“The heat,” says the sweaty Border Force official in Darwin, as if it explains all his problems. He’s on the government payroll in this tropical garrison town instead of comfortably cool down south in Melbourne where he belongs, where hail is predicted for the big horse race running this week. “Out of all the places you could go, why did you choose East Timor?” he asks, scanning our passports and our eyeballs, keeping Australia safe.

“Tourism,” replies Claire. It’s the only answer.

“It’s close,” I add. The flight to Dili is fifty minutes. Why does he need to know?

The plane is near empty, ferrying workers, students and a few functionaries back across the Timor Sea. Immigration at the Timor-Leste end is little more than a stall on the tarmac and a form to be completed in triplicate. The top copy dropped in a tray and we’re through. The guide we’ve been texting greets us in the arrivals hall with the news that he’s leaving in the morning for Honolulu on a tourism training program sponsored by the UN but has found us a replacement, Basilio, who leads us away to the carpark. Basilio is a young man with a family; the Suzuki Swift is the family car.

Into town the road follows the strip of land between coast and mountains, taking us past the new Tibar Bay container port, built by a French company with Chinese contractors, and the site of a luxury resort under construction with Singaporean money. In the distance the rugged skyline notches down in the profile of the mythic crocodile that protects this island and its people.

We stop at a shopping mall downtown for local sim cards, waiting in line with our US dollars, the currency here. There’s more paperwork than at the airport. Then Basilio drops us at the hotel. Fans chug overhead in the cavernous lobby. It’s like a Portuguese pousada, with teak beams and a wide staircase to the upper floors. A trio of Peranakan Chinese women sitting in low armchairs tinkle their gold bangles as they negotiate with a pair of nervously grinning male officials.

It’s getting late. We’ll head out in the morning.

Our visit from Darwin has been set up by translator Lurdes Pires, who was a producer on Timor-Leste’s first feature film, Beatriz’s War, in 2013. Dramatising the experience of women during the long years of Indonesian occupation, it averts its gaze neither from the sexual violence nor from the anguish of accommodation and survival afterwards. The mostly non-professional performers re-enact what happened in the locations where it happened, speaking and singing in their own language, Tetun. It’s a cathartic story of haunted return.

Pires’s most recent film is a documentary called Circle of Silence (2023) about Shirley Shackleton, widow of Greg Shackleton, one of the five television journalists from Australia murdered by the Indonesian military in the lead-up to the invasion. The film shows Shirley Shackleton’s lifelong quest not only to find out how and why those young men died at Balibo in 1975 and what happened to their remains, but also to expose Australia’s complicity in the Indonesian annexation of the former Portuguese colony.

In 1975 Lurdes, aged fifteen, was evacuated to Darwin with her family. In Circle of Silence she appears on camera interviewing her former classmates, including a woman who had married a former Indonesian soldier. Half a century later, as a retired general, the same man helped run Prabowo Subianto’s recent presidential campaign. Son-in-law of Suharto, Prabowo was a high-ranking officer in Indonesia’s special forces, Kopassus, during the occupation of East Timor. Since sanctioned for human rights abuses, he is now president elect.

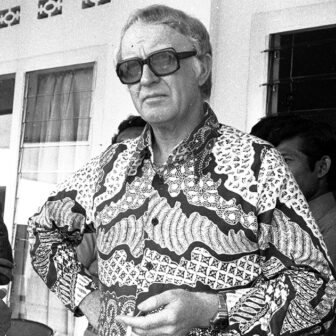

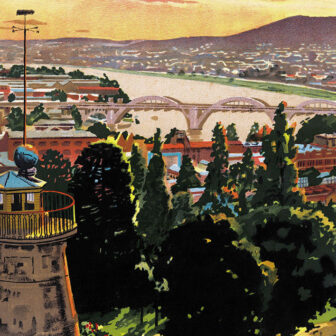

Balibo memorial: the Australian journalists’ flag, hand-painted in 1975. Claire Roberts

In an extraordinary scene in Circle of Silence, Lurdes is filmed in a Jakarta hotel meeting with her former classmate while separate audio of their conversation, a phone recording, plays over. In 1975 the East Timorese woman’s Indonesian husband, Yunus Yosfiah, had opened fire on the five journalists from Australia as they were attempting to surrender.

