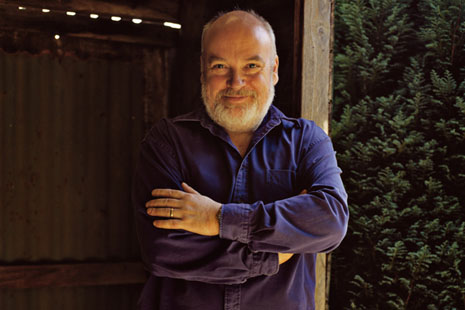

YOU’LL KNOW Andrew Ford if you’re a fan of The Music Show on ABC Radio National, where he discusses an amazing range of music and talks to an amazing range of musicians. The title of his most recent collection of interviews, Talking to Kinky and Karlheinz, says it all; Ford is genuinely enthusiastic and knowledgeable about all the music he discusses, be it that of Texas’ only Jewish cowboy or the late Meister of the German avant-garde. He has also broadcast important radio series, among them Dots on the Landscape (available as streamed audio from ABC Classic FM’s website) which is an invaluable oral history of Australian music. He has published a book of interviews, Composer to Composer, a study of Van Morrison (co-authored by Martin Buzacott), and the heartfelt In Defence of Classical Music. But as he would point out, the writing and broadcasting is part of his principal vocation, which is as a composer – and a prolific one at that.

Like another expatriate composer, Roger Smalley, who arrived in Perth a decade earlier, Ford was born and educated in Britain and came to Australia to take up an academic position – in his case, at the University of Wollongong in 1983. And, as in Smalley’s case, it is fair to say that being in Australia caused the composer’s work to take a direction he might not have foreseen. It is not that Ford or Smalley became any more “conservative” than they might have been had they stayed in the UK. But conditions such as the number and nature of opportunities and the size and expectations of audiences here are different. It’s not just that there are fewer concerts or more conservative audiences: in fact, as Roger Smalley found in Perth, the difference is partly that Australian audiences were more generalist, going to everything on offer be it baroque or Birtwistle. The emphasis is different, and, inevitably, so is the music.

The sources of Ford’s work are as varied as the guests he profiles each Saturday morning. His vocal music sets texts by, for instance, Christina Rossetti, Thomas Campion, Goethe, St John of the Cross, A.D. Hope and Sappho (that’s just the text for one work) or Malay, Finnish and Pueblo Indian folk poetry (that’s for one other). His interest in language has made him a prolific composer of music-theatre works, ranging from pieces written for young performers through to adult concepts like the monodramas Night and Dreams, about Sigmund Freud, Casanova Confined or Whispers, in which a conductor experiences mental collapse while rehearsing Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. There are larger-scale operas too, such as Poe and Rembrandt’s Wife. The visual arts are another major source of inspiration. In his Manhattan Epiphanies, a set of stand-alone works composed for the seventeen solo strings of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Ford responds with musical analogues to the creative techniques in artworks by Rothko, Cornell and Motherwell; a number of other pieces celebrate the works of Mondrian and Brueghel.

Ford’s greatest inspiration comes, however, from music itself and this is reflected in a generous eclecticism. His Piano Concerto: Imaginings alludes to the Mersey sound of the popular music in Ford’s native Liverpool; Whispers, as we have noted, fades in and out of Mahler. But a further influence runs like a thread through much of Ford’s music: that of folk song. As he has noted, in 1985:

“When I was commissioned by a British music-theatre company to write an evening-long work that would draw on the earliest recollections – including musical recollections – of elderly people living in the Yorkshire Dales, I was surprised to discover memories of the folk songs I’d known as a child coming back to me very strongly. Added to this was a new awareness, on my part, of a tradition of fiddling still relatively healthy in parts of the Dales. At least it was in 1985.”

The music-theatre work was Hand to Mouth, a relatively site-specific piece, but three tunes from it found their way into On Canaan’s Happier Shore, composed for Elision in 1987. In this work, as in subsequent ones, the folk material isn’t merely quoted and “set”: it forms the basis for abstracted development. Ford took this a step further in Pastoral for string octet, where the instrumental figurations owe much to, but do not merely replicate, traditional fiddling styles. In Dance Maze, similarly, the metres and rhythms of dance create a sense of something half remembered, of dancers lifting heavy feet in clumsy shoes. The echoes of folk styles reverberate in works like Tales of the Supernatural, in both the string writing and the construction of melodies. In his concerto for viola and chamber orchestra, The Unquiet Grave, Ford gradually reassembles a classic English folk song.

Until quite recently anything that resembled the work of “English pastoral” composers – say, Vaughan Williams or Butterworth – was regarded as irredeemably retro nostalgia. Australian composers such as Robert Hughes (1912–2007) or Clive Douglas (1903–1977) whose music retained traces of a British accent were, from the 1970s on, seen as a symptom of the cultural cringe to be laughed off the stage by real modernists. Thankfully, the conversation about “Australian” music has finished with narrow notions of nationality and it is a sign of some maturity that this material is now available without the cultural baggage. In this context, it is worth noting that Ford’s Dance Maze received its premiere performance abroad: Australian music can easily embrace a British-born composer using English folk material for a work to be premiered in the United States.

