Sam Hood began his photographic apprenticeship in the mid 1880s, when he was barely into his teens. He was still working as a photographer on the day he died, at the age of eighty-one. That adds up to a long career, and it made for a lot of photographs, many of which can be seen on the websites of the State Library of New South Wales and the Australian National Maritime Museum, among others, and on Trove and Flickr. The State Library’s Hood archive alone – evocatively described in the catalogue as “Sydney streets, buildings, people, activities and events” – comprises some 11,400 images. This sounds like a large number, and if Sam Hood had been a painter rather than a photographer, it would have been a very large number indeed.

But photographic legacies routinely run into the tens and even the hundreds of thousands. The recently rediscovered Chicago street photographer Vivian Maier is survived by an archive of 100,000 images, saved from probable destruction by sheer chance. The photographer and photographic historian Jerry L. Thompson, in his recent polemic Why Photography Matters, tells us that the archive of Garry Winogrand, whom many would nominate as the best of all twentieth-century street photographers, runs to almost a million items, not a few of which Winogrand has never seen.

Yet archives of even these astonishing proportions can blend, unremarked or overlooked or passed over, into the vast cache of photographs already in existence, or about to be brought into existence by people whose careers are photography and by the many more people who just like taking photographs. And as we take more and more photographs, on our compact cameras and our smartphones, so we are taking less time to look at them. The contemporary photograph is no longer so much a record of the moment as a part of the moment itself, an integrated component of whatever it is we happen to be doing. Taking a photograph is something you do when you’re already doing something.

At the other end of the photographic spectrum is the singular photograph, the work of art that might hang on a gallery or a loungeroom wall. It is made with the intention of engaging us, persuading us to pause and reflect on its content, to look at it more than once, and to remember it.

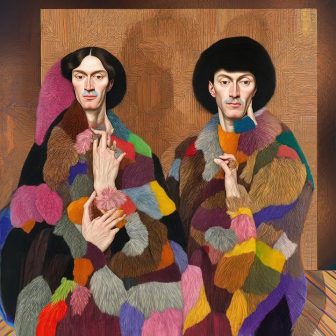

Unlike the smartphone photo, which typically favours for its subject the spontaneity (or apparent spontaneity) of the fleeting moment, the photograph-as-art will often highlight its own contrivance, by being elaborately and obviously staged, for example, or by juxtaposing people and objects in ways that emphasise the stylised formality and artificiality of the image. This kind of juxtaposition can be seen in the work of the many contemporary photographers whose elaborate “sets” and staged incongruity seem designed to distance the work from the smartphone culture and the inherent forgetability of the typical digital image.

Gymnastics on Parsley Bay beach c. 1929, photographed by Sam Hood. State Library of New South Wales

Contrivances like these are an attempt to give substance to our casual, and often misleading, habit of describing photos as “memories” by staging and photographing an event that is not part of the flow of life but a deliberate and striking intrusion into that flow, something that will be remembered for its very intrusiveness. Sometimes this can work to undeniable effect, as in Richard Renaldi’s photographs of complete strangers – strangers to him and to one another – who have been persuaded to pose in attitudes of intimacy, with arms linked or wrapped around shoulders or encircling waists, in imitation of a relationship that does not exist. It sounds faintly gimmicky but it can also produce some affecting – and memorable – images.

Not everyone would agree. Jerry Thompson, for one, has little patience with this kind of consciously artistic or staged photography. He dismisses those photos that imitate iconic paintings as “decorative self-indulgence,” for example, which seems a bit harsh, but the question he then asks is one that goes to the heart of our expectations of photography and of photographs. “Shouldn’t photography – which began as a hyperdetailed record of our shared visible world – provide a close, critical examination of that world, the kind of jarring irritant able to rouse viewers out of a complacent, forgetful slumber, and into a wakeful regard of what is?”

It is a plea for the kind of photograph that sits – perhaps somewhat uncomfortably these days – in the middle of the photographic spectrum, with the smartphone snap at one end and the photograph of complete strangers touching one another or the super-saturated tableau of people dressed up in renaissance costume, at the other. It’s the kind of photograph that manages to bring an artistic eye to the world as it is – or was, at the time when the photograph was taken. It assumes a world that can never be completely contained or managed by a photograph or a photographer, however skilled he or she may be. Chance always plays a part. “Pictures by even the greatest photographers,” observes Thompson, “insist on containing elements of the outside world that just happened to be there.”

Sam Hood was that kind of photographer – perhaps the most common kind in the history of photography – the kind who brought a photographic eye to the “world as it is.” As Alan Davies describes in his 1991 book about Sam Hood and his work, Sydney Exposures, he grasped whatever opportunities there were to take photographs and be paid for it. He photographed ships in Sydney Harbour and sold the images to sailors as mementoes of their voyage. He took studio portraits, and he supplied images to a dozen or so different newspapers in the twenties and thirties. He undertook commissions to document buildings and events – public ceremonies, sporting matches, first nights, weddings. In all this, it is doubtful that Hood ever thought of himself as an artist rather than as a working photographer whose work was his life.