“The wet” says Lurdes, meaning this can be a bad time of year to travel. The roads are terrible; the weather is hot and humid; it rains every day. But the country is also at its most beautiful, lush and green, with flowers blooming and trees fruiting. People are happy, returning to their villages for the holidays when festivals and ceremonies happen.

Tourism in post-conflict Timor-Leste is bound up with past conflict in ways that Basilio is trying to understand. First stop on the road to Balibo is the site along the coast where Pope John Paul II celebrated mass on his visit to the island in 1989: a site previously used for political executions. The Pope’s visit to this small Catholic land held risks both for him and for Indonesia in that world-shaking year. Suharto had come to Dili the previous year to affirm East Timor’s future as part of Indonesia, bringing with him a replica of Rio de Janeiro’s Cristo Rey statue to be built on the headland to the city’s east. From the experience with Solidarity in his own country, the Polish pontiff had a different understanding of the church’s role in supporting the oppressed. In East Timor, the church embraced young people with its own version of liberation theology fused with indigenous animism.

Two years later, in 1991, Indonesian troops fired directly into the crowd when young pro-independence East Timorese gathered in Dili’s Santa Cruz cemetery to mourn their slain comrades. British journalist Max Stahl captured the massacre on film and smuggled it out of the country, forcing the international community to confront the atrocities being perpetrated in a part of the world otherwise off the map.

An endgame that proved no less violent and duplicitous had begun. The hastily managed referendum in 1999 showed overwhelming support for independence. Revenge killings followed and Dili was left a scorched ruin as Indonesia withdrew. A belated Australian-led UN intervention brought some order to the transition and is judged to have been a success. Thus was Timor-Leste born in 2002. Max Stahl, whose courage as a journalist played a key role, died in 2021, just short of the new nation’s twentieth anniversary.

Our road passes muddy mangrove swamps where salt is still extracted the ancient way, by boiling down brine until crystals form. A fire in a hut is fed for hours with palm fronds, a pan is skimmed of scum and white salt appears. It is sold in one kilo plastic bags that look like small pillows, pegged up at wayside stalls across the country: the salt of life, for fifty cents a bag.

Further along are paddy rice, corn and vegetable patches and an array of domestic animals — dogs, chickens, ducks, pigs, goats and an occasional pet monkey — straggling on to the unfenced road. We stop to eat rice balls steamed in banana leaves with sweetcorn, strong local coffee and ginger candy. An old Dutch fort is selling handicrafts made from woven palm leaves; its stone walls shaded by mighty camphor trees, it is a disused enclave within erstwhile Portuguese territory on the frontline of maritime defence. Soon we reach the Indonesian border. West Timor is on the other side, Koepang as it was, part of the Dutch East Indies until 1949.

Today’s border crossing has modern grills, barriers and boom gates watched by concrete guard-boxes. It’s sleepy and slow in the afternoon sun, and friendly. Basilio knows the men on duty. He can speak their language. His wife’s family lives on the West Timor side. Their two kids were stuck there with their grandparents during Covid, speaking Bahasa. Basilio — like us if we want — can cross and come back on the same day. There are things that are cheaper to buy on the Indonesian side.

Sleepy, slow and friendly: the border with West Timor. Claire Roberts

After all the death and damage, relations between tiny, Catholic, newly independent Timor-Leste and its populous, sprawling, Muslim-majority, democratising, archipelagic neighbour are closer than with anyone else. Boa viagem / Farewell says the gate at the crossing. We wave goodbye and take the winding road up to Balibo.

For Australians Balibo is a code word that inscribes the death of five young white men into the martyrology of the Fretilin resistance and the sacrifice and deprivation of hundreds and thousands of East Timorese. It is the site of an old Portuguese fort high in the mountains overlooking the coast and the hinterland.

The journalists rushed there to cover the Indonesian military’s border incursions late in 1975, during the prelude to full-scale invasion. They were warned to get out, as if somehow Australian authorities had been tipped off. They were killed to prevent them from reporting and as a warning to others. Today, Balibo House is their memorial, serving as museum, community learning centre and healthcare clinic, funded by charitable donations. Still on its wall is the Australian flag daubed by the journalists in the hope it might protect them.

Balibo is a tourist destination. Across the way is a crumbling store where the bodies of the five men may have been burnt. There’s an old monument to Pancasila, Indonesia’s five principles of reformasi, and a new shop selling Chinese household goods. The shop is run by a young woman from Fujian who is married to a local man and part of a growing Chinese trading network. Everyone needs what they sell. Another stall parades champion roosters and provides palm wine for cockfights. The ground is strewn with discarded playing cards and empty cigarette packets that carry health warnings. Impotencia!

