SOMETIMES word filters back to the intensive care unit about a patient who has died in an unexpected or unanticipated way. Nearly twenty years ago now, during a morning ward round, a trainee doctor informed us about a young woman of seventeen who suddenly died during the night while having her fractured femur (the long bone in the upper part of the leg) put in traction. Susan had been a pillion passenger on a motorbike. Her boyfriend had been killed in the same accident. Today, we would probably send such a patient straight to the operating theatre to have the femur screwed together. But Susan waited in the general ward until the orthopaedic surgeons had finished other surgery. When they did come, they were focused on the job immediately in front of them. It was late at night; they were probably tired after being on call the previous night and being in the operating theatres all day. While the orthopaedic team was putting Susan’s leg in traction in the general ward, about six hours after being admitted, she died. Her death was put down to a sudden cause: a large clot in the lung – but it was probably too early for this to have occurred; or a heart attack – but she was probably too young.

I went to her post mortem later that day. There was no obvious cause for her sudden death but the answer was in her observation chart. The nursing staff had dutifully documented over the hours since admission that her blood pressure was slowly decreasing and her pulse and respiratory rate were gradually increasing. The nursing staff had also documented that they were concerned that she was becoming drowsy. Easy to see in retrospect – she was bleeding to death under everyone’s nose. Fractures of large bones such as the femur or pelvis can result in serious but concealed blood loss; up to two or even three litres. She also had a fractured pelvis, so her total blood loss could have been four litres or even more. The average blood volume for an adult is only about five litres.

There was an irony here. We were (and are) increasingly managing older people in the last few days of life with complex machines and a vast array of drugs, while younger ones are dying potentially preventable deaths on our general wards. Over the last twenty years, studies about preventable deaths occurring in hospitals began appearing. Many of the deaths involved patients who were deteriorating over many hours. The system wasn’t working. Nurses would document the deterioration; untrained junior doctors would respond and do their best. Those trained in the management of seriously ill patients were working in their own isolated areas, such as emergency departments and intensive care units, waiting for the seriously ill to be brought to them.

As intensivists, we have become increasingly confident about our skills in keeping patients alive. We have gradually won the respect of our colleagues in the fifty or so years since intensive care units started. We have unique skills and complex machines that others don’t understand. There is even a sort of machismo around how sick our patients are and the complexity of support we offer. The greater the number of organs we support and the more complex the machinery we use to achieve that, the more legitimate and important our work appears. In the meantime, we are also exposing cracks in the general wards of hospitals, where patients fall through.

Depending on which specialty a doctor has trained in, they may have been taught resuscitation skills at some time in their career. However, the senior specialist, under whose care the patient is admitted, is usually not in the hospital at the time of the cardiac arrest. This is probably fortunate for the patient, as most specialists have not had the formal training in resuscitation up to the level of, for example, a paramedic; and even if they had, they would soon have lost those skills through lack of practice. Maintaining competence in one specialty is difficult enough but maintaining skills and keeping up to date with all the advances in acute medicine and resuscitation as well is another full-time job. Doctors have become specialised in knowledge of a single organ or in a specific population of patients, such as geriatrics or paediatrics. Other specialists who may have skills in cardiopulmonary resuscitation – or CPR, as it is commonly known – and advanced resuscitation often only operate within their own territory, such as emergency departments or intensive care units. And so it is traditional that the younger medical trainees, trained or not, perform CPR and other emergency resuscitation roles. The general wards of a modern hospital can be dangerous places if you are seriously ill. Susan had fallen between the cracks. She needed to have been resuscitated much earlier if she was to survive.

We weren’t to know it at the time, but Susan’s death in the early 1980s coincided with a new way of managing the seriously ill in all parts of the hospital, especially the general wards. As a result of her death, we have established ways of identifying those at risk, using simple measurements such as the pulse rate and blood pressure, which had so accurately defined Susan’s last few hours of life. Instead of waiting until the patient died or had a cardiac arrest, the nursing staff became empowered to call the cardiac arrest team earlier, when there was still hope of a good outcome.

Few activities are so strongly associated with the image of modern medicine than the cardiac arrest team in action: young doctors with serious looks on their faces and a sense of urgency in their manner, racing around the hospital, looking and feeling important. They are in the business of saving lives. Someone’s heart has stopped and they have only minutes to get it restarted. The brain is the first organ to die, and some damage is already occurring after about three minutes. The nurse who found the body should have already started some form of CPR. The nurse is doing his or her best, but anxiously waiting for the experts and for the instruction – “Thanks nurse, you can stand aside now.”