Two young girls holding hands, c. 1920. Australian National Maritime Museum

And yet in many ways he behaved like an artist. He was obsessive about every aspect of photography, overseeing the entire process to ensure that the final image was as it should be. He survived many setbacks, including the prospect of reestablishing his studio after it was burnt down on two separate occasions. He pressed on, inseparable from his camera – the same one for forty years, as Davies reports, despite opportunities to upgrade. It reached a point where the camera had been repaired and patched so often, and had acquired so many tics, that “no one else could use it.”

It is difficult to know how to “read” Hood’s photographs today, just as it is difficult to know how to approach any photographic collection or archive. We are caught between our habit of scrolling through the albums on our screens – usually so quickly that it can almost be like watching a film – and the demand of the single iconic image that we pause and contemplate in isolation. But there is also a middle way. Sam Hood, and photographers like him – artisanal rather than consciously, or self-consciously, artistic – are best appreciated and understood by means of a hybrid of these two extremes, a kind of slow scrolling.

Individual photographs by Hood don’t generally stand out immediately, at least not in a way that invites us to brand them as particularly representative or “iconic,” as we might brand a Max Dupain or a David Moore, for instance. They need to be taken as a whole or, given that tens of thousands of images are difficult to take in as a whole, in chunks, further defined and refined by sub-categories of chronology or genre or subject. In this way, we can build up a sense of a particular time and place, as captured by a particular photographic sensibility.

Admittedly, not all of Hood’s photographs encourage us to scroll slowly. There are, for all but the most enthusiastic of maritime enthusiasts, only so many ships one can look at in one session. Hood also had a weakness for photographing people with animals – women with cats, men with elephants, a girl with an angora rabbit, images that fit neatly now with the web’s fascination with cuteness, but don’t encourage us to linger.

On the other hand, Hood had a special talent for observing and photographing people, and especially people in groups; sometimes in their hundreds, lined up in quasi-military formation or squashed together at a town hall hop, but more often in compositions of two to a dozen figures. The photographs are posed, reflecting the technical capacities and photographic conventions of the time, but for all that they convey a sense both of natural intimacy and of an occasion shared, while preserving the individuality of the people who make up the composition.

In the photograph of “two young girls holding hands” (above), which forms part of the Samuel J. Hood Studio Collection at the National Maritime Museum, the young girls of the caption, who are clearly twins, are posing face-on to the camera. In his characteristic way, Hood conveys naturalness within formality, individuality within likeness. The background is quite geometric – a long strip of an unidentified and unidentifiable building forms the upper border. Below that is a hedge and some vegetation, carefully clipped and tamed, that stretches across the frame. In the foreground, in contrast to these vaguely modernist horizontal lines, are the two girls, barely containing their exuberance and enjoyment of life. Most strikingly, and against the long tradition of photographing twins and look-alike siblings that owes so much to Hood’s near contemporary, the great August Sander, who emphasised likeness and encouraged the viewer to spot the subtle differences, the girls here, while dressed alike and, as far as we can guess, identical, have quite different facial expressions. They are together but also themselves.

Politicians lolling on the grass at Canberra (1927). State Library of New South Wales

The same mixture of naturalness and formality is struck in Hood’s photograph of “politicians lolling on the grass at Canberra,” taken in 1927 and now held by the State Library of New South Wales. At first and perhaps even second glance it is not an especially remarkable or distinguished photograph. And yet, in looking beyond its undoubted historical interest – the figure second from the right is the Indian politician Sir R.K. Shanmukham Chetty, who was visiting Australia as part of a Commonwealth parliamentary delegation and only a few years later became India’s representative at the League of Nations – we can see a number of Hood’s characteristic touches.

These politicians lolling on the grass of Lanyon Homestead – particularly the two in the middle – have clearly been directed, but for all that there is a relaxed if sober conviviality about the scene, and a humanising contrast between the important business that brings them together and the fact that they are sitting on the grass, chatting, staring into space, smoking a cigarette or drinking tea.

As is often the case with Hood, the background is formal, with a structured, almost geometric feel to it. The view of the verandah is divided, along classical lines, into three panels; there is even a column two-thirds of the way across to break the horizontal flow, in a way that is pleasing to the eye. In the middle panel, seated on a sofa, are two men, observing the main subject of the photograph from behind. Their presence sets up a mild visual joke, as these two rather more conventionally seated and suited figures observe their comparatively frivolous (these things are relative) colleagues lolling on the grass. The right hand panel contains a set of French doors; we can see nature reflected in the glass.