Up the hill is the church and the cemetery where we join the All Souls procession. On this day for remembering the dead, people of all ages are dressed in their best. Girls in frilly blouses and woven tais come forward with baskets of petals — bougainvillea, frangipani, cassia — and carry candles to place at the graves. Boys on motorbikes sport deadly t-shirts, rev their engines and hang back. Wax melts from the burning candles, smoke rises, the flower petals turn to ash.

On his cell phone Basilio shows us the same ceremony happening in his home village. He waves to his wife and kids. The sounds from there and here merge in the music of this holy day. Later, after nightfall, bonfires blaze on the terrace of the Balibo Fort Hotel, keeping the mosquitoes away. The lights attract swarms of flying ants — edible, meaty. The resident tabby cat with no tail leaps to catch them.

Remembering the dead: the cemetary near Balibo. Claire Roberts

In the morning we drive up the track to a farm where a family tends its own graves according to animist custom. The fifteen-year-old daughter is learning English and speaks for the group. Most days she walks into Balibo to school, where she’s good with computer skills. She’ll get a job in town when she graduates. The family shares a hand of the bananas they grow. Toddlers clamber onto our knees and a newborn is passed around. The grandmother smiles at her family, her home, her earth, as my partner Claire, the photographer, documents the moment with the camera on her phone. Then the old woman wanders away.

What makes all these phones work? Nickel, manganese, cobalt, lithium. Where are those minerals? In this earth and in the sea, like the oil and gas long in dispute between Australia and Timor-Leste, settled belatedly in 2019 in a treaty that established the maritime boundaries in the Timor Sea.

Extraction has been this island’s fate, and its attraction, for centuries. In 1436 the Chinese traveller Fei Xin reported a flourishing trade in sandalwood. A century later the Portuguese arrived. Sandalwood, revered by Hindus and Buddhists alike for the spiritual powers of its fragrance, was traded widely through the markets of Malacca. The scent stays in sandalwood for years, making it one of the world’s most valuable timbers.

Native stocks in Timor were so relentlessly logged that by the early twentieth century they became barely sustainable. As journalist Bikash K. Bhattacharya explains, exploitation ramped up further during the Indonesian occupation, funding pro-Indonesian militias through Chinese middlemen. He quotes from a 2001 research paper: “The unremitting plunder of mature stocks has reached a point where the very viability of the species on the island is threatened.”

It’s hard to see a sandalwood tree in Timor-Leste today. When Basilio finds one in somebody’s yard it’s a small, spindly, nondescript specimen. Reafforestation efforts are underway but so far there’s not much to show. The policies put in place don’t always suit small farmers.

What happens to a tree can happen to a people. The incense burns. The smell is divine. The smoke gets in your eyes.

Basilio was born in 1987. His father, codename Felix the Cat, was a guerrilla fighter. His mother conceived a child each year when her husband returned briefly to the village from his mountain hideout; when she died in 2005, aged forty-seven, she had given birth to ten children. Basilio was somewhere in the middle.

The worst year, 1997, was during Indonesia’s last-ditch effort to eliminate the resistance. Felix the Cat was captured and tortured for information. Somehow his comrades smuggled him back to the mountains barely alive while his family staged a mock funeral in the village to convince the Indonesians he was dead. Otherwise they would have kept after him and he might have ended up in the interrogation centre in Dili, a one-way journey. It was a terrible time for ten-year-old Basilio. The teachers at his school, who had been transmigrated from Indonesia, saw such a child as the enemy. The education he got was grudging and deficient.

Later Basilio enrolled in a petrochemical engineering course, hoping for a career in that promising sector. But it didn’t work out. You needed connections. He is still looking for the best way to realise his dream of building a new house in town for himself, his wife and their two growing children. Tourism might be an option, a favoured alternative if Timor-Leste is to move on from dependency on fossil fuels. Meanwhile his father, sixty now, has retreated to a traditional house of wood and thatch in the hills above their village near Aileu, where the spirits visit.

The road south takes us past the monument to the Manufahi war, an anti-colonial uprising in 1910–12 led by a local headman. The Portuguese brought in troops from their colonies in Goa, Mozambique and Macao to suppress it. Now the event is folded into a longer history of Timor-Leste’s resistance to colonisation and eventual independence.