Of all the rites of passage in becoming a doctor, there are few more exciting moments than being part of your first cardiac arrest team. You usually aren’t allowed to do anything on your first call, which is just as well, because, while you have had about the same basic training in CPR as a boy scout, you have had precious little training in the more complex areas of resuscitation, such as securing the airway with a tube in the windpipe, inserting a catheter into a large vein in the neck or chest, connecting the patient to a ventilator, knowing how to adjust the ventilator, and being familiar with all the life-saving drugs.

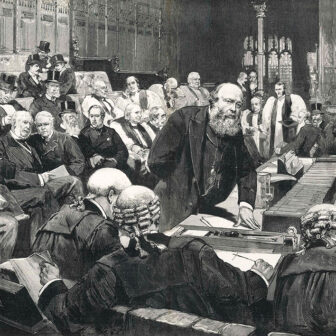

HOW DID the concept of resuscitation come about? Up until the late eighteenth century the church frowned on mortals interfering with death and dying. Only the creator could give or take life. Most of the early attempts to restore life were for the nearly drowned. A Society for Resuscitating the Drowned was established in Holland in 1767. Soon after, in Britain, a Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned was established by the Royal Humane Society for the Apparently Dead. Apart from possibly providing material for Monty Python sketches 200 years later, the words describing these societies and their aims were carefully chosen to avoid upsetting the church. For example, the use of the word humane to describe their society was a public relations coup. They were at pains to emphasise that they were not interfering with God’s work and that, in fact, it was a Christian act to rekindle the flame of a recently extinguished taper, as opposed to bringing a corpse back to life after the spark was totally extinct. The word resuscitation was deliberately used, implying reviving temporarily dead people, as opposed to reanimation, which implied raising the dead. To emphasise this point, the Royal Humane Society stated in its report of 1809 that, “in any case, resuscitation did not work after putrefaction had set in”! Now medicine could legitimately begin the business of reviving the dead – once they had been deemed only temporarily dead. Early interventions included administering tobacco smoke rectally, rolling the body over a barrel, suspending the person by their heels and tickling the throat with a feather.

Even if there was a fraction of logic in some of these techniques, people would concentrate on the odd successful revival rather than the almost universal failure of resuscitation attempts. In that regard, little has changed; the tyranny of the anecdote often still governs medical practice. It’s better to be seen to be doing something rather than helplessly standing by.

The twentieth century saw further developments which were, at least, aimed at getting air in and out of the lungs of someone apparently dead. When breathing ceased, as in the case of drowning, these techniques were tried. If, however, the cause of death was due to the heart suddenly stopping, as a result of electrocution or a heart attack for example, it’s hard to imagine any technique aimed at restoring breathing would start a stopped heart.

Techniques aimed at moving air in and out of the chest, such as Schafer, Silvester and Holger-Nielson, were being taught as first aid to many community groups up until the mid 1960s. There were strong proponents for each one, especially for the Silvester and Schafer techniques, which vied with each other before the second world war. The Schafer technique was frowned on by many more modest people as it involved straddling the patient’s pelvic region and pushing downwards on the chest, while the Silvester operators, in a more genteel fashion, knelt at the patient’s head and pulled their arms up towards the operator. The Holger-Nielson technique gradually replaced other techniques after the second world war.

It is difficult to understand how anyone survived the use of any of these techniques, as it was clearly demonstrated in the late 1950s that we had all forgotten about adequately clearing the airway. There were notional recommendations about retrieving a swallowed tongue and clearing foreign matter from the back of the mouth but they weren’t very effective. No matter how much pumping and pushing went on, no air was going to enter the lungs unless the airway was clear, and almost no air entered the lungs with any of these three techniques. What we weren’t aware of then was that to overcome the problem of the tongue falling back and obstructing the airway in unconscious patients, the jaw needed to be lifted forward. Spouses sleeping next to snorers – who have partially obstructed airways, because they are partially unconscious – know that their partner needs to be turned on their side and sometimes to have their jaw lifted in order to stop the snoring.

We were about to stumble on a technique that was simple, effective and based on sound physiology. Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation had been reported at least a century before the 1950s but was now shown to inflate the lungs much more efficiently than the Silvester, Schafer and Holger-Nielson techniques. By lifting the jaw forward, air actually entered the lungs. This was proven in medical students paralysed by drugs, in the days before ethical permission was required for research. In students assigned to the Holger-Nielson technique, there was a severe depletion of oxygen, to the extent that the students nearly had cardiac arrests, compared to the medical students assigned to the group having the newly developed mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

The next challenge was to get the heart going. During experimentation with defibrillators on the chest wall of anaesthetised dogs, the same researchers who had developed the jaw thrust and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation noticed that intermittent application of pressure on the defibrillator maintained the pulse and blood pressure of the dogs. This led to the use of external cardiac massage, which became the third and final part of CPR, now commonly known as airway, breathing and circulation or ABC. We now had a technique that could, in theory, maintain the basic functions of life by keeping the heart and lungs working. This is enough to keep otherwise dead people alive until more definitive treatment can occur.

