TONY BENN hobbles onto the platform and selects the nearest chair, to a hum of comradely recognition from audience and fellow notables. Even after four decades the British left’s talisman can bring a touch of stardust to a routine political assembly. As he sits patiently through the chainsaw speeches, it’s not clear how far he is headline act and how far adornment. Invited to the spotlight at last, he rises to the billing.

Frail the eighty-seven-year-old former Labour MP may be, but the voice is lucid and steady as he veers from purpose (“what we are doing tonight is part of a national educational program which will go on until the political situation changes”) through protest (“the government is reopening battles we have fought and won over many centuries”) to principle (“the issue all over the world is one of democratic rights, and that underpins everything we do”) and the personal (“I’m more encouraged to go into the battle now than at any time in my life”). Five minutes in, experience and sheer life-force doing the work of once effortless command, he pauses; a sustained burst of applause finds itself quenching the flow. There’s a palpable release among the gathering of 200 people, evoking the kabuki audience’s cry at a dramatic climax: Mattemashita! We waited for this!

The occasion, in June 2012, was a London rally of the Coalition of Resistance, one of the many movements created in Britain since 2010 that aspired to unite the far left and take the fight to the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition. Everything about its choreography was comfortingly familiar: the leafleters and paper-wallahs from a dozen factions outside the venue (the lovely Friends’ Meeting House on Euston Road), the agitprop banners and placards, the cover-every-base list of speakers, the embalmed rhetoric, the conformist aura. But to Tony Benn there was nothing mundane here; each such meeting was part of an urgent, elevating, many-sided political campaign, one diary-packed day after another, pursued unswervingly across the second half of his life.

It was a late echo of how he had spent so much of those years: deploying sublime rhetorical skills to advance a case, mesmerise an audience, and solicit assent and acclaim. Whether at a Hyde Park or Trafalgar Square demonstration, Levellers or Tolpuddle anniversary, constituency club or trade-union fundraiser – or a book promotion, middle-England roadshow, student teach-in or BBC panel – give him a stage, an audience, a microphone and a cause; witness that golden voice, cultivated aura, crystal enunciation, majestic shift of register and shaft of humour; feel him disarm minds, lift hearts and carry true believers to a higher pitch of fervour. No one could perform like Tony Benn.

TONY BENN died at the age of eighty-eight on 14 March. The modern formalities – tributes from current leaders and former colleagues, TV and radio documentaries, respectful newspaper obituaries, a columnar waterfall, a Twitter deluge – instantly kicked in. The establishment also embraced its wayward son. The Queen granted his body an overnight rest in Westminster palace, an honour first bestowed on Margaret Thatcher; the speaker of the House of Commons allocated time to members (who include his son Hilary, also a Labour MP and minister) to pay respects. Benn had already become only the second, after Winston Churchill, to be awarded the “Freedom of the House.” (No one invents traditions, and with such unobtrusive swiftness, as Britain’s permanent inner state.)

A media and establishment event, then, but also a demotic one. For it was striking that so many people who had met, heard, read or worked with him were moved to personal eulogy, memoir, anecdote or citation. The intimate flavour of this reaction – even when laced with criticism, and there was plenty – is a measure of Benn’s singular presence in Britain’s public arena over many decades.

For a moment, several currents joined: those who had admired his prolific artistry as a communicator, supported his moralistic political message, respected his later constancy, witnessed his graciousness, or recalled the intense emotions he aroused. It was a reminder not just of his longevity but also of how deeply he had embedded himself in the public consciousness.

Benn’s funeral on 27 March brought all strands together. The media binge following his death had reminded some critics of the sentimentalism occasioned by Princess Diana’s in 1997. It also raised immediate echoes of the response to Margaret Thatcher’s death a year earlier, although the gruesome expressions of personal hatred that had attended the latter were absent. But the occasion, at a church next to parliament, had a flavour of its own. Outside, crowds of supporters sported flags and banners of his favourite causes. Inside, the ceremony included loving tributes from his children, renditions of William Blake’s “Jerusalem” and the Labour hymn “The Red Flag,” and an eclectic congregation: former Labour colleagues, but also Tory MPs and TV comics, Irish republicans and trade unionists, actors and authors.

This breadth of response is even more striking given that the outline of Benn’s political career suggests an almost banal story of high ambition in which reach exceeded grasp: fifty years as a Labour MP until retirement in 2001, four mid-level ministerial posts in the 1960s and 1970s, bids for the party leadership in 1976 and 1988 that ended in round defeat, and another two for the deputy leadership in 1971 and 1981, the latter failing by a hair of Denis Healey’s eyebrow. With such modest achievements and thwarted aims, how did he acquire such renown? And what, exactly, did it all amount to? Who, in fact, was “Tony Benn”?