Up the hill at Same are the remains of a Portuguese posto or administrative station — a dormitory that became an Indonesian prison, black with mould; an abandoned colonial-era swimming pool; and a carved memorial to Indonesian troops who were ambushed and killed nearby. The solemn words in Bahasa are weathering slowly. A winged lizard lands atop the stone and Basilio laughs. He tells the story of how Falintil guerrillas disguised themselves as pro-Indonesian militia, deceiving them with smart city clothes and flash haircuts. In the distance Mount Kablake, the freedom fighters’ impenetrable redoubt, disappears into cloud.

All over Timor-Leste, Portuguese and Indonesian structures are layered over, leaving their traces in a halting present. Statues, slogans, even ways of doing things are repurposed but somehow carried forward for a new future that must both honour and transform the last century’s tragic narrative. There are new Chinese buildings wrapped around old Chinese buildings. There are Japanese and Korean aid projects. There’s the localised play of American pop culture everywhere. Half the population of the country is under twenty, born since independence.

The living and the dead: a mural at Arte Moris in Dili. Claire Roberts

In 2003 an Indonesian museum near Dili was turned into a youth arts centre where new kinds of socially engaged art and performance were encouraged. Now, twenty years later, Arte Moris (“living art”) has been evicted from the site as the current Timor-Leste government makes it over into a club for veterans like Basilio’s father when they come in from the countryside.

Those fighters must be honoured, but murals have been destroyed, artworks tipped into temporary storage and a vibrant but fragile cultural ecosystem devalued. The move has drawn the ire of the most senior veterans of all, Xanana Gusmão and José Ramos-Horta, in office again as prime minister and president respectively, after a lifetime of heroic commitment to their people’s freedom. As generations and priorities collide, no solution has yet been found for Arte Moris. Meanwhile Timor-Leste is stepping out on the international art stage with a pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the independence referendum, presenting the work of artist Maria Madeira, whose installation celebrates the resilience of East Timorese women, using traditional materials for contemporary cultural activism.

The reliance on extraction that drove a bloody history continues to drive today’s uneasy politics.

Oil exploration around the Timor Sea dates back more than a century. In the build-up to the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere in the 1930s, Japan drew up plans to access petroleum from the Indonesian archipelago in the event of war. By October 1941, just before Pearl Harbor, “longstanding moves to close off Japanese access to petroleum resources in Portuguese Timor reached fruition with a secret accord between the Australian and UK governments,” as Bernard Collaery writes in his book Oil Under Troubled Water (2020).

After the war Australian companies began exploring offshore in earnest, with seabed boundary negotiations between Australia and Indonesia underway by 1970. A “Timor Gap” — a moveable seabed feast of uncertain jurisdiction — was left between Australia and East Timor. When Indonesia invaded Portugal’s colony in 1975, Australia accepted the annexation, preferring the boundary and resource-sharing agreements with Indonesia to stand. US president Gerald Ford and his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, had visited Suharto in Jakarta on 6 December 1975 to greenlight the military action (which would use US weaponry) and were back home when it began two days later. Indonesia was regarded as an ally and a bulwark against communism.

Fast forward through five decades of disputation as oil and gas deals are thrashed out against changing geopolitics and a changing environmental consciousness. As part of the Islamic world, Indonesia found itself on the wrong side of the war on terror after the 9/11 attacks. Australia bugged the Timor-Leste government’s Dili offices in 2004 during bilateral negotiations on maritime boundaries and undersea resource–sharing, as was later revealed by one of the technicians involved.

