the lesson to a halt.

The principal of the college, Floria Detabene, told me that at the education workshop there had been times when Mullaie would show his sadness. “He used to become very pale and we’d know he’d be stressing out and psychologically feeling down, but as the years go by, I think because we made him feel at home, he started improving.”

His approach was to keep bad thoughts at bay by staying busy, he told me. “When I’m doing positive things, good things, it brings peace to my heart. When I’m not teaching, I’m preparing myself and learning some more and making myself ready for next time.” But there were times when Mullaie locked himself in his room and cried. It was only after he walked me to my car during recess that he confided to me that, like many of the others, he was very close to giving up. I gave him a hug to say goodbye and, for just a few seconds, he clung to me, a vulnerable young man with an uncertain future.

MY PROFILE of Ali Mullaie and accounts of my interviews with other camp residents appeared in the Age and the Sydney Morning Herald on Saturday 16 April 2005. Under the heading “Nauru’s Forgotten Faces of Despair,” the Age’s front page featured photographs showing the faces of fourteen of those I had written about. Over the next few days, in the letters pages of both papers, readers expressed their dismay and outrage over the government’s treatment of those on Nauru and their admiration for Mullaie and the others. Many of those who wrote were people who had offered comfort and support to the asylum seekers by correspondence over long periods. Some of those who responded appeared to have been touched for the first time by the consequences of John Howard’s border protection policy.

A few weeks later, in late May, I was watching Saturday school football when a call came from Marion Le. Nine of the Nauru asylum seekers had been told their claims were now accepted. Ali Mullaie was among them. So, too, were the Hussaini family, Ali Rezaee, Arif Ruhani, Aslam Kazimi and Zahir Dulat Shahi. Once again, the Nauru camp was the setting for extremes of happiness and sorrow as some received the news they had been awaiting for almost four years and others dealt with feelings of rejection and even the prospect of forced return. •