THOSE references to “four decades” and “the second half of his life” are as good a route as any to an answer. For, in the 1970s, Benn’s thinking and direction took a radical turn. The mid-career shift was gradual and (like everything else in Benn’s life) came to acquire a mythologising glow that rendered it impermeable; but it was experienced as a profound conversion – and, in the spirit of the age, as one both political and personal. Its transformative effects would elevate him, not to the party and government leadership he craved, but to the role of proponent-in-chief of the syndicalist-state socialism that he regarded as the answer to Britain’s problems.

In the years before and after Margaret Thatcher’s counter-revolution took hold, Benn sought – both in government and in opposition – to mobilise new allies in the party and the trade unions behind a quasi-revolutionary crusade: nationalisation of large industries, state-backed workers’ control in industry, confiscatory tax policies, and a socialist foreign policy (including exit from Europe, NATO and the transatlantic alliance) that would end Britain’s position as “the last colony left in the British Empire.” Among an energetic left with political, industrial and academic strands, he was the chief figurehead of this ambitious agenda. The program was intertwined with his leadership hopes, for only Benn had the public standing and communicative skills to make it look tenable. He was never able, however, to secure majority support for it in the Labour Party as a whole, nor among more than a committed minority of the public.

Benn’s political trajectory in these years operated as a magnetic force. The mainstream politician with a reputation as a technocratic go-getter became the lodestar of Labour’s left, and a figure of fascination to the supportive “extra-parliamentary” left and intellectuals alike. (Ralph Miliband, father of Labour’s current leader, was one.) He also became a target of visceral and high-volume loathing from right-wing newspapers, and clumsy invigilation by the security agencies. These sentiments, in the neuralgic 1970s, reflected fear among a middle class rendered vulnerable by high inflation, rising working-class confidence, and a sense of national drift.

Thatcher’s victory in 1979 was this middle-class reaction made flesh. But her government was able to reverse the wider left’s momentum only after convulsive struggles in which luck and good timing as well as superior force and greater popular backing played their part.

Both Thatcher and Benn were politicians. They were also, at a time of crisis, standard bearers of incompatible diagnoses of Britain’s present and visions of its future. The stark ideological nature of the contest – at the time something new in British politics – suggests that theirs can plausibly be considered the defining rivalry in post-1945 British politics.

True, the rhythms of this right–left rivalry were always uneven. Benn never led or bestrode the Labour Party as Thatcher did the Conservative, and their careers didn’t align despite sharing a birth year, 1925. The exigencies of high office tended to moderate Thatcher’s instincts, while the ever-refined purity of opposition exerted on Benn no such discipline. There were to be no memorable parliamentary encounters across the despatch box; in fact, for most of his career Benn spent far more time denouncing Labour’s own leaders than he ever did senior Tories (with many of whom his relations were more than cordial).

In practice, the Thatcher–Benn divergence was absolute. Yet there was much convergence too. In their fervent doctrinal commitment, which put them at odds with the milk-and-water pragmatism (they would also say defeatism) of Britain’s postwar elite; their hostility to Europe’s “centralised bureaucracy”; their conviction that Britain’s economic model needed not tinkering but wholesale renovation; their insurgent challenge to respective party orthodoxies, which fed cultivation of fringe allies and intellectual outriders; even their sense of belonging to an international movement with global reverberations (which in the 1980s meant peace-and-socialism in Benn’s case and anti-communism-and-market-liberalism in Thatcher’s).

Benn did draw on his unmatched reserves of scorn to excoriate Thatcher during the terrible coal miners’ strike of 1984–85, the era’s pivotal domestic event (“a brutal woman following a politics of barbarism”). But the journalist Hugo Young records him in mid 1978 “[relishing] the disturbance Mrs Thatcher causes the establishment,” while sensing “that Whitehall does not want her to win.” His later mantra was to praise her as a “great teacher” of true purpose, “a signpost not a weathervane” who “just had a clear idea and followed it through.” If the compliments are self-serving, at a deeper level they also suggest – to put it in reductive English class terms – the toff’s forelock-tug to the grocer’s daughter, that she not he proved the effective anti-establishment radical.

THE IMAGE is less gratuitous than it may appear, for the Tony Benn story is also pervaded by class: its power realities, codes and associations, relationships and mental structures. True, that makes it resemble pretty much everything in Britain. But Benn’s is a singular case, and the sociological lens – as much or even more than the ideological – provides focus.