Against the formal background and complex perspective, we can also spot, to the right of the frame, a detail that seems to have crept in unnoticed: a lone briefcase and a hat, also lolling on the grass but bereft of their owner. No one is looking directly at the camera, or indeed at one another. And yet the overall impression – reinforced by the domestic touch provided by the teacups – is one of amiability and professional goodwill.

Charles Parsons & Company, 1935. State Library of New South Wales

Hood’s way with photographing groups can also be seen in an image (above) featured in Alan Davies’s monograph. It shows six men, all quite formally dressed, engaged in their work at a fabric warehouse in Sydney in 1935. The long line of a cutting desk stretches diagonally across the bottom third of the frame. In the upper background we see more long lines, in the form of rows of shelves extending into the left hand distance, each shelf piled high with neatly wrapped bolts of material that rise to the very ceiling and threaten to push their way through. In front of the shelves are the men, going about their business.

What strikes us first in this photo is that none of them is looking at any of the others. They are shown engaged in their various tasks – measuring and cutting material, making entries in a ledger. One man is retrieving a bolt of material from the top shelf. Another man – a buyer, a customer? – appears to be examining a sample. Some elements of the photograph’s composition seem to work against any suggestion of intimacy or camaraderie, and yet that is precisely what is conveyed. This impression is helped, perhaps, by the fact that on the faces of three of the men, particularly the one who is cutting material, there are signs that laughter may not be far away.

This sense of enjoyment, or ease, in one another’s company is characteristic of Hood’s group photographs. Sometimes the enjoyment and the relaxation are palpable, sometimes implied. Either way, we as viewers don’t feel as if we could enter easily into the group, becoming its next member. Instead we witness, and almost envy, its cohesiveness, which seems to spring from the kind of naturalness and lack of affectation that is difficult to replicate in these more knowing times. There is nothing “knowing” about Hood’s photographs, despite the often sophisticated nature of his compositional sense. For that reason alone, they belong quite clearly to another age.

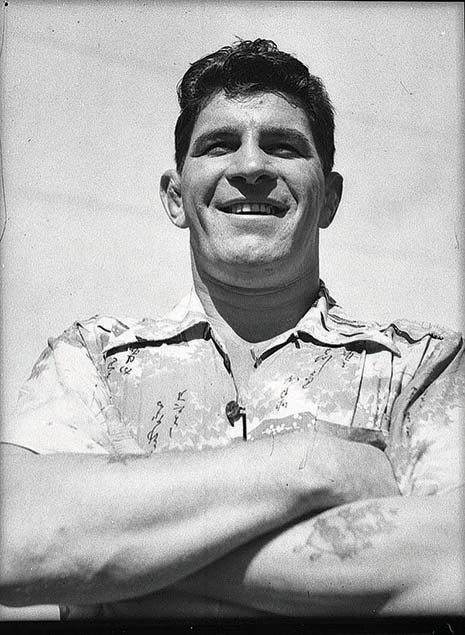

This is not simply a function of the times in which the photographs were made; old photographs can sometimes feel surprisingly contemporary. Hood’s photographs, however, do not give us a clear line to the past. If anything, they announce their pastness, if only because they come so clearly from an age in which people’s self-consciousness in posing was an essential part of their naturalness. In Hood’s world, people seem connected with each other rather than with us as viewers; groups provide consolation; individuality is downplayed. Although Hood’s portraits of individuals can sometimes express uncomplicated good cheer, as in his engaging photograph from 1938 of the wrestler Jack Gacek (below), it is also noticeable how often the individual in a single, observant portrait by Hood will seem lonely and uncertain, displaying rather less of the strength and vitality that seems to come from being photographed in company.

Jack Gacek, wrestler (1938). State Library of New South Wales

In one of Hood’s better-known photographs (below), a portrait of a woman standing in the doorway of her corner shop, the woman is almost secondary to the shop itself, which takes up most of the frame. Her stance is a combination of assertiveness and defensiveness – she has one hand on her hip; her other hand rests protectively against her neck, in a once-common social gesture that betrayed anxiety.

The inside of the shop behind her is in near darkness, while the outside, including the windows and even the footpath, is covered with hand-written signs, advertising the goods within. All this visual chatter threatens to dominate the image, quelling the figure of the woman who, despite her squared-on stance, seems in danger of being overwritten by the words that have her surrounded.

Riley & Fitzroy Streets corner grocery store, 1934. State Library of New South Wales

But if we move on, continuing to scroll slowly through the photographs of Samuel Hood, we will soon tack away from such sobering thoughts. In his group photographs in particular, Hood’s subjects appear with a kind of awkward confidence, their general optimism, and ease in one another’s company, captured by a remarkably humane and sympathetic eye. •