LIKE MOST medical advances, it took some time to take off. An interesting study was published demonstrating the successful use of CPR in patients. These were otherwise healthy people having surgery, whose hearts had stopped and were restarted with CPR. The circumstances in which the arrests occurred were somewhat overlooked and remain so to this day. The report was made at a time when anaesthetics could be dangerous and sudden deaths were not uncommon. Successfully resuscitating these patients was not the same as reviving patients who had bled to death or whose heart had worn out as a result of old age. Nevertheless, the CPR industry was born and quickly ran out of control.

Initially, doctors were reluctant to share CPR with the community. After all, saving lives in such a miraculous way was a medical matter. The American Heart Association argued that CPR, especially cardiac massage, was a medical procedure. This didn’t make sense, as a layperson was far more likely to witness an out-of hospital cardiac arrest than a physician passing by. By 1970, however, community awareness and training in CPR had become commonplace, and by 1990 the technique had become thoroughly embedded in the community with widespread education and compulsory posters in places such as public swimming pools. Laypeople who have completed a CPR course can now perform the procedure as well as, if not better than, most newly qualified medical students.

The concept of CPR led to several other important developments. The application of the technique is usually not life saving in its own right. It maintains basic functions of life until definitive treatment can be delivered, including defibrillation, artificial ventilation or administration of drugs. These techniques usually require someone with medical training. And so the first ambulances with medical personnel were established, allowing rapid medical attention on the scene, as soon as possible after someone from the community had commenced CPR. Trained ambulance personnel or paramedics could do most things as well as, and in most cases better than, a doctor, and were used to working in environments more chaotic and difficult than a hospital emergency department.

Apart from the odd electrocution or drowning, CPR was increasingly being used for people in the community who died after having a heart attack. There are many ways this can occur, but the two most common are, firstly, that the heart can just stop working because of the sudden lack of a blood supply, as a result of an artery supplying the heart suddenly blocking (a so-called coronary occlusion); secondly, the heart can fibrillate instead of efficiently pumping blood, usually also as a result of insufficient blood supply. CPR can be effective in both situations, but it is much easier to restart a fibrillating heart with electrical shocks applied to the chest wall (or defibrillation) than it is to restart a heart that has just stopped stone-dead. Defibrillation, when available, has become an integral part of CPR. In fact, most authorities now suggest that defibrillation, when immediately available, should be applied before CPR. In some countries these defibrillators are freely available at railway stations, airports and even casinos.

Even if performed optimally, CPR after the heart has stopped is often not successful in restoring life. After their first few cardiac arrest calls, medical trainees intuitively begin to understand that CPR is usually a “last rites” ritual – a continuation of the focus of modern medicine on doing everything possible to restore and sustain life. Only about 15 per cent of patients requiring CPR in a hospital and approximately 1 per cent of patients who have arrested in the community and had CPR survive to leave hospital. And this dismal figure hasn’t changed since CPR was first introduced in about 1960. Moreover, these figures do not give any indication of what state the survivors are in. Many are in a coma or have severe brain damage. This is not the impression we get from medical programs on television, where success rates appear to be around 70 per cent.

How did such a poorly proven intervention become a routine end to many people’s lives? While there are many articles about the anecdotal success of CPR, there are few extensive studies putting the success stories in the context of, for example, which groups of patients CPR is more effective in reviving. It is estimated that providing a hospital CPR service costs approximately $450,000 per survivor, making it one of the most expensive procedures in medicine.

On the other hand, large research departments all around the world spend millions on determining the most effective number of chest compressions and artificial breaths that should be applied per minute; and whether drugs be given intravenously or directly into the heart; and what drugs and at what doses these drugs should be given. Thousands of dogs and other animals are sacrificed in these experiments.

Even for the approximate 15 per cent of patients who survive to leave hospital, we know little about the eventual state of those survivors, nor about the ones who didn’t leave hospital. Were they left on ventilators or discharged in a vegetative state to some kind of institution? The CPR industry has moved a long way and is redefining what exactly is meant by resuscitation within an acute hospital setting, extending its boundaries for research and recommendations to meet the needs of the seriously ill before they actually have a cardiac arrest or die.