Behind his midlife conversion, after all, lay an upbringing in a very particular segment of Britain’s elite: the “great political family,” whose present-day incarnations can trace their affinity with liberal or conservative causes to the historic Whig–Tory divide or one of its many tributaries. Anthony Wedgwood Benn (for it is he) was the scion of a distinguished line: his two grandfathers and his father were Liberal MPs, the latter switching to Labour in 1928 and serving in two governments, including as minister for aviation in 1945–46. William Wedgwood Benn, who served as an airman in both world wars, was granted a (hereditary) peerage in 1942, which reverted to his younger son Anthony on his death in 1960. (His elder son Michael was killed in 1944.)

The young Anthony was therefore steeped in politics and, through his mother, religion. Margaret Holmes, born in Paisley in Scotland’s industrial west, became a scholar of theology and a leading figure in various Congregationalist churches (and eventually the first woman ordained as a bishop in Britain). If Anthony’s father introduced him in early childhood to such luminaries as Lloyd George, Mahatma Gandhi and Paul Robeson, his mother – a compulsive global traveller in her own right – gave him a code to live by. He often recalled her preference for the Old Testament prophets who preached justice over the kings who wielded power, and her favourite verse began Dare to be a Daniel / dare to stand alone.

After wartime service in the airforce and an Oxford degree, Anthony secured a candidacy in Bristol, a major city in England’s southwest, partly through the efforts of his former tutor Anthony Crosland (whose The Future of Socialism, published in 1956, would become a seminal work). He became an MP in 1951, in the election that ushered Clement Attlee’s reforming postwar government out of office, and acquired an early reputation as a coming man: appointed in 1956 to Hugh Gaitskell’s shadow cabinet (which he left two years later over the decision to retain nuclear weapons), but also noted for his assured, cut-glass contributions on BBC Radio’s Any Questions? panel. The media profile rose with his slick presentation of Labour’s television broadcasts in the 1959 election. (Labour’s third consecutive defeat was a moment of real angst in the party over its and society’s direction. Was affluence eroding socialism at its very roots?) The following year, however, faced Anthony Wedgwood Benn with a more immediate cause, one that lasted three years and propelled him into constitutional history.

William Wedgwood Benn, Lord Stansgate, died in 1960, automatically making Anthony a viscount who would qualify for a seat in the House of Lords – and, by the logic of his title – be denied the right to continue as an MP. It was a fate he had long been aware of; throughout the 1950s, he had been corresponding with authorities about the issue. (Anthony’s sibilant “ishoo” would later, via not unsympathetic media mockery, make the word his own.) A three-year legal battle against establishment archaism ensued, with Wedgwood Benn claiming the right to renounce his unwanted title and continue to represent his constituents. (“To be elected as an MP is the greatest honour open to any Englishman,” he said at the time.)

The battle’s highlights were two Bristol by-elections, both of which he won: the first to confirm local sentiment and embarrass the naysayers into change (even his Conservative opponent, absurdly taking the seat by default, was sympathetic), the second after eventual legal vindication, in a vote that allowed his return to a House of Commons from which he should never have been excluded. The bond between MP and constituents – in the very city where Edmund Burke had memorably addressed his electors on the subject in 1774 – was never so close.

The legislation permitting Wedgwood Benn to abandon his viscountcy (whose name, Stansgate, derives from the family seat in Essex, east of London) was passed in 1963. The reforged union with Bristol South East was timely, for Labour at last edged into office in 1964 under Harold Wilson, who then led the party to a sweeping majority in 1966. Wedgwood Benn moved smoothly into government: after a stint as postmaster-general (where his attempt to introduce a set of stamps shorn of the Queen’s head was thwarted by an old-school stitch-up) he reached the cabinet as minister of technology, becoming a vigorous proponent of state-backed “rationalisation” of carmaking and support for the fledgling computer industry.

By the mid sixties, “Wedgie” or “Wedgie Benn” was an intriguing blend. The combination of progressive background, classical education, egalitarian instincts and his own energetic futurism seemed a good match for a more fluid age. He had retraced the political path of his distinguished forebears; repudiated the hereditary principle in favour of elective democracy, challenging the old order with its own tools; and emerged as a modern personality, at home in the world of broadcasting and at ease with people in a society moving beyond constriction and deference. He was going places.

