JULIA Gillard’s radical departure from tradition in announcing the election date so far in advance is merely a recognition of the new reality: election campaigns are no longer the culmination, like football finals, of a political season, but are ongoing and permanent. It is no exaggeration to say that party hard heads on both sides of the fence sit down the day after an election and start planning for the next.

Once, when election campaigns had real meaning, they came after a sort of phoney war as the election cycle approached its conclusion. The real intensity began when the guessing game was over and the prime minister announced the election date, and the formal campaign started with a set-piece launch outlining the program to be put before the electorate. That process has largely fallen by the wayside, with the keynote speeches now often timed well into the campaign.

In making this week’s announcement, the prime minister spoke of the need for certainty. Implicitly, she was acknowledging a trend for parliaments to run for fixed terms. In Australia, only Queensland, Tasmania and the Commonwealth still give that discretion to the premier or prime minister.

For much of the time since federation – in twenty-five out of forty-three cases – election campaigns have been held some time in the last three months of the year. Precisely why this pattern emerged is not clear, but there are several possible explanations: the football finals were over; longer days meant it was easier to get people out at evening meetings when that was the basis of campaigning; the holiday period loomed, supposedly making people more relaxed; and the excitement of the election could be folded into the general pre-Christmas build-up.

September has usually been seen as an unfavourable month given the importance of football finals in Australia and politicians’ fears that they would come a poor second. The last September election was held in 1946, at a time of postwar relief, and Ben Chifley’s Labor government was returned. But Julia Gillard’s timing might turn out to be a clever tactic, with the opposition struggling for oxygen in the final weeks of the campaign when media coverage is intense and the information playing field is more or less level with a government in caretaker mode.

Like much in politics, of course, it is a calculated risk. The history of long campaigns is not exactly encouraging for an incumbent. So much so, in fact, that the trend for the past twenty years has been to give only the bare minimum notice as required by law –thirty-three days – which was precisely the time Malcolm Fraser allowed when he called his fateful early election in 1983. Admittedly, there were unusual circumstances prevailing, with Fraser unaware that the very same day Labor was changing its leader from Bill Hayden to Bob Hawke. It is most unlikely Fraser would have announced the date knowing he would be facing the more popular Hawke.

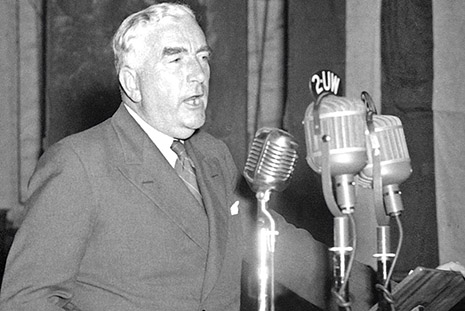

AND the longer campaigns? In 1958, a very confident Robert Menzies, nine years in office, gave three months’ notice of the election date in late November that year. A number of factors came into play, not the least being the rise of the Democratic Labor Party, which had broken away from Labor over the issue of communist influence in the trade unions. The DLP’s preferences were expected to flow heavily to the coalition, and they did. Menzies figured that the more exposure the DLP had the more effective they would be. This was also the first election in Australia to exploit television and Menzies was confident that it would show him to greater advantage than the Labor leader, Bert Evatt. He was probably right. He gained two seats from Labor, but the coalition’s vote fell slightly.

A similar tactic in 1961, with the economy in trouble after the so-called “credit squeeze,” backfired badly and Menzies came within a single seat of being defeated. This time, the extended campaign allowed the Labor leader, Arthur Calwell, to hammer away at the government’s failings. It was only the DLP vote that saved Menzies.

Fast-forward to 1984, and prime minister Bob Hawke called an early election to bring the two houses of parliament into alignment following the double dissolution of 1983. Signalling the election date some ten weeks beforehand, Hawke took much of his own party by surprise, but he was undoubtedly buoyed by a Nielsen poll in mid 1984 that showed his approval rating at a record level of more than 75 per cent.

But Hawke had miscalculated. The long campaign worked to the decided advantage of the Liberal leader, Andrew Peacock, who waged a relentless and gritty campaign. This was also the first election to feature a televised debate between the leaders, held on 26 November, just days before the 1 December poll, in which Peacock was regarded as performing strongly.

From a position of supreme confidence at the start of the protracted campaign, Labor suffered a two-point swing, and its majority went from twenty-five to sixteen in an enlarged house. The conventional wisdom was that no leader would dare to tempt fate in such a way again, and short campaigns became the norm.

But the nature of politics has changed – as has the nature of political parties, which now resemble permanent campaign organisations more than they do collections of local branches. The constant taking of the political pulse, the impact of television – and now the internet – and the advent of highly sophisticated political marketing have effectively seen the traditional political campaign go the way of the town hall meeting and the street-corner soapbox.

September, then, will be a time of decision: football premierships, the next government and Julia Gillard’s judgement. •