The story of how to manage cardiac arrests in the community is slightly different. It must be very expensive to train so many in our society to perform CPR, although many of those trained and those providing the training are volunteers. Many cardiac arrests where CPR is attempted are sudden – young victims resuscitated after a sudden heart attack or a child rescued from a swimming pool – and this probably makes widespread community educational programs worthwhile.

It may be that hospitals will soon abandon the cardiac arrest team altogether, and develop a system whereby the right skills and experience are provided to the right patients at the right time. Whatever this system is, the response will also be able to deliver CPR in the rare case in which a cardiac arrest suddenly occurs without any of the usual warning signs.

Just as importantly, we need to identify those patients for whom deterioration and arrest is part of a natural end-of-life process; where medicine has nothing left to offer. While palliative care is well developed for patients with cancer, it is less common for patients dying of other untreatable diseases. The reasons for the reluctance of doctors to be more honest and transparent about the end of life are complex. Many calls for CPR are to patients where further active treatment would be futile. The cardiac arrest teams become surrogates for making decisions about whether further treatment is warranted. This is obviously unfair for a team that may not have encountered the patient before. Because they haven’t enough information at the time, futile CPR may be performed and admission to the intensive care unit may even follow to further prolong “life.”

HOSPITAL DOCTORS are notoriously reluctant to admit that there is nothing more that can be offered in terms of improving a patient’s medical condition – either to the patient or to themselves. Consequently, euphemisms have been developed by cardiac arrest teams, often together with the attending nursing staff, in a sort of conspiracy of inevitability. It’s frequently obvious to junior doctors and attending nursing staff that certain patients are just plain dying, but it is unwritten law that these matters may not be discussed with the specialist in charge. Instead, various codes have been developed in the event of a cardiac arrest call to these patients: a “show” code; “slow” code, or “ Hollywood” code are some of the words used to identify these “walk, don’t run” patients. Various cryptic initials or purple dots have been used to identify patients for whom not only CPR but any further active treatment would be futile.

Just over twenty years ago, a small step in the right direction was taken with the introduction of “Do not resuscitate,” or DNR, and “Not for resuscitation,” or NFR, orders. There is, however, a most glaring oversight here – if CPR rarely works in the terminally ill, why pretend that not delivering it makes any difference: the DNR order, in many cases, may be superfluous and unnecessary. At most, it’s probably a way of beginning discussions around end-of-life issues.

Intensive care staff know that patients rarely die suddenly when they are being monitored and supported with machines and drugs. They gradually fade away when the last vestiges of life have disappeared, usually in a predictable and orchestrated way. This is not usually the case on general wards, where often the prospect of dying naturally has not been discussed. CPR is a barely successful technique in hospital patients at the best of times, but in the terminally ill it is almost universally futile. And yet the designation of a DNR order is carried out with great solemnity and seriousness. Special forms are filled out and long discussions are held with patients, or if they are otherwise incompetent, with next-of-kin. Such is the power of the myth around CPR that physicians rarely admit to themselves, or to patients and their relatives, that what we are discussing is dying.

Armed with knowledge about the poor success rates of CPR and the lack of clarity around DNR orders, we should examine medical guidelines and the way the media portrays the issues. Doctors have been accused of being paternalistic and authoritarian by withholding potentially life-saving CPR. While doctors can, of course, be paternalistic and authoritarian, what they are doing with regard to DNR orders is almost the opposite and equally indefensible. Far from being paternalistic, the doctors are being naïve and ill-informed. They are, in most cases, continuing active treatment in the face of futility; with little self-insight, let alone being honest with the patients and their relatives. They are mindlessly sustaining life, as opposed to prematurely ending it. Nevertheless, the charge of inadequate discussion with patients and relatives stands.

In order to make sense of these media reports, it is crucial to differentiate between DNR orders and withholding and withdrawing active treatment. The first is really a non-order, whereas the latter addresses the real issues around end-of-life care. One cannot blame the media for not reporting these issues accurately, when policies around DNR are embedded in most hospitals around the world. For example, many policies have a statement along the lines of: “In the absence of a clearly recorded DNR order, the presumption must be that full resuscitation should be attempted.” In the defence of medicine, the acronym DNR has been replaced by DNAR (Do not attempt resuscitation), which may be a small step in acknowledging that any attempts are unlikely to be successful. There may, of course, be rare cases of accidental drug administration or other such misadventure, where resuscitation would, of course, be indicated and successful.

The need for CPR in a hospital is often a marker of serious and systemic problems in the hospital. Many cardiac arrests could have been potentially prevented altogether with an appropriate early detection and response system. The life of the young pillion passenger, Susan, could have been saved had we had such a system in place. Her tragedy has since led to rapid response systems to deteriorating patients being implemented in many parts of the world. •