SEVERAL factors came together to push Wedgwood Benn in a new direction. The generational revolt of 1968 was one; a Fabian pamphlet he wrote soon after argued that conventional politics had to respond to demands for greater participation and accountability. Labour’s shock defeat to Edward Heath’s Conservatives in 1970 was another, revealing a party more bedraggled and uncertain than it knew. But the new Tory government soon faced a barrage of strikes, not least from the powerful miners’ union, and as shadow industry secretary Wedgwood Benn was pitched into the fray. With confident expectation of a quick return to government, he drew up sweeping plans for co-management and workers’ control of existing and new enterprises. With Labour’s narrow wins in 1974, the year of two elections, Wedgwood Benn relished an interventionist stint as industry minister: forming cooperatives, bailing out companies, above all mixing with workers.

Britain’s accession to the European Economic Community in 1973 gave him another high-profile cause. Labour was deeply split on the matter, and Wedgwood Benn’s proposal that the next Labour government should hold a plebiscite on membership acted as temporary adhesive. The unprecedented pan-UK referendum on Europe in 1975 was Wedgwood Benn’s second constitutional innovation. The campaign was a foretaste of later cross-party alliances and schisms, not least in its suspension of “collective cabinet responsibility” for the duration. It ended in a decisive win for the pro-Europe side (led by Thatcher, in her early months as Tory leader, with business almost wholly supportive); but Wedgwood Benn’s passionate speeches against the “capitalist club,” strongly backed by most unions and many Labour members, reinforced his emerging status as the left’s darling.

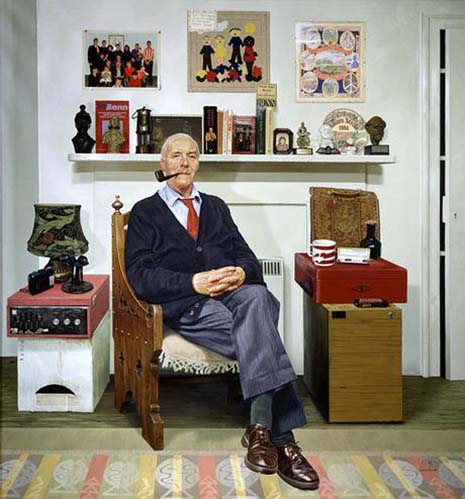

There was a further aspect to the post-1970 turn. Anthony Wedgwood Benn’s entry in the annual Who’s Who compendium was successively trimmed of surplus credentials, including his education at Westminster, a top public school (which, this being England, means a private school). This and the adoption of “Tony Benn” seemed a symbolic counterpart of his political journey, with Benn discarding the accoutrements of his elite background and acquiring more fitting proletarian ones (pipe, tea-mug, satchel, experimental headgear, demotic “y’know” and other verbal tics). Indeed, Benn’s encounter with the working class in this period has a definite anthropological flavour, recalling late-Victorian expeditions to London’s East End by missionaries of the high-minded middle class – with a transcendent impulse to save souls, break chains, heal bodies, free minds, plan strikes, or win votes.

Benn had in fact always smoked a pipe, but the insistence in the way the props were deployed – plus a certain élan that evoked Charlie Chaplin with bowler and umbrella – quickly made them a trademark. Cartoonists were joyful and their editors gleeful at the gift of what would become decades of work and ridicule. But if some Labour colleagues were bemused at the stylistic makeover – the affectionate, sardonic portrayal of Benn in this period is a highlight of Susan Crosland’s lovely memoir of Tony Crosland – the growing exhibitionism of his politics was a source of real exasperation.

THE LABOUR government of 1974–79 spent its life buffeted by economic turbulence against a febrile background of industrial conflict, the Northern Ireland war, social tensions and seductive extremisms. It struggled to keep going on a tiny majority that was leaching away in by-elections and defections. Emergency became a way of life, the most serious being the International Monetary Fund loan crisis of 1976 and the wave of public-sector strikes in 1978–79. There was something heroic in its survival. But the experience was cauterising, and the party slouched towards the election with fear in its heart. This time the widespread expectation was less of an early return to office than of a divisive inquest, bitter leadership contest, and years in opposition.

Tony Benn had lasted only a turbulent year as industry minister before Harold Wilson, the prime minister, transferred him to energy after the Europe referendum; in effect it was a demotion, but allowed Benn to oversee the oil industry in its early North Sea boom years. He had tried for the party leadership when Wilson suddenly resigned in 1976, but dropped out after coming fourth of six candidates in the first ballot, leaving James Callaghan to defeat Michael Foot and Denis Healey. Under Labour’s rules at the time, only MPs voted for the leader (which meant they were also choosing a prime minister). Everyone knew that Benn would try again after the party’s defeat, though his base of parliamentary support would likely remain too thin to take him to victory. Benn and his followers had an answer to that dilemma: change the rules.