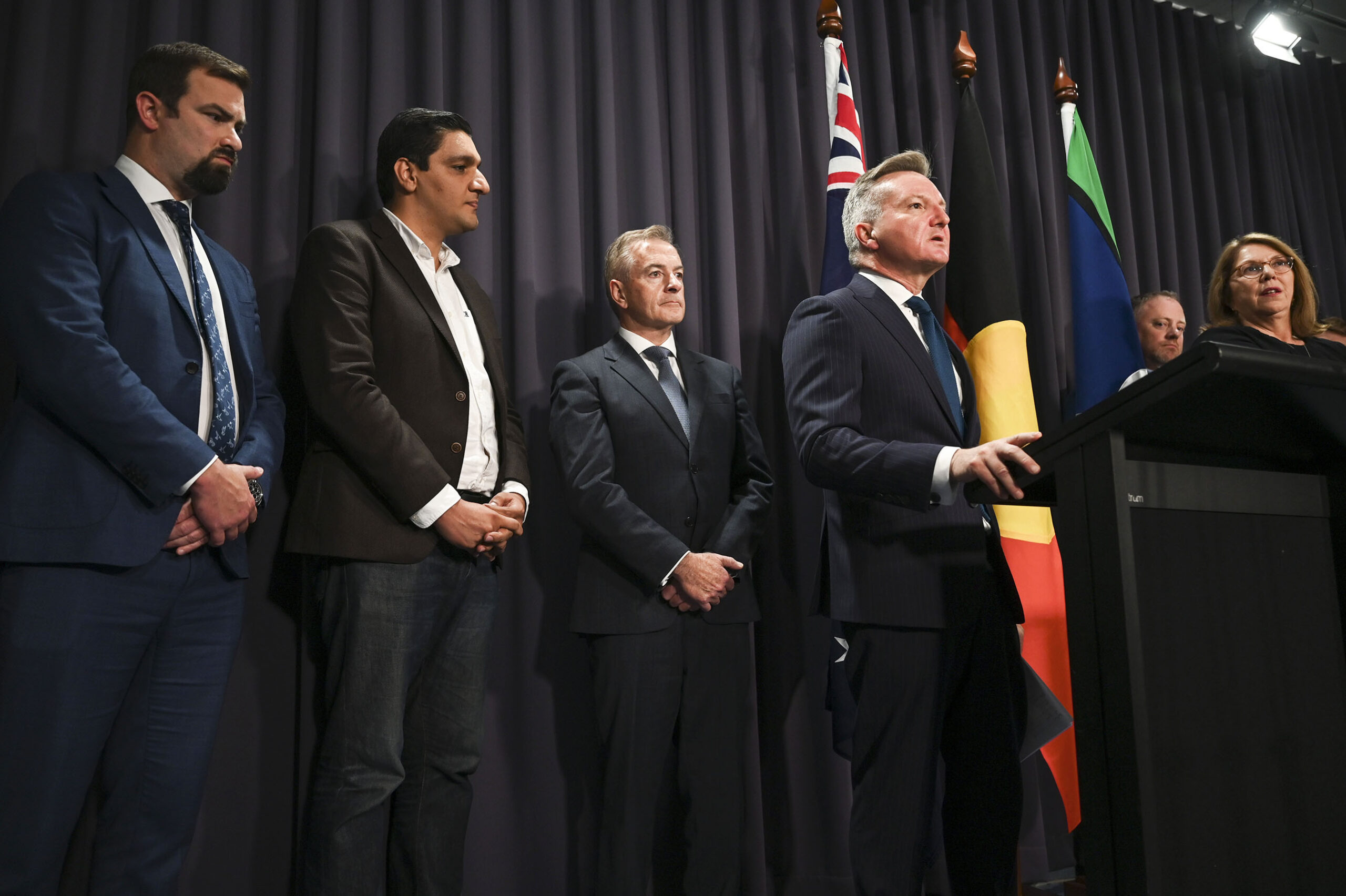

Known only as “Witness K,” the technician and his lawyer, Bernard Collaery, were charged under Australia’s National Security Information Act in 2018. After pleading guilty in a closed court, Witness K got a suspended sentence. Collaery’s prosecution was dropped following a change of government in Canberra. But not all the information concerning the matter has been released. Suspicions of skulduggery abound, some of which I conjure in my recent novel, The Idealist.

The tussle continued over Greater Sunrise, the major gas and condensate fields located roughly 450 kilometres northwest of Darwin and 150 kilometres south of Timor-Leste, now stalled by the question of where the gas should be processed. Woodside Energy, the Australian resource giant in the development partnership, has argued that the project is only economically viable if the refinery is in Darwin. Timor-Leste wants it onshore on the country’s south coast. Not only is the revenue important, with existing oil and gas income streams reaching the end of their life, so too is the location: it is a matter of sovereignty, a legacy project for the same leaders who delivered the country’s independence.

Despite fossil fuels being on the way out, fledgling Timor-Leste could benefit during the transition to green energy, including from skills transfer and infrastructure development — even if a new gas processing plant might be a white elephant in the end, and even if it means bringing China in to help with Belt and Road financing.