“The Unquiet Grave” is a folk tune that was collected in 1868, well before the English folk-song revival spearheaded by Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst and, indeed, Percy Grainger. (It is also the title of a book of wartime meditations by Cyril Connolly about “the core of melancholy and guilt that works destruction on us from within,” which Ford had read at about the time he began composing the work.) The ballad tells the story of a young man whose lover has been slain in the forest and whom he (though the roles can of course be reversed) mourns “for a twelve-month and a day.” After this time the ghost of his dead love arises, pointing out that his grief is preventing her from resting in peace. She tells him that to kiss him now would kill him, but that they will meet again “when the autumn leaves that fall from the trees/ are green and spring up again.”

Like Benjamin Britten in a number of works based on existing melodies, Ford contrives to save a full statement of the tune until the end, a reversal of the classical pattern of “theme and variations.” The experience of the piece is a process of discovering something, piecing together fragments of the tune, or seeing its contour flattened or expanded according to the prevailing mood. The Unquiet Grave does not seek to replicate the events of the poem in any programmatic way, but its orchestration evokes the shivering cold, and the extreme emotional states of the ballad’s singer. These range from the bleak melancholy of the opening, through nostalgic reminiscence and smudged outbursts of frank anger. We might “hear” the voice of the ghost in some of the viola writing, and even see the eventual statement of the tune as the attainment of calm acceptance, if not comfort.

Ford’s concerto is scored for solo viola and a mixed ensemble of fourteen instruments including saxophone (soprano and alto), which blends admirably with the viola. A three-note (E flat-G-F) motif, drawn from the folk tune, opens the piece. Winds and trumpet mask the beginning of the horn’s long E flat with a dry staccato – not hearing the attack of a note affects how we perceive its tone quality; it can make it initially difficult to recognise the instrument playing, giving the sound a literally disembodied quality. Over the horn, tubular bells and harp provide the remaining G–F, the latter note left hanging like a faint echo as a double bass harmonic. Other strings add harmonics to create a cold, misty chord, as the soloist begins with a motif that gradually widens out from knotted semitones and tones to fifths, sixths and a falling minor ninth, like watching a flower unfold in time-lapse photography. In this way Ford establishes the icy sound-world and emotional temperature of the piece.

The viola’s journey through this landscape encompasses extremes – long and soulful melodies, an almost silent wailing of harmonics far above the texture. A new section has leaping disjunct patterns, echoed by the alto saxophone, while the orchestral viola sings a wide-ranging melody; the solo part becomes more angular with hacking double- and triple-stopped fragments that break eventually into liquid sextuplet lines.

At one climactic moment the viola’s high expansive melody is doubled at pitch by repeated sextuplets on vibraphone, adding a throbbing vibrancy to the sound. Soon swirling string figures and harp glissandos sound before the downbeat of each new bar; the viola finally reaches the F above the treble stave – the viola’s sound here is necessarily tense, requiring a lot of pressure and control from the player’s left hand. The tension shatters the music into fragments: pizzicato quavers, staccato writing for flute, oboe and harp, short dry cluster chords from trumpet, horn and vibraphone. The viola returns to earth with heavy bowing in its lowest register, effortfully rising again against static wind writing and taking the viola back to its highest extremes. In the following cadenza the viola shudders with ghostly sul ponticello (near the bridge) bowing. A single note from the horn tries to bring the music back to reality – we expect the bell to answer as at the start, but only a brusque staccato chord, sounded three times by the harp, releases the glacial string chords and a melody on piccolo derived from the viola’s very first motif.

The horn, bell and harp gesture returns at double speed; a frenzied passage dominated by fretful repeated notes in the horn and trumpet and surging, microtonal thrusts from the strings presents a musical image of hysterical grief. In the hollow space left by the inevitable collapse, supported only by a double bass harmonic and soft, slow-moving lines from the brass and wind, the viola quietly sings phrases from the original tune (the score includes the words: “Cold blows the wind to my true love, and gently drops the rain. I never had but one true love, and in the greenwood she lies slain”). The effect is a little like that described by Emily Dickinson in poem 341: “After great pain, a formal feeling comes/ the nerves sit ceremonious like tombs.” The work ends as the melody unfolds, against gently falling scalar figures in the winds, and a soft string chord which implies, perhaps, G minor.

The Unquiet Grave is dedicated to the memory of British composer Michael Tippett who died around the time of the work’s composition. Ford has approvingly quoted Tippett’s desire to create “images of reconciliation for worlds torn by division. And in an age of mediocrity and shattered dreams, images of abounding, generous, exuberant beauty.” He has done just that in this work. •