Margaret Thatcher’s triumph in the 1979 election was a vote against drift and division, if not precisely for a new course. Most on the left – with honourable exceptions such as the sociologist Stuart Hall – had long regarded the opposition leader as dangerous but not serious. (Benn himself saw Labour’s ejection as “a surrender rather than a defeat,” revealing the bankruptcy of “non-political trade unionism” and “non-socialist Labourism.”) By 1981 a wrenching recession and the new government’s unpopularity was doing nothing to stay the widespread conviction that the forward march of history had taken a mere detour. But history needed guidance to reach its destination. The Wilson–Callaghan governments showed this: they had ignored manifesto pledges, abandoned Labour members and betrayed socialism. The prescription was to gain control of the party machine, then the leadership, in order to ensure that next time was different. “I don’t accept that democracy is just a matter of style, it’s a matter of who is accountable to who,” Benn said in 1980.

For the “Bennites,” a core element of the drive to transform Labour’s internal structures was extending the franchise in party leadership elections. The aim was consistent with the idea that Benn had championed for a decade, of enriching democracy via more participation, and promised to mobilise the grassroots and union support he had cultivated. This mix of principle and calculation, however, meant the reform became a factor in the party’s acrimonious divisions. These erupted at a special conference in January 1981, three months after Michael Foot had succeeded Callaghan as leader. By this stage Benn had majority support on the party’s national executive and key sub-committees, reflected in a decision to give Labour MPs, unions and members a forty-thirty-thirty percentage of votes.

This was the zenith of Tony Benn’s career. It was also a moment of intoxication. A measured response that sought to heal the scars of months of conflict was beyond him: instead, his acidic victory speech foreshadowed a campaign for the deputy leadership, evidently with more to come. This ensured the contest, and the manic sectarian furies now released, would dominate the year. More immediately, the conference result provoked the departure of several leading figures on Labour’s right, who would become the nucleus of the Social Democratic Party, or SDP.

Inside the party, civil war raged. Most Bennites were Labour loyalists, part of a mainstream left that had always existed and were looking for a more radical direction. After many disappointments, and in the disorienting early Thatcher years, they saw Benn as the best chance of making the party more democratic, more socialist, and more successful.

There were others for whom the high tide of “Bennery” or “Bennism” (other items in an expanding political lexicon) was a platform to greater power. These were the cadres of the “Militant tendency,” a Trotskyist cult, which for years had worked to take advantage of Labour’s federative structure by establishing control of often moribund constituency parties and other affiliated groups, then burrowing upwards. Militant’s “entryism,” or infiltration, was systematic; its ideology, mechanistic; its discipline, zealous; its secrecy, absolute; its mindset, doctrinaire; its publications, unrelieved; its personality, dour and charmless. Even by the unlovely standards of Britain’s far left, Militant was a real piece of work.

Few of Tony Benn’s new adherents belonged to Militant (which referred to him as “Kerensky” to its Lenin); more were associated with other far-left groups. But there was mutual advantage in keeping distance. Benn’s indulgence was unswerving, a guarantee of useful cover to those concealing their true affiliation. In turn he received the benefit of their resources and personnel.

The deputy leadership campaign of 1981 was the apogee of this alliance. It had the atmosphere more of a crusade than an election, and was distinguished by a strain of genuine fanaticism. These elements – which Benn did much to rouse and little to douse – made it a rare and memorable event in British party politics.

In a poisonous climate, the left imploded. An emergent Labour “soft left” broke painfully with Benn and the “hard left” as, one by one, his former satraps were mugged by reality. The left’s schism allowed Denis Healey, former defence secretary and chancellor, to defeat Benn and remain Michael Foot’s deputy. The new election rules that Benn had pioneered – his third great contribution to British democracy, it could be said – had, in the end, not been enough.

THE FAILURE to win Labour’s deputy leadership in September 1981 was in effect the end of Tony Benn’s political career, though the forces released during his ascent and the corrosive legacy of the period meant this was fully apparent only in retrospect. Benn continued to be a major player within the party, as chair of its powerful home policy committee. Militant continued to grow and place its members in party positions (in 1987 it increased its contingent of MPs from two to three). But after the 1981 catharsis there was now a counterweight to the Bennite insurgency. The party launched internal inquiries into Militant’s activities, inevitably lengthy given the legal complications and the stout resistance from a still well-placed “hard left.” There were some expulsions. The cost – administrative, financial-legal, political and human – was huge. The 1980s were in every sense a lost decade.