“For Timor-Leste, there are no allies or enemies; everyone will be only and only friends,” Gusmão said recently. China and Timor-Leste have outlined a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” Why not? China has been in the neighbourhood a long time.

A decision on Greater Sunrise is imminent. According to the partners, the aim is to identify the option that “provides the most meaningful benefit for the people of Timor-Leste.” There’s been a change of language. It sounds like a win for the old men.

And who knows what else is under the sea? Helium may be present in Greater Sunrise in large quantities, increasingly valuable for treatment of nuclear waste, medical procedures such as MRIs and defence industry needs. This and other inert gases should be included in the calculations of what Timor-Leste is owed in restitution for dodgy past deals, argues Collaery, roughly an estimated additional $5–10 billion. High-income countries with the technology to extract cobalt, nickel, manganese and the rare earths needed for EV batteries and other “clean” innovations are already racing to the Pacific’s sea floor. Deep sea mining has begun off Papua New Guinea.

Timor-Leste is an observer member of the Pacific Islands Forum that works, through its Deep Sea Minerals Project, with the International Seabed Authority to monitor and manage a rapidly evolving extractive situation. The young nation has revived a customary consensual approach to resource management called tara bandu (literally: hanging prohibition), an ecological and spiritual practice designed to enhance sustainability and community benefit in the future blue economy of this island nation.

Between the sea wall and the busy Avenue of Human Rights on Dili’s waterfront shines the refurbished Lecidere football field, the first with artificial turf in the country and a gift from China to Timor-Leste’s youth. You can’t miss its bright green under the lights. Across the bay Ataúro Island glimmers faintly in the lilac dusk. Once a prison island for troublemakers, today it’s a top diving destination.

I think of the great East Timorese writer Luis Cardoso, whose father was jailed there. Cardoso writes about his childhood on Ataúro in The Crossing, a novel translated from Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa and published in English in 2003. A fine introduction is contributed by Jill Jolliffe, the Australian journalist who kept the faith with the East Timorese people from the time she witnessed the invasion in 1975 until the end of her life in 2022.

Cardoso has a magnificent synoptic paragraph about the history of his country and the exultation of extraction at its core. Writers extract too — stories, images, analysis. In tribute to Cardoso’s work, I offer the paragraph in full:

When the Japanese entered Timor, [my father] was already supplying arms to the Australian commandos, who were engaged in an intense, uneven battle with the Japanese. The war left him with scars which he wore like medals and which, with a certain modesty, he kept covered up; he also had many stories to relate, as well as the names of the Australian soldiers he helped, names which, before his death, he bequeathed to me, urging me to claim some form of recompense. He religiously kept empty cartridge cases as trophies of war and would hang them from the ceiling of my apartment to ward off the evil eye, demons and burglars. Then, when he heard my mother humming the melancholy, monotonous songs she had learned from the soldiers of the Empire of the Rising Sun when she was held hostage by the Japanese in the village of Ulfu, he would start singing songs in English, and then it was as if the war continued in my own house, as if, in their minds, it had never really ended. All in all, more than 50,000 Timorese died, guaranteeing Portugal the continuance of its tragic colonial adventure, and guaranteeing the Australians the present sovereignty of Her Majesty the Queen. In exchange, we were left with the wreckage of a few planes on land and about the same number of rusting, battered hulks which are still rotting in the Timorese seas, giving Timor’s inhabitants something to rest their weary eyes on while they wait for help. Meanwhile, in the skies, the vultures drank toasts in champagne to the treaty that gave them the right to suck up from the high seas the mina-rai, the fat of the land: oil.

Arcing over half a century of depredation, its marks all around, Cardoso comes to rest on that key word. His concluding sentence is an ellipsis. Writing in 1997 he did not have a figure for the estimated 200,000 East Timorese who died in the resistance struggle from 1975.

Dangling his legs beside us on the sea wall as we talk, Basilio is bemused by our old person’s interest in the past. He’s full of vigour and his day is already crowded. His wife is working late, so after he has finished with us he will shop for food, go home and do the cooking, and then help the two kids with their homework. But first he wants to run up the 570 steps to the Cristo Rey statue on the headland and check out the Jesus Backside Beach below. The water is pristine. It’s a top place for snorkelling.

“Cool bananas,” says Basilio. For him it’s all future. •