Labour’s lowest point was the 1983 election, when Thatcher’s Conservatives won a sweeping victory and the SDP (in alliance with the Liberals) ran Labour close for second place; the party received 27.6 per cent of the votes, the smallest proportion since 1922. An unwieldy manifesto full of impossibilist pledges was a gift to the Tories, who brandished it with sadistic delight at every opportunity (“the longest suicide-note in history,” a Labour insider called it – probably Peter Shore, a leadership candidate in the aftermath). The campaign was a shambles. By then, Thatcher had something to defend (notably council-house sales), and the recovery of the Falkland Islands from Argentina had burnished her patriotic credentials. But it was clear that the people were also casting a verdict on Labour’s years of civil war.

Tony Benn obliquely acknowledged it. “[The] inward-looking nature of the Party has done us down,” he told his diary. But in public, as ever, he put on a good show. Ten days after the vote, he told the Guardian: “The general election of 1983 has produced one important result that has passed virtually without comment in the media. It is that, for the first time since 1945, a political party with an openly socialist policy has received the support of over eight and a half million people.”

Benn had contested the new Bristol East constituency after a redrawing of boundaries, and lost. This meant he could not take part in the post-election leadership contest which saw Michael Foot succeeded by his protégé, the “soft left” Neil Kinnock. In March 1984 he was back in parliament after winning a by-election in the market town of Chesterfield, whose proximity to the central English coalfields embroiled it in the coal miners’ strike that erupted days later in protest against plans to close “uneconomic” pits. The dispute became, partly by misfortune, an implacable class and political struggle that lasted a year. Benn gave unqualified support to the striking miners (three-quarters of the total) and their messianic union leader, Arthur Scargill, whose explicitly insurrectionist aims and inflexible strategy left no space for manoeuvre. The miners’ unequal contest against a ruthless state operation broke hearts and divided minds across the land. In political terms it sealed Thatcherism’s ascendancy, but also the end of the post-1945 social settlement. The forward march of history, it turned out, had another direction entirely in mind.

IN THE LATE 1980s, while the party’s leadership sought a return ticket from the abyss, the left huddled together in a cold climate and in the process rewarmed Benn’s own ambitions. The Bennite fragments made his new constituency a revivalist hub. The Chesterfield Conferences, the Socialist Society, the Independent Left Corresponding Society – the town’s famously crooked church spire looked down benignly on them all. This was also a period when Benn’s instrumental embrace of English strands of radical dissent was, in conscious opposition to Thatcherism’s appropriation of the national past, nurturing an incipient socialist heritage industry. (“Ancestor worship,” the historian Raphael Samuel called the approach in a 1984 review. Samuel notes that Benn’s grasp of tradition “is essentially additive: new causes are given their historical lineage as they loom on the contemporary horizon” while “the old ones stay unchanged.”)

A year after Thatcher’s third election victory in 1987, when Labour increased its vote only to 30.8 per cent, Benn challenged Kinnock for the party leadership. It was a decision that even some in his diminished coterie found quixotic. Benn received 11.4 per cent under the electoral college system he had secured, almost the same proportion of the vote delivered to him by the MPs-only electorate in 1976.

The accelerating dramas of British and world politics in the late 1980s and beyond were hard for the Bennites. Now it was others who were making history and claiming the future. Benn had an honourable record as an anti-colonialist and opponent of apartheid, and was (in his words) “a United Nations man,” but – on the same all-to-the-left-are-friends principle that governed his attitude to Militant – he had no imaginative grasp of communism and no sense of Soviet-bloc history or affinity with its countries’ victims and dissidents. The end of the Soviet Union was a cause only of regret. He was a “great admirer” of Mao Zedong, he records himself telling a Chinese diplomat in 1996: “He made mistakes, because everybody does, but it seems to me that the development of the countryside and so on was very sensible…”

Benn wasn’t interested enough in communism or other non-Western dictatorships to be a “fellow traveller,” rather his overriding political anathemas (the British establishment, Labour Party leaderships, the European Union, NATO, and US administrations) allotted these systems a fixed place in his moral universe that precluded criticism. They existed for him only as victims or targets of the West, never as agents of violence on their own account. This combination of moral absolutism and moral exclusivism, which his great rhetorical gifts finessed, found Benn new and receptive audiences when be became a figurehead of campaigns opposed to all Britain’s “new wars,” actual and potential, from Kosovo in 1999 to Syria in 2013.

By then, the domestic landscape had been further transformed. The convivial Scots lawyer John Smith had succeeded Kinnock after Labour’s fourth election defeat in 1992 (this time to Thatcher’s replacement, John Major). Smith’s sudden death in 1994 opened the way towards “New Labour,” at that stage jointly parented by Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The landslide win of 1997, ending eighteen years of Tory rule, was secured on the promise of change that respected the fundamentals of the economic model created under Thatcher. Benn, by now in his early seventies, was ever despairing and ever contemptuous of New Labour’s accommodation with reality. To the end, he was incapable of any reckoning with his own role in making it necessary.

AN EARLY PROMISE not to contest the 2001 election left him uneasy about the future. Politics and the burning ambition to be at “the centre of things” had been his life. What could he do, who would he be, without it?

In the event, Caroline Benn – his wife of fifty years, an educationalist and unstinting ally – provided the script that would turn a difficult transition into a late flourishing. As he wondered how he would present the decision, she suggested: “Why don’t you say you are giving up parliament to devote more time to politics?”

Caroline’s death in 2000 was a dreadful blow, but her words were a precious legacy. For they became an endlessly quoted formula, both reflecting and reinforcing Benn’s outsiderish appeal in an age when trust in official politics was receding and bubbling political energies were seeking fresh creative channels. The last dozen years of Benn’s life would be full of such obliging collisions between life and zeitgeist that would cast over his persona a glow of almost mystical benevolence. The others included an avid interest in celebrities, an explosion of media outlets and technologies, and, echoing demographic and cultural trends, a nostalgia boom.

In practice, “more time for politics” meant that Benn’s extra-parliamentary life was indeed as packed as what went before. It started uncertainly, but soon became a non-stop carousel, as he extended his repertoire into an ever wider range of formats: myriad anti-war meetings and marches (especially after 9/11 and before and during the invasion of Iraq in 2003); an annual Pied Piper slot at the giant Glastonbury music festival (where the “Left Field” attempted to add a political edge to a gentrifying occasion); frequent tours on the folk circuit with the musician Roy Bailey, where Benn would declaim extracts from their Writings on the Wall, “a radical and socialist anthology 1215–1984”; a column in the Morning Star; regular theatre tours of his An Evening with Tony Benn, an ambient dialogue with third-age admirers, often in conservative locations; gatherings at Burford or Putney or Peterloo to commemorate great popular struggles of past centuries; and endless events at book promotions and literary festivals to talk about his diaries, democracy, war, Labour’s betrayals.

Whatever the occasion or cause, however, the true purpose of every appearance in the post-2001 years soon morphed from “more time for politics” to “being Tony Benn.” In the course of it all, he found ever widening circles of, not exactly followers, but new admirers, devotees, even fans: from twenty-somethings who cheered his impeccable disdain for unjust wars, corrupt politics and out-of-touch parties, to fifty-somethings upwards who basked in the same laments, in the latter case with a frisson at the reconnection with a shared past.

This late run in the limelight was an example of history’s cunning. Benn’s mid-career rebranding had, to many onlookers, always been a hard sell: the self-effacement too calculated, the sanctimony too suffocating, the connections with his purgative politics and rancorous acolytes too obvious. But time’s work, as so often in Britain, was to recharge this past in unexpected ways, drawing its political sting and leaving only the anti-political balm. Thus, in an outcome unimaginable when his toxic influence was at its height, did “Tony Benn” re-emerge after 2001 as yet another British invented tradition, one more form of ancestor worship.

WHAT, AT HEART, was going on in these late years? In time it will be for a properly critical biographer to connect this phase of his life with earlier ones. Here are five initial threads to pull.

In marketing terms, it turned out that Benn’s timing was perfect. He was familiar to people of several generations who were solvent, were interested in politics, and had cultural capital. He was a fluent and compelling speaker, and endlessly available. He had an assembly-line of hefty diaries and books of speeches or columns to sell, whose rich human interest – Benn knew and had a story about everyone – leavened the political bromides. He had a bottomless facility for parlaying any complex world problem into agreeable messages via humorous parables, each one polished as furiously as any Downton Abbey chandelier.

Indeed, the sociological aspect is unmissable. Benn’s father had sent him to public school so that he would “be able to take on the Tories.” In late life it enabled him to comfort them, too. The radiating patrician glow, the air of absolute assurance of his place in the natural social order, the beautiful cadences, the deft evasions, all honed by decades of public speaking: Tony Benn was in every sense a class act.

Britain loves a left-wing lord; it too covers every base. To the “movement” he was (in the words of the country’s most powerful trade-union leader) “a friend of the workers”; to the left-liberal tribe, he was “one of us”; to middle England, he was an upmarket salesman of pipe-and-slippers socialism, the sort that flows seamlessly into conservative melancholy over Britain’s decline, the default national attitude.

There’s also an anthropological quality, glimpsed in the profusion of accounts by journalists after Benn’s death of their visits to interview him. Their copy is eerily similar: the genial welcome to his Holland Park home, the iconic basement chaos of papers and mementoes, the hour’s chat and its familiar homilies (“If you file your wastepaper basket for fifty years, you build a public library”), the rueful references to his transition from “the most dangerous man in Britain” to “national treasure,” the warm farewell, the closing encomiums to his patience, charm and kindness. The ritual aspect is striking: in recollection, the audience with Tony Benn resembles more a receipt of blessings than a meeting with a senior politician.

But evidently, the religious dimension pervades Benn’s life as it shaped his being. He always had a touch of sanctimony (Richard Crossman, a cabinet colleague and fellow diarist, noted in 1968 that “he has at times a mechanical Nonconformist self-righteousness about him”) and this was to become ever more marked with the conversion. A role as righteous missionary of the new faith followed; a period as fundamentalist preacher, leading the Bennite cult to the promised land; then an extended role as a prophet, the voice in the wilderness still in possession of the holy grail of true socialism, but rejected by the unbelievers; finally as a revered sage, the benevolent keeper of the faith, dispensing ancient wisdom to young supplicants of what was now the Tony Benn cult.

There is, finally, the political lens. What those interviewers miss is how much Tony Benn needed them to come. His genius, after all, was to make people collude in the fantasy world he spun. But for that he had to have an audience. He had no other life than politician. He barely read a book, had no interest in literature or art or sport or music or history. He had failed in every major political endeavour (no intrinsic shame in that) and brought his party to catastrophe (plenty in that). His consuming ambition had hit a rock in 1981, but he could neither let go nor ever begin to understand the reasons; it was too painful ever to try, and would have required insight he didn’t possess.

But he still had those immense talents as a communicator. He retained his constituency and a loyal band, and continued to proselytise among the faithful, every claque feeding his impregnable self-regard. Then, in the unceasing campaign of the last years he found quasi-success of an unimagined kind: prime minister of his own little English republic, whose diverse citizens savoured their adulation of this figure who never challenged but always reflected back to them what they wanted to see, hear and feel. All the acclaim, however, could not satisfy him; he always wanted more, and the unexaminable past haunted him. He was trapped by the worshippers in love with the image he and they together had created. But this celebrity was also his life. Not an inch of space remained in which to move.

A SORT OF CONFESSION is buried in the diaries of his late years, published under a title chosen years before that bears no relation to their painful contents, A Blaze of Autumn Sunshine: “When I look back on my life, I’ve been so obsessed with myself all the time – Benn, Benn, Benn, Tony Benn – and actually I’m just not interesting… I fear that perhaps my diary and my archives are an attempt to prolong my life in some way.” This, after twenty million words in the diaries alone. But he couldn’t help himself. There is even a “legacy” video message made in 2002, intended (it is said) for his grandchildren, yet also broadcast posthumously on Channel 4, as well as a book of letters to them; and forthcoming is a sepia-drenched documentary film on his life, Will and Testament, whose director is quoted as saying that Benn was “very embarrassed” at the attention.

The faithful are happy to collude in the eternalisation as a way to secure his worldly afterlife. The Guardian’s lengthy editorial tribute concludes with a phrase that would be sinister were it not preposterous: Benn is “destined to be loved in popular memory for his defence of democracy and freedom.” By welcome contrast, a spoof diary by the brilliant Private Eye satirist Craig Brown, for many years a joyous and forensic critic of Benn’s pretensions, imagines him meeting the Almighty (“Out of common courtesy, I treat him as an equal… A media figure, really, when all is said and done. But perfectly pleasant, and clearly delighted to see me”).

The reverent media of the post-parliament years will keep the Tony Benn brand going, even if a crowded nostalgia market limits its purchase. In time it will be for a biographer to disentangle his political record and contributions from the alternative universe that he conjured. The twist is that Britain itself lives by creating fictions it chooses to believe in, which enable it to cope with reality. Tony Benn, the arch illusionist, can for the moment rest easy. •